Art World

5 Things to Know About Britain’s Most Notorious Art Forger

He wrote his memoirs in prison to avoid sketching inmates' portraits.

He wrote his memoirs in prison to avoid sketching inmates' portraits.

Shaun Greenhalgh is one of the world’s most prolific art forgers. Between 1978 and 2006, the Bromley Cross, UK native created hundreds of masterful forgeries of paintings, sculptures, and artifacts in the style of Ancient Egyptian craftsmen, Renaissance masters, Impressionist greats, and everything in between.

In March 2006 he was arrested and subsequently sentenced to four years and eight months in prison, where he wrote a memoir, A Forger’s Tale, to set the record straight about his legally sketchy career. A new edition of the book is coming out on Thursday via ZCZ Editions, and the Guardian’s Simon Parkin had an in-depth talk with Greenhalgh on the occasion.

Here, we bring you the top five takeaways from the interview.

1. Greenhalgh began his career as a forger at age 13

A natural-born artistic talent, his first source of income came from selling pot lids and clay pipe busts that he made at school at sold at local flea markets, telling buyers they were antique and he had dug them up.

As a child, he visited Rome with his late parents (who later became complicit in his forgery scheme), where he became inspired by the work of Sandro Botticelli, Perugino, Signorelli, and Raphael. In comparison to the Renaissance masters, he said, “I felt so insignificant,” but he later learned to emulate them brilliantly.

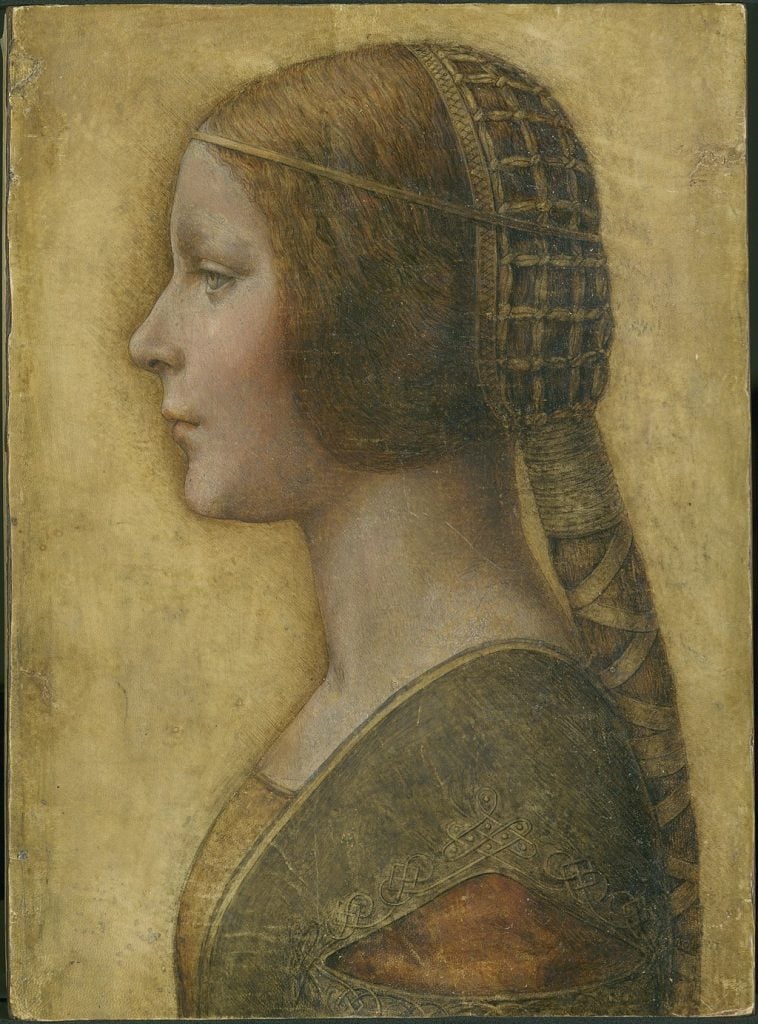

Leonardo da Vinci, La Bella Principessa (1495). Forger Shaun Greenhalgh also claims to have created this work. Courtesy of a private collection.

2. He learned how to fake a convincing provenance from a shady employer

In the early 1980s, Greenhalgh met an art restorer, whom he knew as “Tom,” who commissioned copies from him throughout the decade. Tom fabricated provenances for the forgeries, and sold them at a mark-up. Eventually, Greenhalgh began to feel exploited, and the two had a falling out. That’s when he began selling his forgeries to dealers himself.

“I thought, I’ve been selling stuff for living prices, but not proper money,” he said. “They are all doing it. I have the ability, they don’t. They profit. I don’t. I was bitter. And now I knew how to do the provenances.”

He put “tells” into his copies to test dealers, but his provenance-forging skills soon reached the level of his technical ability. “No matter how many mistakes, [dealers] were always blown away by the provenance. Often they hardly looked at the work,” he said.

3. He always felt guilty about making forgeries

“I’ve always had a tinge of guilt—I probably get that from my mother. Something within me knew it wasn’t right,” said Greenhalgh.

A sculpture made in the style of the Egyptian Amarna period exacerbated that. A curator of the British Museum hailed it as a half-million dollar masterpiece—but Greenhalgh says he “always loved that museum,” and didn’t make any work for years after it sold.

In prison, he was offered early release, but declined. “I’ve done the crime, I’ll do the time,” he said.

A sculpture of faun displayed by the Art Institute of Chicago as a Paul Gauguin, actually a forgery by Shaun Greenhalgh. Photo by Carlos E. Restrepo, cerdsp, GNU Free Documentation License and Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

4. He wrote A Forger’s Tale to avoid drawing portraits of other inmates’ loved ones

“I thought, if I start that, I’ll be absolutely snowed under,” he said. But the memoir also served the purpose of setting the record straight, and countering slanderous remarks from journalists against him and his family.

5. Now, he uses his skills to make copies for documentaries

Sunday Times art critic Waldemar Januszczak once bought a “Gaugin” forged by Greenhalgh, but despite that, Januszczak later commissioned him to make a copy of an Anglo-Saxon brooch to be featured in a TV documentary. Other filmmakers followed suit, including the BBC, which paid for part of a new workshop.

If the forger had another chance, he would have become an art teacher. He doubts, however, that he could make it as an artist in his own right.

“The problem is,” he said, “that I can’t find my own style.”