Reviews

Agnes Pelton Went to the Desert in Search of Solace. Her Paintings at the Whitney Show She Found Something Magical There

A survey of the spiritual-abstractionist painter's oracular art brings an offbeat brand of enlightenment to New York.

A survey of the spiritual-abstractionist painter's oracular art brings an offbeat brand of enlightenment to New York.

Consider two paintings.

One is Mother of Silence (1933), by the early 20th century spiritual-abstractionist painter Agnes Pelton. She is the star of a show that has just arrived at the Whitney Museum, part of a wave of recent interest in experimental art by previously unsung or undersung female artists working in esoteric or occult traditions, a vogue that is currently rewriting how museums approach the history of modern art.

Mother of Silence centers on a cluster of numinous blobs in pale lavender, pink, and turquoise pastels, set off against a red and black background and wreathed by precisely organized whorls of energy. It suggests the form of a seated Buddha.

Installation view of Agnes Pelton, Mother of Silence at the Whitney. Image: Ben Davis.

Now consider a painting not in the show, Mother of the World (1924), by the Russian painter, set designer, adventurer, and mystic Nikolai Roerich. In rich tones and flattened perspective, it depicts the veiled figure of the ultimate female goddess in Roerich’s occult system, seated on her mountain throne and framed by divine halos.

Left to right: Agnes Pelton, Mother of Silence (1933) and Nicholas Roerich, Mother of the World (1924).

Look at the two together and you get a clear sense of the kind of archetypal image that Pelton is adumbrating in her abstraction. I have no idea if Pelton is referencing this exact image. However, she and her art both were deeply inspired by Agni Yoga, the doctrine that Roerich and his wife Helena dreamed up in the 1920s, claiming to be channeling Eastern wisdom through spiritual séances.

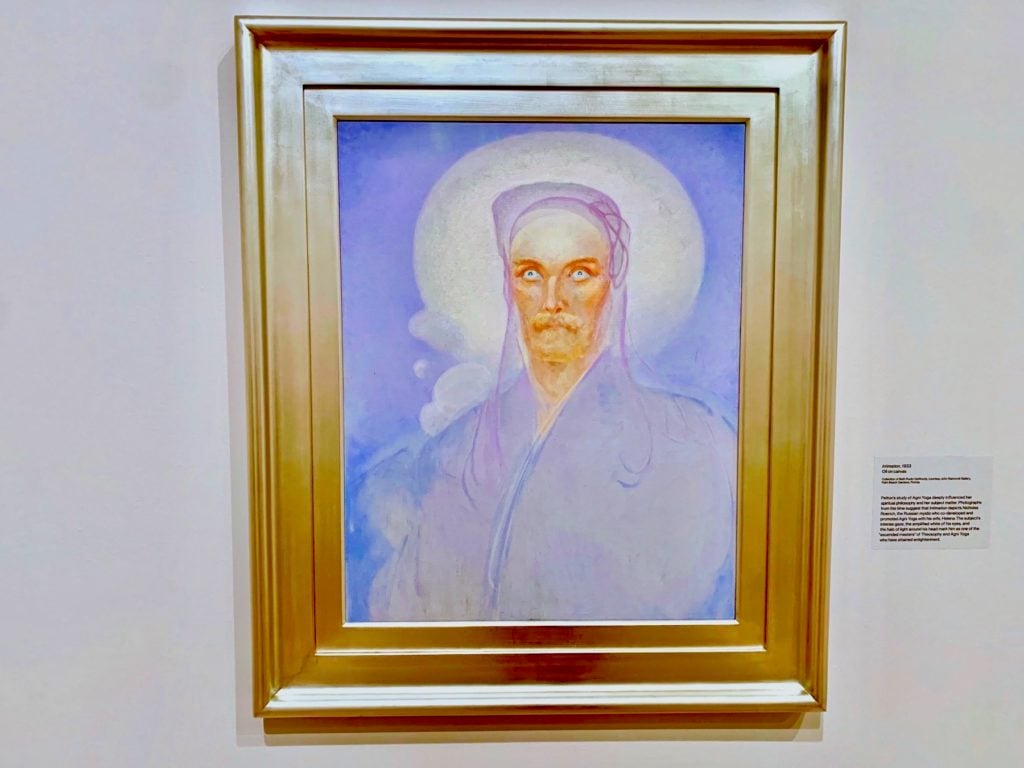

Indeed, one of the rare figurative works in the Whitney show—and a slightly unsettling beat in its otherwise serenely etherial atmosphere—is Intimation (1933). This is Pelton’s portrait of Nikolai Roerich, rendered in gauzy, unearthly colors and full guru style, his beady-eyed gaze transfixing the viewer.

Agnes Pelton, Intimation (1933). Image: Ben Davis.

“Agni Yoga” meant “Path to the Divine Fire.” The Roerichs’ doctrine celebrated fire as the symbol of the energy animating all fixed things and all forms of wisdom, “the essence of the entire life, all-embracing, evading nought.” The veiled goddess-of-goddesses shown in Nikolai’s painting was conceived as his ultimate unifying symbol of the divine light, whose energy, he preached, would be at last unveiled when the coming “Age of Fire” dawned. Then, as the Handbook of the Theosophical Current explains, “fiery energies will move toward the sphere of the Earth to purify it from a surrounding heavy atmosphere caused by the crimes committed by humans.”

In any case, the comparison merits two linked comments, one formal, one symbolic.

Formally, Roarich’s painting clearly draws on Russian orthodox icon depictions of the Virgin, given a fanciful Buddhist-accented makeover. This mash-up makes sense, since Agni Yoga’s ideas were syncretic, promising to reveal the common secret wisdom at the root of all religions. Pictorially, however, it takes us towards devotional cliché.

The modernist vortex of Pelton’s Mother of Silence, on the other hand, makes for a quietly more awesome spin on the subject.

And consequently, Pelton’s Mother better fits what I take to be both works’ underlying idea: a spiritual presence who incarnates the protean energy at the root of all earthly things. The miasmic, dreamy character of the Pelton painting is far more evocative of that idea than the deliberately stiff, folk art style of the Roarich one.

The student surpasses the master here, or the acolyte outshines the guru.

Originally organized at the Phoenix Art Museum by Gilbert Vicario, “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” features 40-odd paintings by Pelton, of the only 100 or so abstractions she made during her life. She made figurative art too, tourist-friendly California landscapes (she actually called them “Tourist Paintings”) that she sold to support herself when money got tight, but none are here. Her more modernist works are what she considered to be her calling.

“Always do ‘this’ work first, others only when these do not call you,” Pelton advised herself in her diary, writing of the abstract-symbolic works. She arrived at their forms via extensive meditation and trance, transcribing into her notebook exact sketches of the seemingly aleatory constellations of forms and symbols that came to her before rendering them to canvas.

Agnes Pelton, Fires in Space (1938). Image: Ben Davis.

Without knowing anything about Agnes Pelton’s story, you would likely guess something about these paintings’ subject matter: solitude (because of their evocations of empty landscapes); healing (because of their gentle, nourishing color palette); and mysticism (because of their many occult symbols: evening stars, floating portals, roses, swans, lotus flowers, magic mountains, holy deserts, “windows of illumination” opening in space, and flares of the divine Roerichian fire breaking into reality).

Still, it’s worth knowing a bit about Pelton’s life story. Born in 1881, her life was vividly shaped by family events that happened before she was even born: 19th-century Brooklyn’s most infamous sex scandal, the Beecher–Tilton Affair. Her grandmother, Elizabeth Tilton, had been exposed as having an affair with liberal preacher Henry Ward Beecher. Her grandfather, once a Beecher acolyte, sued for “alienation of affection.” Doubling his humiliation, he lost in court, and was estranged from the church and from New York society.

Agnes Pelton, Orbits (1934). Image: Ben Davis.

Of her family’s heritance of infamy, Pelton would remember that “it cramped our whole life and it also cramped mine…. [it] overshadowed me.” Her mother (who had been the one to report the infidelity) married a wealthy but troubled man from a Louisiana sugar empire. He died of morphine overdose in 1891. Young Agnes grew up “inclined to melancholy and tears,” surrounded by “deeply religious and perhaps unnecessarily serious people.” She was diagnosed with “neurotic fever” at 19, and may have had an eating disorder.

Pelton would find comfort in two things. One was art, which she studied at Pratt starting as a teenager, going on to paint portraits for money, and Symbolist-inspired canvasses out of passion. She would show at the 1913 Armory Show, the sensational survey that introduced ideas of modern art to still-provincial USA (Marcel Duchamp’s Cubistic Nude Descending a Staircase was the big succès de scandale). There, Pelton’s work appeared alongside future heroes of the art history textbooks like Charles Sheeler and Marsden Hartley.

Agnes Pelton, Room Decoration in Purple and Gray (1917). Image: Ben Davis.

The Whitney’s show features just one introductory example that gives a taste of Pelton’s early mode of the 1910s, her “Imaginative Paintings.” It’s a large canvas—her largest, actually a painting for a mural—featuring a woman walking in a secluded garden landscape that has a swirling, animate character. It skirts Symbolist kitsch (her own later judgment on these early works, according to the show catalogue, is that they were “insincere” and “not real”).

Nevertheless, the idea of the solo female seeker in communion with natural and cosmic forces was the foundation of all the more experimental work Pelton did—though a theme she would elaborate in less and less literal ways.

Pelton’s other comfort was alternative spirituality. In the 1920s, in her 40s, her mother died and she left New York to live in a windmill house on Long Island. She also developed an interest in Theosophy, the epiphanic slurry of pan-religious beliefs pioneered by Russian émigré and occult entrepreneur Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891). It was under the influence of Theosophical ideas about accessing an abstract “Divine Reality” at the root of all perception that Pelton began her adventures into abstraction, such as the The Ray Supreme (1925) and Being (1926), which suggest physical reality shot through with spiritual vibrations.

Agnes Pelton, Being (1926). Image: Ben Davis.

Her best works, however, are from a little later. In 1930, through an acquaintance with composer and “transpersonal astrologer” Dane Rudhyar, Pelton would discover the Roerichs’ Agni Yoga doctrine, a heretical elaboration of Theosophy that, in addition to spinning pages of alluring hokum out of the transcultural significance of fire, stressed self-help and moral improvement through spiritual living.

The Roerichs’ tome, Leaves of Moyra’s Garden, advised the reader: “In creation realize the happiness of life, and unto the desert turn thine eye.” In 1932, Pelton complied literally, moving West to Cathedral City, California, near Desert Hot Springs, where she found the solitude in which she had always longed to work, as well as the community of others with similar esoteric interests.

Made after her arrival, a painting like Sand Storm can be read as allegorical of Pelton literally “turning her eye” to the desert to find happiness: The canvas shows a floriform window of divine light, piercing through the swirling clouds of desert sand, conjuring a hardy, healing rainbow.

Agnes Pelton, Sand Storm (1932). Image: Ben Davis.

How to look at these paintings, with their wonky, hieratic quality? Part of their appeal is their exotic sense of marshaling secret totems and magical signs, but a lot of their esoteric symbolism remains remote. I also think the search for a master code might miss the point of such imagery for Pelton herself.

Pelton’s family history had been scarred by the rigidity, coldness, dogma, and moral judgementalism of New York’s Gilded Age religious society. Aside from offering the spiritual warmth of a literal fire cult, proto-New Age philosophies like Agni Yoga appealed because they seemed a tool to free yourself from dogmatic constraints—they encouraged curiosity in the whole panoply of world religions, and you could take from them what you wanted, in a highly personal way.

Agnes Pelton, Resurgence (1938). Image: Ben Davis.

Pelton seems to have read deeply and widely in esoteric literature and forged her own synthesis to meet her own needs. As much as Mother of Silence evokes Roerich’s goddess of divine fire, for instance, it also seems to have been for the artist an avatar of her own mother’s spirit as well. In Pelton’s California studio, she kept the canvas near her, to commune with its spirit for advice on painting and to give her comfort in times of money woes.

What made esoteric philosophies so appealing to so many people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was how they triangulated between faith and freedom. They offered a sense of metaphysical order and higher truth appealing to those from religious backgrounds, but also promised a modern freedom from old doctrinal rigidities and the ability to make one’s own path. This delicate balance is coded into the formal texture and symbolic vocabulary of Pelton’s canvasses: Her art gives a comfortingly ordered, hieroglyphic form to symbols of protean, unbounded potential: holy fire (Mount of Flame, 1932), swelling oceans (Sea Change, 1931), rippling atmosphere (Red and Blue, 1938).

Agnes Pelton, Red and Blue (ca. 1938). Image: Ben Davis.

And what is true within the canvasses is also true between them: Pelton’s art embodies a protean spirit in that she never really repeats an idea.

Clearly, Pelton’s work has its own recognizable mix of abstract color-forms, allusions to landscape, and far-out symbolism. But each composition distinctly introduces a new pictorial idea—and you can’t help but think that the newness is part of the point, that what each work symbolizes, in its unique conjugation of forms, is being in touch with an energy that is ever-changing.

Agnes Pelton, Prelude (1943). Image: Ben Davis.

The point I would make is that her particular spiritual disposition is also an aesthetic asset. Pelton’s restlessly questing imperative is part of what makes her art a font of pleasant surprises. Just when you think you’ve got her style figured out, there appears something like Prelude (1943), with its saffron sky blossoming with floating gear shapes. Where’d that come from? It’s like a little revelation.

Perhaps you could argue that all this simply means that, as much as Agnes Pelton’s art answered a spiritual call and an inner necessity, she also was a trained artist and brought an artist’s instinct for formal freshness to her quiet desert studio.

Though she did not experience huge success in her lifetime, Pelton showed her spiritual-abstract works at such non-arcane institutions as the San Diego Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Crocker Art Museum, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. She certainly seemed to have believed that she was bringing into the world images with a higher significance, but unlike more mediumistically inspired artists who viewed themselves as mere vessels, Pelton signed her finished canvasses with her name, at the bottom corner, like someone who hoped to be recognized for her individual vision.

But there’s a reason to think that Pelton’s avoidance of repetition or working in series was more than just an artistic taste, a clue that continuous symbolic evolution was the lifeforce of her mode of creation in a particular way. Throughout the decades of her oeuvre as seen at the Whitney, she never repeats herself—except for once.

Agnes Pelton, Light Center (1947-48). Image: Ben Davis.

In 1947-48, Pelton made a work called Light Center, a hovering oval of energy suspended between an animate, rippling earth and a gauzy, serenely agitated sky.

Agnes Pelton, Light Center (1960-61). Image: Ben Davis.

In 1960-61, she repeated the same composition. Charcoal lines remain on the canvas, where you see her trying to plot how exactly to tweak the image to make it repeat. These lines remain on the work because she died before she finished it.

Who knows why Agnes Pelton turned, at that moment, to her own back catalogue for inspiration. In 1943, a friend, Jane Levington Comfort, had observed in a letter to a mutual acquaintance that Pelton “is very fragile and very potent—much more so than she knows anything about or would dream of believing if you told her.” And so it is a beautiful thought that this artist, who had all her life restlessly looked for wisdom from the beyond, was complete enough at the end to let herself take inspiration from her own power.

“Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, through September 1, 2020.