People

Cory Arcangel’s Latest Artwork Is a Kim Kardashian-Themed Video Game. What Does It Mean? Don’t Ask Him

Arcangel says talking about his artistic intentions is hard. We asked him about them anyway.

Arcangel says talking about his artistic intentions is hard. We asked him about them anyway.

All art evolves with time: what was once cutting edge may now feel outmoded, while something that was previously forgettable might today seem prescient.

Few artists are as tied to this cycle as Cory Arcangel, who is known for his alternately crude and clever interventions into the technologies that are so embedded in our daily lives, we forget to take account of their influence. He’s hacked Nintendo cartridges, created computers that send “out of office” replies back and forth to each other forever, and reimagined Modernist musical compositions with Youtube videos of cats walking on pianos.

Often, his efforts look beyond their time: for the 2004 Whitney Biennial, for instance, he developed a software that would allow users to order Dominos pizza online. But it’s a double edged sword. Tied to technologies that, by design, are only temporarily useful, his work can also feel anachronistic just years after it was completed. Sometimes it all feels a little ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

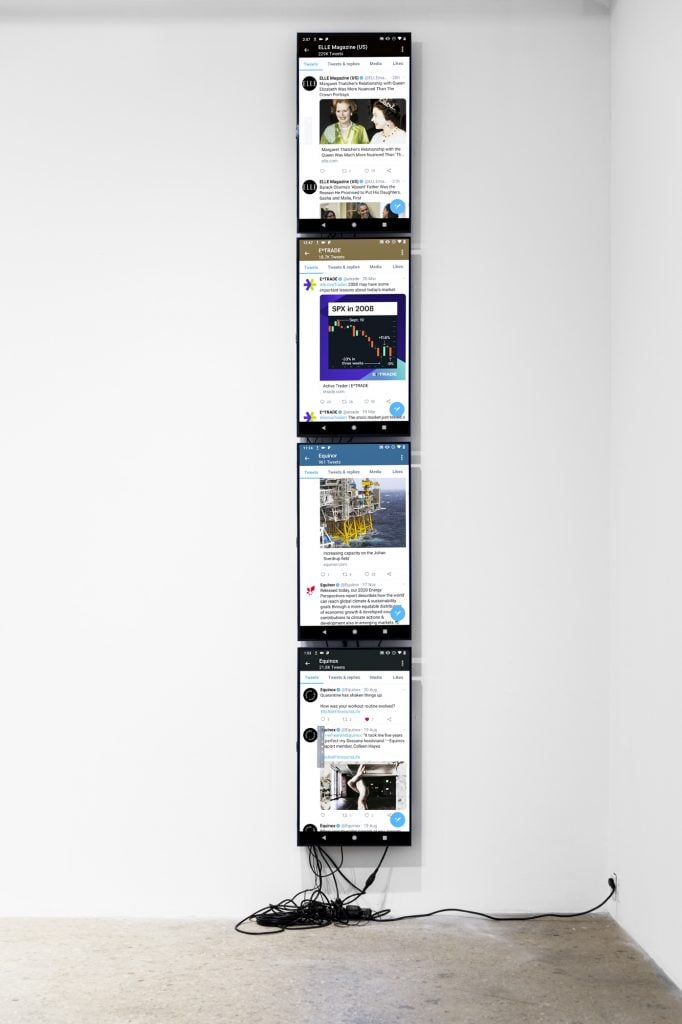

It’s a tension that’s tangible in Arcangel’s latest exhibition, “Century 21,” at Greene Naftali gallery in New York. On view are examples of the artist’s Flatware series of wall-mounted reliefs, which he makes by transferring images of cheap clothing onto Ikea tabletops, as well as new video pieces that document Twitter “performances.” In elleusa, equinor, equinox, etrade_financial—to name an example from the latter group—we look on as a bot likes every post on the titular brands’ Twitter pages. It’s rather boring to watch, but that’s the point.

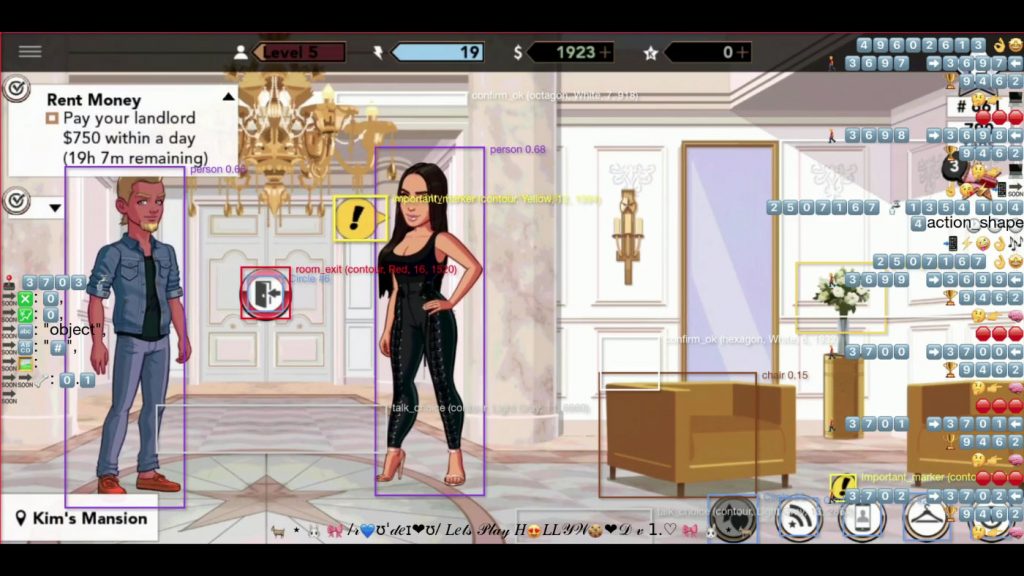

At the center of the show is /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD, a customized computer that plays, in real time, a retro-looking Android game called Kim Kardashian: Hollywood. The goal of the game is to build the fame and reputation of the player’s avatar, and through advanced machine learning, the computer slowly figures out how to do this as we watch on via several large LED screens. For those that have followed Arcangel’s now two-decade-plus career, you’ll recognize similarities to his interventions into games like Super Mario Bros and Tetris. But there’s a key distinction, too: whereas in previous efforts the artist controlled the absurd logic of the game, this time, the game does all the controlling on its own.

On the occasion of the show’s opening, Artnet News spoke with Arcangel about the artworks in his new show, his interest in archiving, and the joy of watching a piece evolve over time.

Cory Arcangel, elleusa, equinor, equinox, etrade_financial (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

I want to start by asking about elleusa, equinor, equinox, etrade_financial. That work presents as critique of Twitter bots and the artificiality of social media influence. But it also is a Twitter bot, blindly giving the brands mentioned in its title promotion. I wonder what you were thinking about with that work.

I can start by telling you what it is, and then try to work my way out to the intention. Although, for me, often, speaking about intention is hard. I can tell you why I was interested in making a work, but I can’t necessarily tell you what I was intending to communicate.

The piece is a screen recording of a performance that happened on Twitter on November 30, 2020. My studio wrote a Twitter bot and all that it does is go onto a cell phone, scroll down a Twitter profile, and just “like” every post. So what you see in the show is a recording of four different performances. One was liking Elle USA, the fashion magazine. The second was Equinor, which is the Norwegian state oil company. Equinox is the third and E-Trade financial is the fourth.

It is a real thing that happened on Twitter, and in that sense, the actual work itself—disregarding the sculptural element—is a documentation of a performance, or four separate performances. For the sculptural version of the work, which you saw in the gallery, the performances are presented on flat-screens that are stacked one on top of each other, like a Jenny Holzer sculpture—that was what I was thinking of, at least.

Seven or eight years ago, I started this series of works called “Surfs,” which were recordings of me surfing around websites. I have one where I visited Dunkin Donuts’ website, another where I did Subway—there are a few in the series. I thought of them as cinema, and would show them that way. So you would sit down in a theater and watch like an hour of me clicking through Subway.com, their YouTube page, their Twitter, and so on. That was the first time I’d ever done this kind of recorded performance using the computer interface.

At the time, the big hot topic of the day was the dark net—this idea of the invisible internet and alternative encrypted networks. But I thought about it from the opposite perspective, that the true dark net was all these parts of the web that are there for almost nobody. Like who clicks on the 400th page on Subway.com? I wanted to capture what these websites looked like at that time and then also try to stretch these recordings into cinema. Fast-forwarding to the Twitter bots—they’re definitely coming out of that earlier series, except they’re automated.

What I’m trying to express, that’s tougher. Fashion, fitness, finance, and petroleum—I wanted to capture today’s moment through these four poles, and their related brands, which have bizarre social media identities. Also, they’re totally ephemeral. We think that they exist, but actually they don’t. I mean, if no one ever bothers to record them, do they?

You having trouble identifying your intentions makes sense to me. I mean, it’s an unfair question to ask in some ways, but also it seems to me that much of your work is less about putting forth an agenda, and is more often about posing questions we don’t think to ask—even if it does occupy a space, such as the internet, that tends to be hyper-politicized in contemporary art.

For me, it’s an energy. I know the energy I’m after and sometimes it’s a hit and sometimes it’s a miss. I don’t always know what I’m doing. Each work is an exercise in, “Okay, I wonder if this is going to work.” It’s a little bit like being in a room with the lights off and feeling your way around the wall. You just go inch by inch by inch and say to yourself, “I’ve made it this far now, maybe a little bit farther.” With the totem work that we just discussed, I started inching my way toward that piece 10 years ago.

I’m not trying to communicate something concrete; I’m trying to communicate a feeling. I know the feeling and I know it when the salt and pepper in the work is right. But it’s a lot of trial and error, and a lot of the work is really just experiments. For “Century 21,” the feeling I was after circled around some kind of petroleum age supply chain exhaustion—power, track-suits, GPUs, one-click shopping, “you might also be interested in”, et cetera.

Cory Arcangel, /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD (2017-21). Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

That’s a nice segue into the next question I had for you, which was about /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD. This is familiar territory for you, altering a video game. But this a more evolved version than previous examples like your Mario interventions, say, or Various Self Playing Bowling Games. Do you consider HOLLYWOOD to be in the lineage of those older works?

It’s definitely in the lineage. If you can believe it, it’s been almost 20 years since some of those Nintendo works, which is crazy. Those works are so far in the past now that I actually enjoy showing them again.

The way they’ve aged is interesting too, I think. What once seemed like ironic, hamfisted hacks now read more like charged gestures of human intervention.

The artworks are older than those games were when I made the works! That’s one of the reasons I like them again, because they read so differently. That’s one of the great things when you make something—not only do you not know how it’s going to be received, but you also don’t know how it will change over time. And watching the works change like that is kind of mind blowing. It’s totally out of your hands; you have nothing to do with it, you can’t even understand it.

To get back to your original question, it’s definitely in the lineage. Those Nintendo works came first and then in the 2010s, I started making self-playing games. For those, I had worked with an engineer to create a little chip that would record the button presses and play them back into a video game controller. I recorded all these really dumb games—a basketball game where the shooter always missed the hoop, or a bowling game where the ball always ended up in the gutter. Then when you could turn the whole system on and it would just do it over and over again, the same exact thing forever.

But now, 10 years later, /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD is a whole different beast. The game itself has not been modified. It’s off the shelf and the technical apparatus here is what I call a super computing machine—/roʊˈdeɪoʊ/. With two GPUs, it’s a carbon-guzzling monster, and the only thing it can do is click, double click, scroll, and restart the game; it can’t do anything that you can’t do with your fingers. And the difference between this and the self-playing games is that it’s not pre-recorded. /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD is a living, learning thing. So in a way it’s a continuation of ideas I’ve explored previously, but it’s no longer low tech or obsolete or even canned. This is as high tech as you can possibly get. It took us years to build it and get it working and there was a lot of stuff that was totally new for me.

You’ve also made it clear that it’s operating in real time, overlaying the background labor of the interface.

Exactly. I’ve always tried to make the process visible. Maybe that comes from me being from Generation X—I grew up in a whole different world and I came into the industry at a time when art made with computers wasn’t considered real art. So I was always very conscious about communicating what the computer was doing. And that manifests in the works in different ways. In the case of the Nintendo works, you could see there was a hole cut in the cartridge, and with the self playing games it was that the chip that we had made was literally screwed onto the controller with all these wires.

Cory Arcangel, /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD (2017-21), detail. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

You mentioned that technology behind that piece is state-of-the-art. But the game was created in 2014, and it looks it—it looks like it’s from an older generation of digital aesthetics. This is something you’ve done a lot, manipulating a game or other piece of technology that’s one or two generations removed from our current one, but not so far removed as to be unrecognizable. What about that move interests you?

I actually had the idea for the piece back in 2016. So for me, that wasn’t really part of it; it just took that long to make the /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ computer. But things move so fast now, I can’t discount what you’re saying. I guarantee that when you see these Twitter pieces five or six years from now, it will be like, “Oh my God, they look 100 years old.” It’s like how, when you buy a car, it loses half the value as soon as you drive off the lot. Anytime you do anything with digital technology, it’s the same thing. I’ve always tried to be aware of that and think a little bit ahead: can aging be a part of my intuitive process in creating this work?

In the case of /roʊˈdeɪoʊ/ Let’s Play: HOLLYWOOD, that is a piece that is about time, in a sense. It’s becoming smarter all the time, but that game is so open-ended that it will have to click 1 or 2 million times to even start to make significant progress. It’s durational machine learning that takes place on a scale of months—years, maybe.

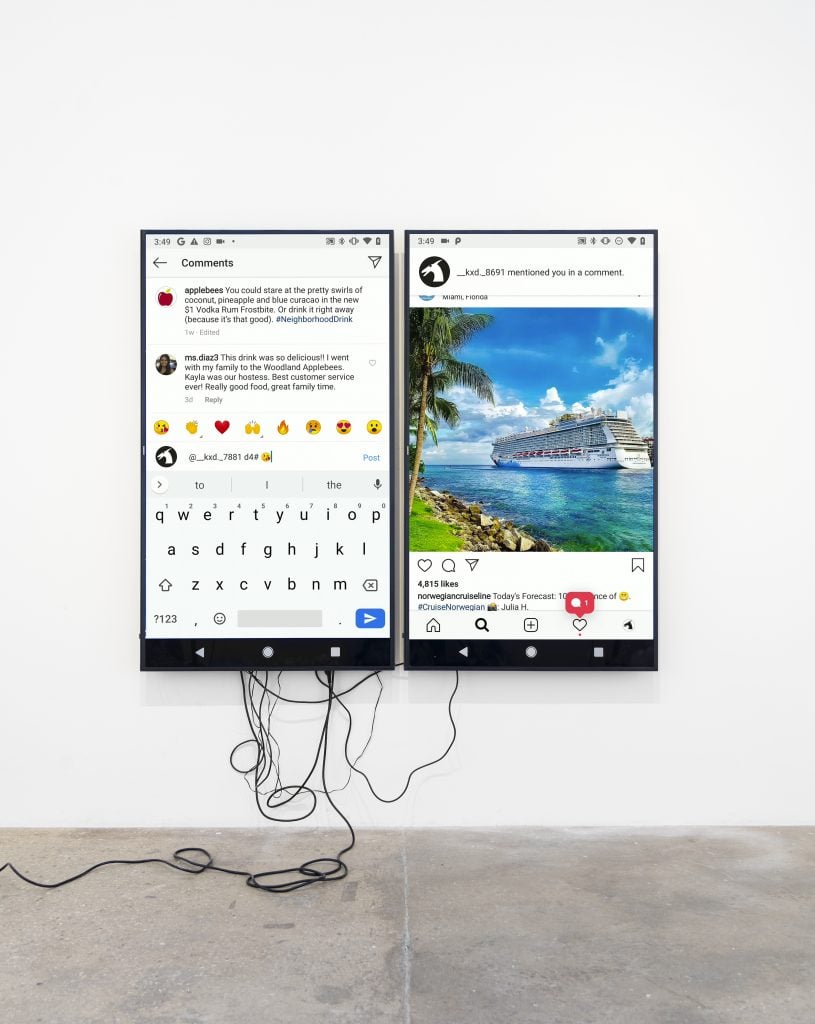

Cory Arcangel, ?? ??????? / ??? ???? c?????? ?? ??? ????? (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

That’s a theme baked into much of your work: the increasing rate of technological obsolescence—a function of capitalism—and the absurdity of trying to stave it off. But you’re also an aggressive archivist. You’re always documenting your work, making it available on newer and newer channels, and so on. Asking you why you archive might seem strange given that it is your life’s work, but then again, there are artists who traffic in similarly ephemeral media that let their creations disappear naturally with time and technological evolution—often as a conceptual gesture unto itself. Why is archiving so important to you?

That’s a great question. I totally respect the idea of an artist just letting everything disappear—my God, I would love to be that way!

An artist has two jobs: one is to make the work and the other is show business, which is everything that happens after the work is made and leaves the studio. An artist has to do both; they’re related and they play off each other. But archiving is this weird thing that is right between those two functions. Most of what I make are performances, really. That’s the real way to think about all these digital objects, which require electricity and exists in these networks—they are temporary, ephemeral performances.

Maybe it has something to do with control. The world we live in is just so chaotic. If you actually think about what’s going on, it’s so overwhelming. So for me, to keep a little quarter of my life organized gives me some kind of control. And the work is about this too, I think.

It just happens, you know? I’m not an artist who is keeping archives for, say, some political reason. It’s more like, I can’t stop. We’re losing all these things, all these beautiful moments and I just, I just feel the need to capture them, almost so much that it becomes the work itself. A lot of the work is just capturing at this point.

“Cory Arcangel: Century 21” is on view at Greene Naftali through April 17, 2021.