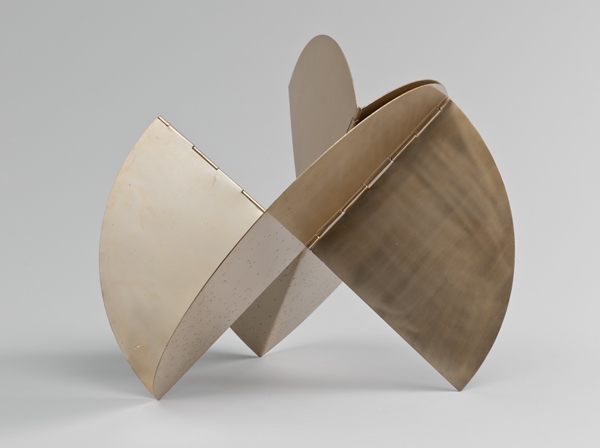

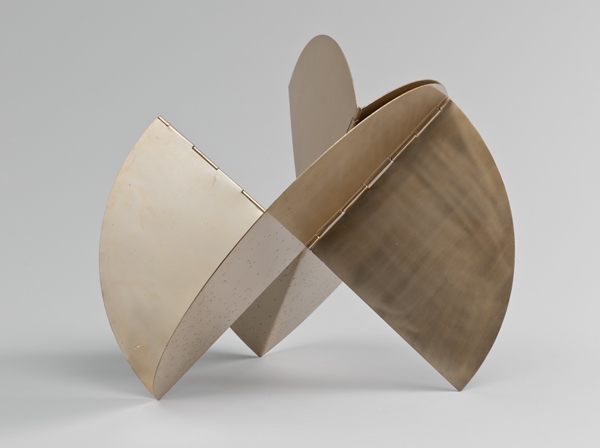

I’m late to the party to cover “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948-1988,” the retrospective of this interesting, difficult, underknown Brazilian artist at the Museum of Modern Art. The show focuses on a generous number of her abstract paintings (mainly from the 1950s); a selection of her metal tabletop sculptures made of hinged interlocking plates, the “Bichos” (from the early 1960s); and a final gallery featuring film clips of collective ceremonies that she staged and examples of art-props that she made later in life (from the late ‘60s and 1970s)—soft masks with spices in them and mirrored goggles that let you see yourself—before she at last abandoned art completely to become a sort of healer in the late ’70s. There are several good reviews that you can read to take you through an assessment of the objects in the show. My starting point, though, is what’s missing here, inspired by a passing comment by Roberta Smith, that what the exhibition lacks is “a better sense of the woman and her life.”

That’s true and it’s too bad. The impression I have of this retrospective is one of reverse transubstantiation: flesh and blood are transformed into starch and sugar, and an unsettling rebel into someone whose highest ideal seems to have been to appear in an introductory art theory survey. Clark is commemorated as a pioneer, first of interactive art and then of participatory performance—themes that are everywhere these days. But without a better sense of the thorny drama of her biography, it’s easy to forget, today, in a world of social media and flash mobs, Google Glass and Oculus Rift, that the dissolution of “art into life” was a truly radical art theme of the ’60s and ’70s, one of the ways which fine art and the counterculture merged into one gumbo in the churning cauldron of a decade of political cataclysms. For me at least, digging into Lygia Clark’s writings drastically changes how I think about the meaning of her contribution. So let’s dig in.

Lygia Clark, Sem titulo (Untitled) (1952). Private Collection, Rio de Janeiro.

Photo: Courtesy Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro.

Dysfunction and abstraction

Recently, her son Eduardo summed up the material basis for the inexhaustible experimentation of Lygia Clark’s career in the following, striking way: “My mother was born rich, married a rich man, and, upon her separation, received 86 apartments, which she sold off one by one to support her work.” Married at 18, she had three children in a decade—Elizabeth (b. 1941), Álvaro (b. 1943), and Eduardo (b. 1945)—before deciding to move from her native Belo Horizonte to Rio de Janeiro and reinvent herself as an artist, in 1947. Later she would say that it was the “postpartum psychoses” of her last pregnancy that triggered her transformation, one of an endless series of mental crises.

Clark’s mad dash towards art in her late 20s was also of a piece with her attempt to escape the conservatism of her background. In a vivid letter to fellow artist Hélio Oiticica in 1971, she described a violently abusive relationship with her father, as well as being institutionalized as a girl (in the catalogue, Antonio Sergio Bessa says there is some question as to whether this last is a fiction). Her childhood home was, in her mind, a snake pit of patriarchy and alienation: “I grew up feeling outside the family, trying every night to tear out my little clitoris, which I experienced as a sign of marginality.” She wrote of needing “an entire life to recompose or build a personality that is never finished.”

The crisp, accomplished, but rather decorous 1950s paintings that occupy most of the MoMA show may seem today like unlikely channels for someone looking for a vehicle for spiritual redemption. But in the desperately underdeveloped Brazil of the 1950s, geometric abstraction was charged with a particular missionary zeal, associated with aligning the country with nourishing technological progress. It was art on a mission. Brasília, the custom-built modernist capital completed in 1960, would be the crowning signifier of this symbolic alliance, and Clark’s early art mentor, Roberto Burle Marx, did the landscaping for Brasília. When, in 1950-51, Clark made the first of her sojourns to Paris to escape Brazil, she studied with Fernand Léger, a Communist and, with his image of universal harmony achieved through the synthesis of man and machine, the most utopian of all the Cubists.

In a truly extraordinary “Letter to Mondrian” of May 1959, Clark expressed her faith in the idea of an art that could literally heal the world around her: “If I work, Mondrian, my reason is more than anything to achieve myself in the highest ethical-religious sense. It’s not just to make one surface and another.” But she also adds something to indicate that she was still searching, spiritually: “Mondrian, if your strength can serve me, it would be like a raw steak placed over this painful eye so it can see again as quickly as possible and can face this sometimes painful truth: ‘the artist is a lonely person.’”

Lygia Clark, Relógio de sol (Sundial) (1960).

Courtesy: The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in honor of Rafael Romero. Courtesy Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro.

Interactivity and sexuality

Smith speculates that understanding Clark’s class background might help unlock the meaning of her art, and I think it does, in the following way: Clark was born into the ruling class of a very poor country. She experienced the nasty side of Brazil’s establishment up close and very personal. But the same circumstances meant that she was isolated from the experiences of the majority of Brazilians: “Our group wasn’t very popular, as it was a group of intellectual artists who had no contact with the people,” she remembered later of the Neo-Concretists, a movement that attempted to build a more organic, Brazilian brand of abstraction that she was associated with for all of two months in 1959.

Clark was intimate friends with radical Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa (1900–1981), secretary of the Trotskyist Fourth International, a cause célèbre of left-leaning artists in the 1970s for his stance against the dictatorship, and, in 1980, a founder of the Workers Party, which rules Brazil today. She was inspired by Pedrosa’s idea of the political value of art as “the experimental exercise of freedom,” and addressed him in several passionate letters as “my commander.” As far as I can tell, however, Clark’s writings to Pedrosa—or in general—are remarkably slight on political detail for someone who lived through such dramatic political times: in 1964, the rise of a military dictatorship (Kennedy had personally instructed the CIA to undermine the Goulart government); in 1968, the intensification of state repression, including of the countercultural Tropicália movement, which she was associated with. In the MoMA catalogue, co-curator Cornelia Butler notes that, although she came to Paris around the time of the political explosion of May 1968, “Clark herself neither wrote about this nor accounted for it explicitly in her work.”

The upshot is that Clark’s many transformations were impelled by an extravagant rhetoric about art’s ability to change the world that was somewhat otherworldly. Clark’s best and most famous works, the “Bichos” series of sculptures, broke ground in that they invited viewers to pick up and handle them. They marked a rejection of abstract painting for something more ambitious, and Clark made big, big promises for them: “When a man plays with the Bichos,” she declared, “he begins the adventure of separating from this ethical concept and learns his own separation from all that is fixed and dead.” Without underestimating how exciting it was in the early ’60s to make tactile art, this is clearly overselling things a teensy bit.

Clark herself sensed this incongruity. Thus, in 1963, she was on to something still more thoroughgoing, Caminahdo. The idea was to write the artist completely out of the art equation. The work consists of a simple proposition, a poetic craft activity that anyone could do: Instructions for making a modified Mobius strip. “The dualist relationship between man and Bicho, which characterized the previous experiences, is succeeded by a new type of fusion,” she explains. “In being the work and the act of making the work itself, you and it become completely inseparable.” This too, however, is rather over-the-top. At MoMA there is a small station where you can make Mobius strips. It basically feels like doing an activity at a children’s museum.

A repressed social content does lurk beneath all this overheated art rhetoric: Clark’s sexual self-discovery. Secretly, she had been since the late ’50s coming to an understanding of her art-making in relation to an elaborate mythology of sexual repression and sexual expression. “I now begin to sense the emptiness of form,” she had written in 1959, working through her feelings for abstract painting. In her own discovery of art that was not about fixed forms but that was fluid and dynamic, she saw an analogy to the celebration of the feminine: “To me, my fulfillment as a female came only after experiencing the ‘empty’ full that by encompassing existential meaning also meant encompassing in its immediate sense the awareness of my femaleness… sensing vaginal emptiness as expressive, internal, in contraposition to its external form—the reverse of the penis that the woman carries inside her.”

The ’60s was the era of sexual revolution. The coded sexual subtext of Clark’s work erupted into the open with her participatory installation for the Venice Biennale in 1968, The House is the Body. Penetration, Ovulation, Germination, Expulsion. It is, in effect, an abstract, procreation-themed obstacle course: You enter by pushing your way through a room stuffed with white balloons meant to evoke a vagina flooded with sperm, and exit through a room meant to evoke a birth canal, with a mirror and multicolored curtains, as if watching yourself being born. I can’t say that the experience, recreated on the fourth floor of MoMA, is much more than goofy, but the times were different. It’s hard to overstate how much sexual and political repression were linked in the late-1960s imagination: The epoch-defining crisis of France’s May ’68, after all, was partly touched off by the fact that students were frustrated that male and female dorms were kept segregated.

Installation view of The House is the Body (1968), part of the exhibition “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948-1988” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Photo: Thomas Griesel. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art.

Acceptance and abandonment

From 1968–76, Clark lived in Paris. Her writings of this time are littered with references to psychic crises (“I’m conquering small phobias, like entering cafes; going to the bathroom alone; passing in close proximity to people, which I feel uneasy; leaving home when I’m somatizing problems”) set off sharply against graphic language of fantastical empowerment (“I feel like a cauldron of cum, process, I feel myself entirely there, even before being born, and believe it is that mixing where now appears the little girl, the milk in the baby bottle, the adult-adulteress, the crazy woman, the five-thousand-year-old woman…”).

Clark, in her own sui generis way, was transformed by the encounter with the global youth revolts of the late ’60s. “I was called to California, where I visited several universities, and in one of them a very young American gave me a kiss on the mouth,” she remembered. “This got me out of the crisis of viewing the erotic as ‘profane,’ and opposed to the ‘sacred’ dimension, which was the expression of art.” Asked by the Sorbonne to teach a class, she began to create a series of rituals incorporating dozens of initiates, designed to awaken the “Collective Body.” At MoMA, this is illustrated by black-and-white clips of actions such as Anthropophagic Slobber (1973), which involves people gathering around the recumbent body of one volunteer, pulling thread out of their mouths and slobbering it all over him until it forms a cocoon-like second skin.

“I began to discover that my work was essentially therapeutic,” Clark recounted. “I saw homosexuals turn bisexual. I saw the opposite as well. The regressions were as intense as a drug trip.” She ultimately, however, was disappointed with how far her French students were willing to enter into her art. She even describes an incident in which she claims that her students, “after a session in which eroticism hit them too hard,” ganged up on her: “They shouted that I was amoral, that I was part of a magic Brazilian tribe and was trying to induce them into a way of life as amoral as I was.”

By the late ’70s she was back in Brazil, which was still mired in the repressive atmosphere of dictatorship. The sense that the spirited experimental scene she had previously been a part of was reined in and drained of its vitality was the background for what came next, the moment of the “abandonment of art” from MoMA’s title, when Clark turned away from the art scene entirely to focus on her new project, dubbed “Structuring the Self,” essentially a way of applying her theories about art’s healing potential to actual healing as part of a private therapeutic practice (she had four clients). She describes laying atop of her patients to try to make them regress to an infant-like state of vulnerability, and stroking their bodies with pillows and special props meant to suggest genitals, to help them overcome sexual dysfunctions.

In the MoMA galleries, I watched two women re-perform a late-period Clark ritual. One lays still in a special mattress, while the other places shells over her ears and eyes and caresses her body with various rubber tubes, inflated plastic bags, and other props, before at last covering her with a blanket. It is very strange to watch as a performance—because, after all, the intended audience is not a viewer, but the woman experiencing the ritual, which is meant to reconnect the subject with her sense of the body. From the outside, I am unable to judge whether Clark’s therapeutic propositions follow the same pattern as her many claims for her art, where she tended to promise transformative potential that went well beyond what she could really deliver. A lot of her writing from the mid-’80s seems to me like art theory mixed with Freudian psycho-babble: “The girl’s envy of the boy’s penis (an extension of the body that she does not have) would be a natural feeling, and a cannibalistic one.” Etc.

In any case, there’s no doubt that Lygia Clark carried her “art into life” in a particularly far-out way, to the point where it is very difficult to judge as art. For this reason, ultimately I think that she can be a very significant figure even if a lot of the art feels as if it is straining to say something that it can’t. There is a whiff of personality cult that surrounds her, in the way that her own theories about her works are taken as gospel while their more disorienting implications are politely passed over. That very fact points to what I think is the truth: Clark’s personal journey itself was her most important project, and the magnetic persona she created from it, which still hovers over the work like a perfume, her most significant work.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.