Art World

Was King Tut’s Legendary Dagger Actually Made From a Meteorite?

Hieroglyphics have referred to 'iron of the sky.'

Hieroglyphics have referred to 'iron of the sky.'

The legend of King Tut has lost some of its shine in recent years: The fabled boy king, it turns out, was probably born with the misshapen features that earlier archaeologists attributed to injuries sustained in a fatal chariot crash. If anything can restore Tutankhamun’s tarnished image, however, it’s the recent discovery that the dagger he was buried with may be made from a meteorite.

The 13-inch iron blade, laid to rest alongside the fallen king, has a beautifully-embossed handle with a crystal pommel and is enclosed a golden sheath decorated with a jackal’s head, feathers, and a floral pattern. The Daily Mail, which characteristically dubbed the weapon a “space dagger,” reports that the composition of the metal was examined by researchers at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Milan Polytechnic, and Pisa University using an x-ray scanner.

A photo of King Tut’s dagger from “The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun’s iron dagger blade.”

What they found, according to the newly published article in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science titled, “The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun’s iron dagger blade,” was a great deal of nickel and traces of cobalt and phosphorus, at levels that “strongly suppor[t] its meteoritic origin” from a meteorite found in Marsa Matruh in 2000.

“Our study confirms that ancient Egyptians attributed great value to meteoritic iron for the production of precious objects,” wrote Daniela Comelli of Milan Polytechnic, who led the research project, in the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science. Comelli notes that there are examples of hieroglyphics that refer to “iron of the sky” suggesting that the ancient Egyptians “were aware that these rare chunks of iron fell from the sky” some two millennia before meteorites were discovered by Westerners.

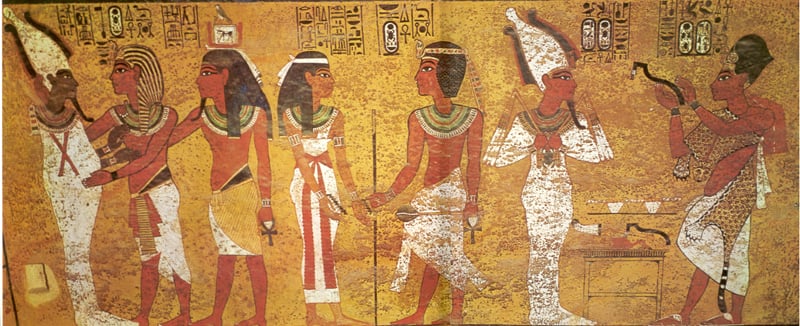

Archaeologist Nicholas Reeves believes this painting in King Tut’s tomb marked the closing of Nefertiti’s now-hidden burial chamber. Courtesy the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“The sky was very important to the ancient Egyptians,” Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, of the University of Manchester explained to Nature. “Something that falls from the sky is going to be considered as a gift from the gods.”

The blade is a rare example of an ancient Egyptian artifact made from iron. Considering its advanced age, the dagger is well-preserved, and shows no visible signs of rust.

King Tut’s burial mask as compared to a newly-generated image of his face.

It’s the first bit of good news for Tut in quite a while. Recent headlines have centered around the botched restoration of his iconic funerary mask, ineptly restored by museum workers who are currently facing disciplinary action, and the likelihood that his famed tomb was actually a hasty addition to a larger burial complex honoring his stepmother, Nefertiti, thought to be still hidden within a secret chamber.