Linda Goode Bryant’s idea to open Just Above Midtown (JAM) in 1974, the first gallery devoted to exhibiting black artists in New York’s toniest art neighborhood, was as simple as it was revolutionary.

“Why are we waiting on someone else to do for us what we can do for ourselves?” she remembers asking. At the time, she was the head of education at the Studio Museum in Harlem and had been on the receiving end of constant complaints from African American artists about the lack of opportunities to show and sell their work. “You want to be in a major gallery district?” she recalls asking. “Let’s start a gallery down there. I’m crazy enough to try it.”

At 25, a single mother of two with few resources, Bryant talked her way into a discounted lease at 50 West 57th Street and launched a platform for black artists to exhibit shoulder-to-shoulder with blue-chip galleries that were showing white male artists almost exclusively.

Linda Goode Bryant at Tribeca Film Festival. Photo by Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for Tribeca Film Festival.

Forty-five years later, many of the artists who showed at JAM are regarded as some of the most important figures of the 20th century. A tribute to JAM’s pioneering history, and the groundwork it laid for many artists of color working today, is on view at Frieze New York this week. The Museum of Modern Art is also planning a tribute exhibition—titled “Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present”—for fall 2022.

At Frieze, Franklin Sirmans, the director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, has organized seven solo presentations by artists who exhibited at the gallery during its 12 years in business, including Dawoud Bey, Norman Lewis, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, Howardena Pindell, Lorna Simpson, and Ming Smith. (JAM gave O’Grady, Nengudi, and Simpson their first New York solo presentations.)

“In terms of opening on 57th Street at that time and what that meant in the conversation of the actual buying and selling of art, it was so important and so in your face,” says Sirmans.

Bryant, now 69, has clearly never been shy about confrontation. At 12, she announced at a family dinner in Columbus, Ohio, that she was going to be Picasso’s first black mistress—“because I’m going to be an artist and that’s the only way the world will look at my art,” she recalls now, laughing.

Ming Smith, Art Ensemble of Chicago (1979). Courtesy of Jenkins Johnson Gallery.

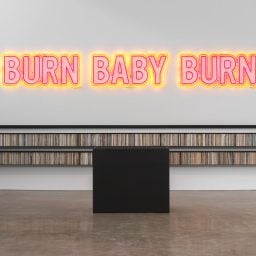

After studying painting at Spelman College in Atlanta and pursuing a graduate degree in art history at City College in New York, Bryant interviewed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a prestigious Rockefeller Fellowship, which offered special access to the inner workings of the museum. She told then-director Thomas Hoving, “I want to burn this motherfucker down.” She reasoned that it was a racist institution, sitting on public land and supported by taxpayer dollars, but only representing white folks. She got the fellowship.

In JAM’s inaugural group exhibition, “Synthesis,” Bryant took a characteristically irreverent approach, mixing the work of figurative artists with abstract painters like Lewis, and New York artists with their LA counterparts like David Hammons. The show stirred up debate among members of the Harlem-based African American community, some of whom maintained the need for empowering representational images of black life above other forms of art. “I felt the gallery needed to show all the creative energy that was going on, but the elders didn’t like that,” says Bryant, including 20th century titan Romare Bearden, who ended their friendship because of her decision to show Hammons’s work.

Bryant and Hammons’s provocations did not stop there. His first solo exhibition at JAM in 1975 was a landmark event. Hammons had already developed a dedicated following for his series of body prints, which Bryant had promised in advance of the show to black professionals she was cultivating as collectors. But when she called Hammons asking for an image of a body print for the invitation, he gruffly retorted: “I’m not doing body prints anymore!”—derailing her plans to pay the phone company, printer, and wine and cheese suppliers with proceeds from the expected sales. Instead, he said, “I’m doing brown paper bags, grease, hair, and wire.”

Norman Lewis, Untitled (1974). Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

At the mobbed opening, “there were angry whispers and folks were outraged” at Hammons’s new direction and use of such lowly materials, says Bryant. She finally clinked a wine bottle and promoted an open debate. Topics ranged from making art with barbecue bones versus art supplies to the requirements the art world imposes on creativity.

“It was an exchange of ideas, disagreements, perspectives between black artists that I have never experienced since,” says Bryant. “In that moment, the friction between figurative and non-figurative, New York and Los Angeles, went by the wayside. We all became family.”

One of Bryant’s superpowers is her ability to bring previously siloed communities together. “Linda set up a situation where we were not isolated,” says Howardena Pindell, who had one of her earliest solo shows in 1977 at JAM and had experienced opposition from the Studio Museum for choosing to work abstractly. “I remember JAM as a community of artists. The art world can be a very rough trip. It was a real uphill climb because there was so much resistance to not only women but people of color in the mainstream galleries. There wasn’t really a market for us.”

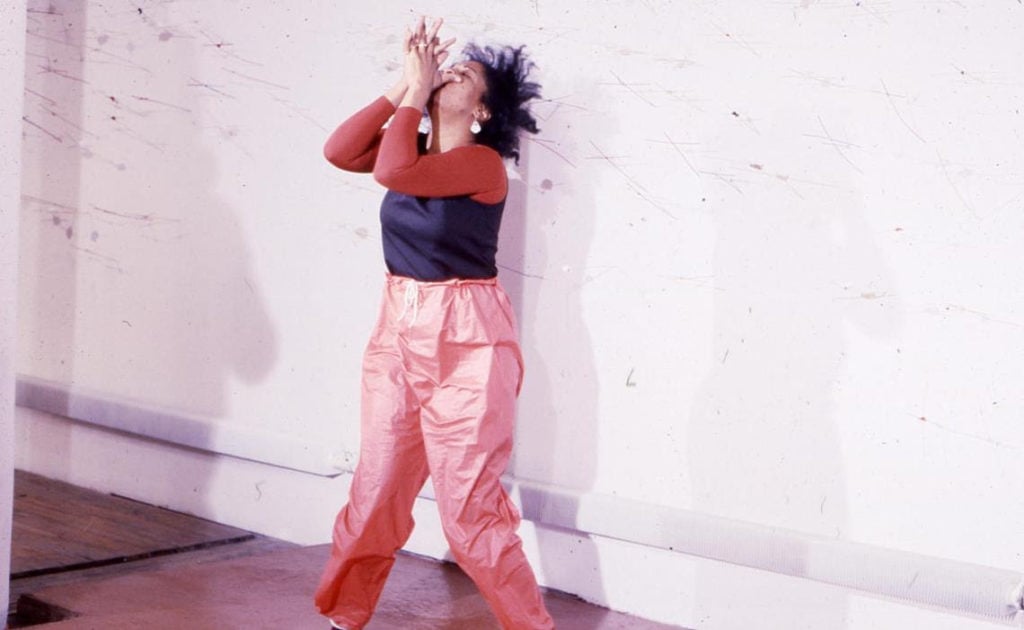

Howardena Pindell, video still Free, White, and 21 (1980). © Howardena Pindell. Courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, NY.

Of course, the art market has transformed dramatically since then, with galleries now vying for pioneering artists of color who have long been overlooked. Valerie Cassel Oliver, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, points to JAM as one of “these important sites that sustained people we are now celebrating.” Her concern is that such venues “are experiencing a sense of erasure by institutions who are now supporting these artists as if they were just sort of ‘discovered,’” she says.

The increasing commercialization of the booming ‘80s art market—as well as mounting pressure from her landlord—eventually left Bryant disillusioned and led her to close JAM in 1986. She pursued a new chapter as a filmmaker, co-producing, with Laura Poitras, the 2003 documentary Flag Wars, about the evolution of a working-class black neighborhood that became gentrified by gay white residents in her hometown of Columbus.

Despite her shift away from the commercial art world, Sirmans maintains that “the fair experience is actually the perfect venue to do an exploration of Linda.” Frieze is contributing an undisclosed percentage of booth fees from galleries participating in the JAM tribute section and paying for a fundraising breakfast on May 2 in support of Bryant’s current endeavor, Projects Eats, which she began to pursue after her work in film.

A view of Linda Goode Bryant’s Project EATS, courtesy of Project EATS.

“For me, Project Eats is a continuation of JAM, I’m just doing it differently,” says Bryant, who in 2010 began partnering with residents and organizations in low-income areas around New York to launch community farms providing healthful food. “How do we create something that directly has an impact that’s tangible where it occurs,” she says. “Farming is one form of that.”

One of these farms is on the grounds of a men’s homeless shelter on Randall’s Island, not so far from the Frieze tent. Bryant is interested in contextualizing for visitors to Frieze its relationship to the surrounding area, which has many such shelters. “Can we, through the energy that we put in that space, cause people to pause for a moment and think beyond the purchase of art?” poses Bryant.

“I have to revert back to something Linda said in regard to why she even started the gallery in the first place,” says Sirmans. “She saw the ability of art to affect socially and economically the conditions where it takes place. That’s kind of shorthand for believing that art can change the world. That’s literally what her new project is doing.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.