Art & Exhibitions

At Montreal Biennial Artists Tackle Sexual Politics In the 21st Century

"Sexting," "revenge porn," and "The Fappening" have cameos.

"Sexting," "revenge porn," and "The Fappening" have cameos.

Courtroom Drawings (Steubenville Rape Case, Text Messages Entered As Evidence, 2013) (2014) feutre sur papier; dimensions de l’installation variables (avec l’aimable permission de l’artiste et de Susan Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects)

Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

It’s a weird time to be a woman online. Open any newspaper (or rather, load the homepage of any news outlet) and you’ll likely see at least one story blaring scary new words like “sexting,” and “revenge porn.” You might even spot a reference to a recent high-profile act of violation disgustingly known as “The Fappening,” in which several celebrities had their personal computers hacked by people looking to find and distribute their private photos. While the Internet, social media, and instant communication have revolutionized our culture—ostensibly for the better (although that’s always up for debate)—it seems women have consistently gotten the short end of the tech-revolution stick.

At the inaugural Montreal Biennial, two artists are taking on these challenges headfirst. Using the show’s theme, “L’avenir/Looking Forward,” as a guise, Jillian Mayer and Andrea Bowers tackle feminist issues that have recently made headlines in a way that not only challenges us to be better today, but forecasts what is hopefully a brighter tomorrow.

Jillian Mayer, 400 Nudes (2014)

Mayer’s 400 Nudes explores what is probably the seediest underbelly of Internet culture—the public dissemination of nude photographs of women without consent. Typically perpetrated by vengeful ex-lovers, there are currently hundreds of websites where these images can be posted, often with the full name of the woman attached. This can be life-ruining, especially since Google Images can pull up these photographs whenever someone searches for you. Sourcing 400 images of women from these sites, Mayer superimposed her own face over theirs. At the Biennial, these images are displayed on a shelf. Online, however, Mayer has uploaded the creations under her own name, so that eventually, 400 nude images of other women will appear on Google as if they are images of Mayer.

It’s a brave action that attempts to assuage some of the pain and humiliation many women have felt when they’ve found themselves compromised online in a way they never intended to be. It also opens a dialogue about the consequences of a culture that disseminates information without consent. Mayer recounts watching visitors approach her work during the opening reception, only to become visibly uncomfortable and back away. Part of it is just the natural response to encountering something sexually charged in a public space, but Mayer posits there’s something else at play too. “Because we are used to seeing nudity in a context where it is being taken from a woman, we feel we’re not supposed to be looking at these images, which in a way harms our [ability to enjoy] sexuality,” she observes.

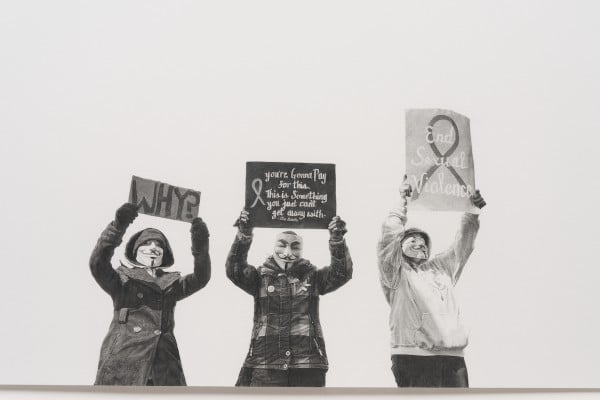

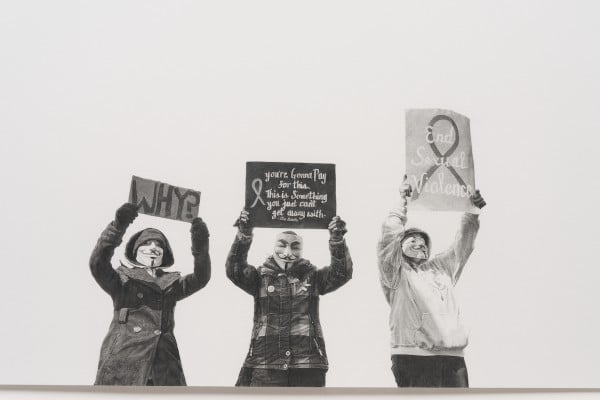

#justiceforjanedoe, Anonymous Women Protestors, Steubenville Rape Case, March 13 – 17, 2013 (2014,) graphite sur papier; (collection du Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont, CA; avec l’aimable permission de l’artiste, de Susan Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects et du Pomona College Museum of Art)

Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Tugging on a similar thread is Andrea Bowers’ Courtroom Drawings (Steubenville Rape Case, Text Messages Entered As Evidence, 2013), which detail the text message exchanges between Jane Doe, her rapists, and other central figures in the Steubenville rape case over the days immediately following the harrowing incident. Plastered on an entire gallery wall are hand-drawn sheets of blue and purple emblazoned with descriptions of the acts you may have already seen in the news. As the viewer, you must use them to try to piece together the senselessly cruel and sad things that occurred that night, just as Jane Doe had to do in the days following her assault.

Bowers, an Ohio native, was present during the courtroom proceedings and she and two others jotted down the texts as they were read aloud as evidence. Courtroom Drawings is currently the only place where all the text messages are assembled in the same place for the public to read.

It’s undeniable that the text messages and tweets that several of the boys present that night sent reflect the absolute worst of instant communication technology. But without them as evidence, it would have been considerably more difficult to place blame on the guilty parties. In this sense, it sheds a ray of hope on the future of technology in women’s lives. As does a small pencil drawing placed on the wall next to the Courtroom Drawings depicting three members of the hacktivist collective Anonymous, who were instrumental in bringing justice to Steubenville. The drawing serves a palate cleanser after being immersed in such hateful language, as well as a testament to the Internet’s ability to unite people around a cause and a reminder that there are good people out there.

The Montreal Biennial/La Biennale de Montreal is on display in various locations around Montreal, QC until January 4, 2015.