A version of this story originally appeared in the fall 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

In 1986, the newsprint magnate Peter Brant made what was then an unprecedented deal. The collection of the taxi tycoon Robert Scull was heading to auction at Sotheby’s, and Brant negotiated with the executor of the estate to pay more than $5 million for a majority stake in the legendary collector’s holdings before they were sold off. That November, when Scull’s collection made a total of $8.6 million, Brant walked away with a number of works he coveted—and a hefty profit to boot.

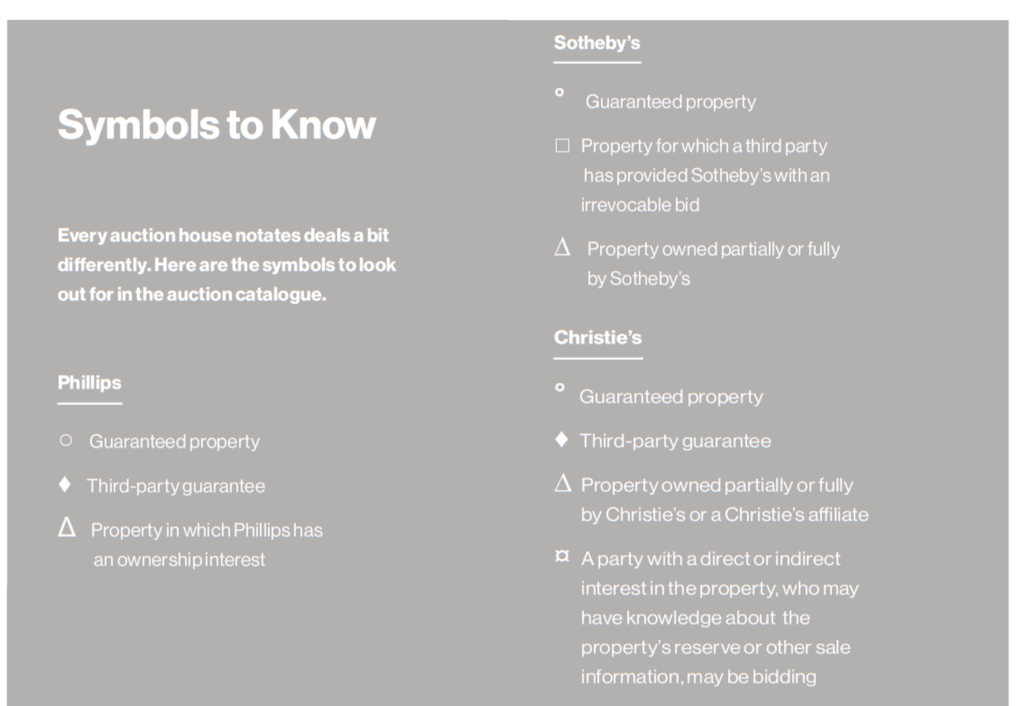

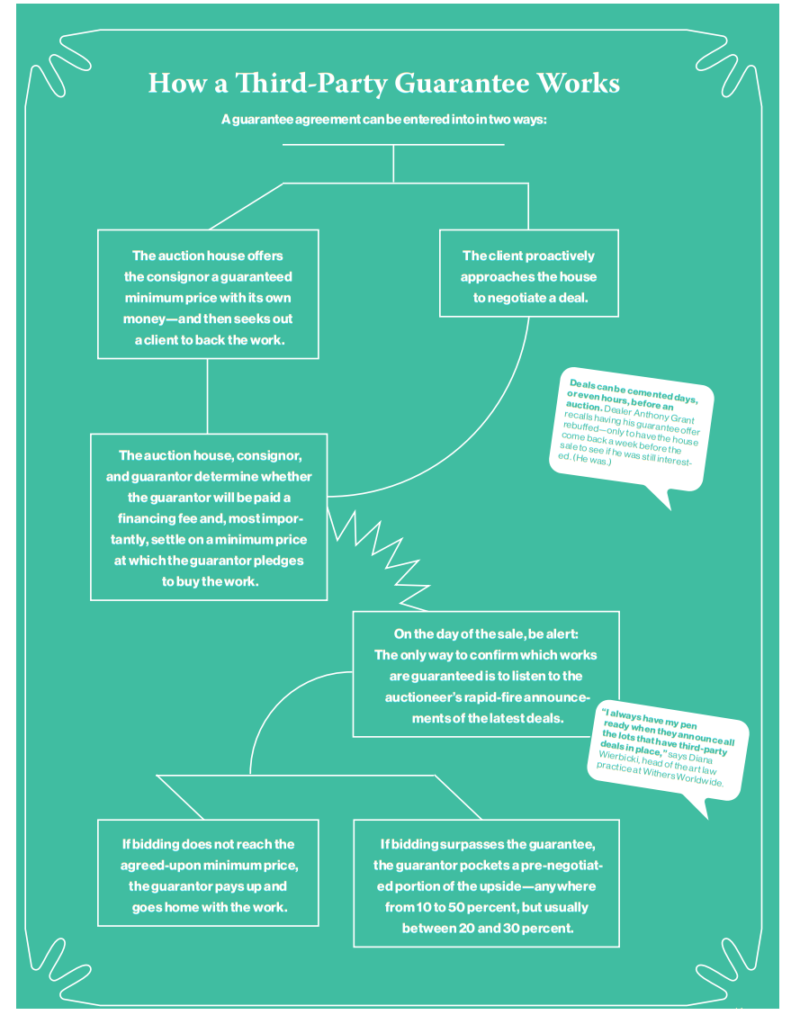

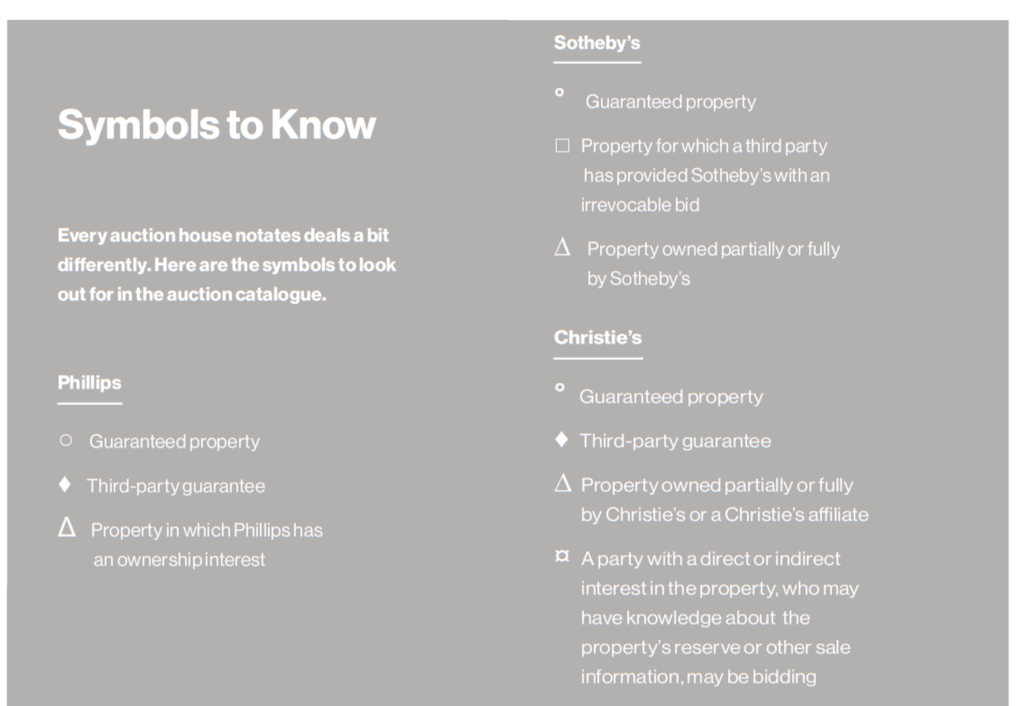

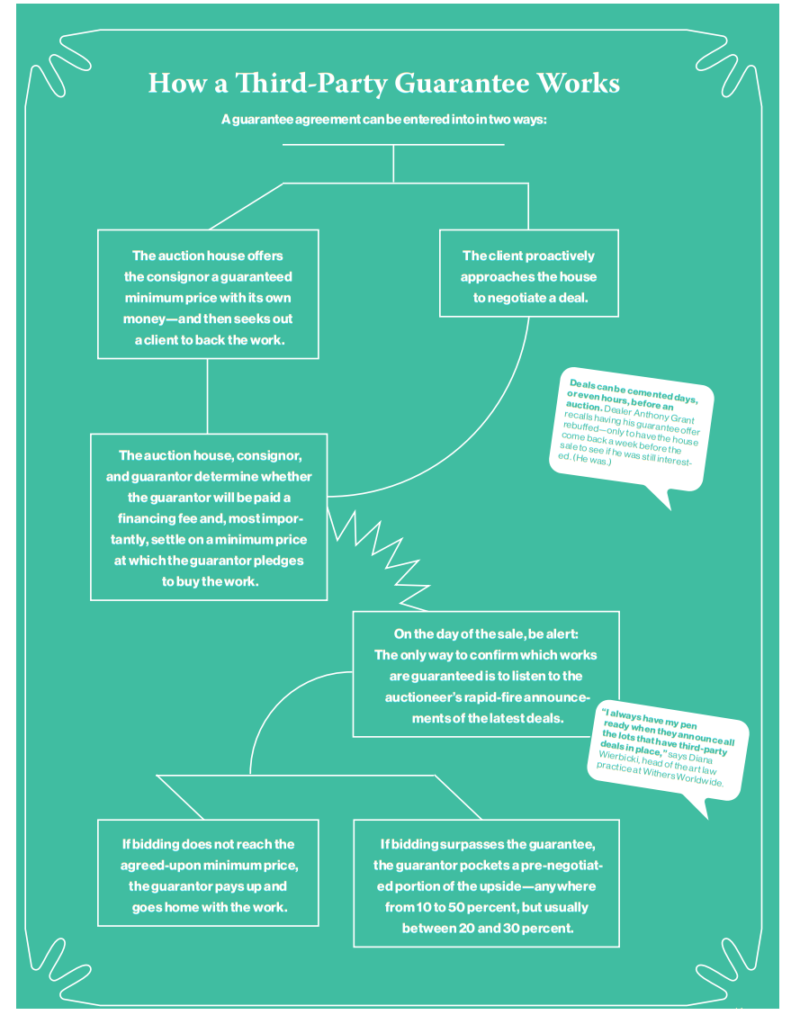

In the 33 years since this behind-the-scenes transaction, Brant’s mechanism—now known as a third-party guarantee, or irrevocable bid—has become so widely used that much of the art in a marquee evening sale may have been spoken for long before the auctioneer even picks up his gavel. A guarantee is now an accepted financial derivative that, depending on whom you talk to, either distorts the art market or offers auction houses and consignors a useful tool to hedge their bets.

“It’s magic for the auction houses,” says Christine Bourron, CEO of London-based financial firm Pi-eX. “It allows them to get the seller and at the same time pass on the risk.”

After an unprecedented expansion in recent years, third-party guarantees may have lost their magic. Their use appears to have peaked. Now, the trade is left wondering: Have guarantees become too popular for their own good? And what will happen to the market if a tool it once relied on is put back in the shed?

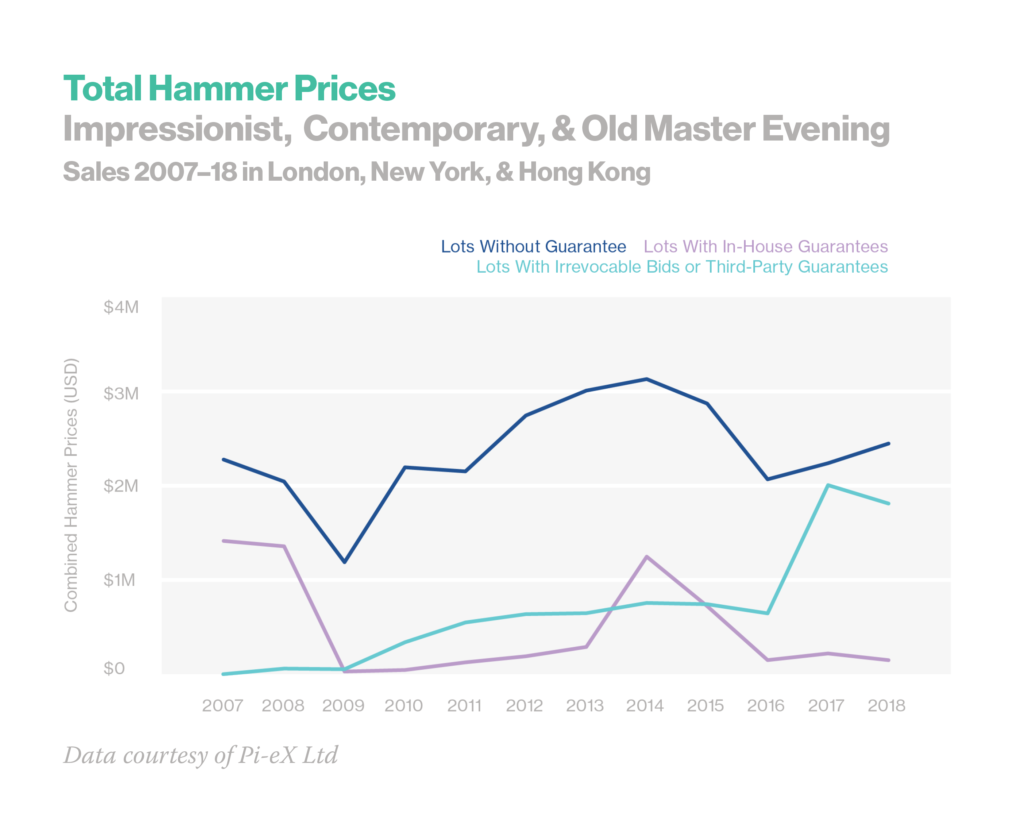

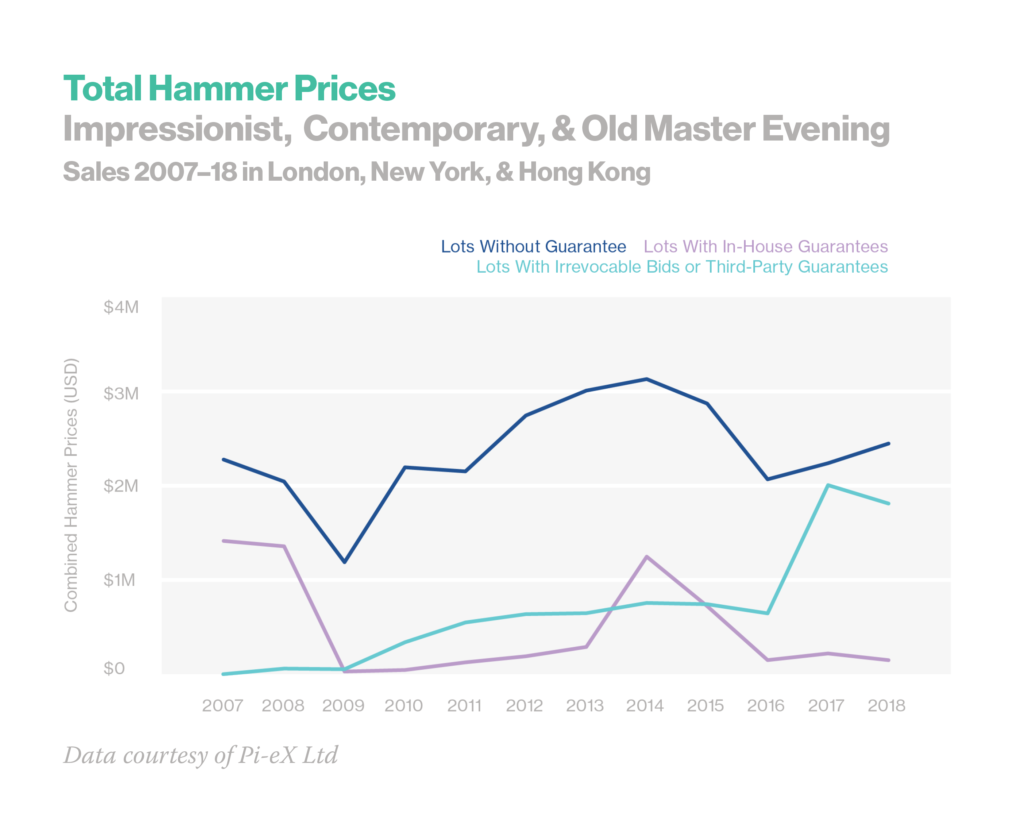

Data courtesy of Pi-eX Ltd, graphic by Artnet News.

The Rise and Fall of Guarantees

Third-party guarantees became increasingly popular over the past decade as Christie’s and Sotheby’s looked to limit their liability following a bruising 2007 auction season at the dawn of the financial crisis. After competing to attract property, they ended up stuck with a reported $63 million worth of art they had guaranteed with their own money.

As the art market regained strength around 2010, the houses had to find a way to remain competitive while limiting their exposure. The solution: farm out the risk to willing investors and offer them a reward in return.

For a few years, as the art market continued its buoyant rebound, the technique worked like a charm. But those days now seem to be numbered. Research shows that third-party-guarantee performance crested in 2017. That year, the total value of artworks sold with irrevocable bids reached more than $2 billion (based on hammer prices), according to Pi-eX. In 2018, sales of works with guarantees shrank by 10 percent, to $1.8 billion.

This downward trend continues in 2019. At New York’s May contemporary-art evening sales, the number of works sold with irrevocable bids decreased by almost 25 percent from the 2017 pinnacle, tumbling from 62 then to 47 in 2019. Looking ahead to this week’s November New York auctions, that dip continues, with the total number of guarantees at the major contemporary-art evening sales dropping to 41 (although the number could still change—deals are sometimes cemented hours before an auction).

Data provided by the houses reinforces this shift. Christie’s had a high of 38 deals in place for its postwar and contemporary evening sale in May 2017; the number for the recent May evening sale was 16, or less than half; this week, it has dropped to 15. Similarly, Sotheby’s secured 32 third-party guarantees for its postwar and contemporary evening sale in November 2018, but just 13 this year. (Phillips has reported a consistent level of third-party guarantees —around 30 percent of the works in its spring sales—over the past several seasons.).

Have Guarantees Lost Their Mojo?

This drop appears likely to continue for one big reason: Guarantees have a lower payoff than they used to. In recent years, according to Pi-eX, a growing proportion of lots with third-party guarantees have fallen short of expectations across the major evening sales in London, New York, and Hong Kong.

In 2018, almost 40 percent of the works offered with a guarantee sold at or below their low estimates. Furthermore, more and more guarantors have ended up going home with the works on which they placed advanced bids: 6 percent in 2017, 12 percent in 2018, and 18 percent in the first half of 2019.

“I’ve seen lots of very smart clients who were sure they were going to end up getting paid for a picture they had no interest in—and, to their chagrin, they ended up having to take the picture home with them at a big price,” says attorney Thomas Danziger.

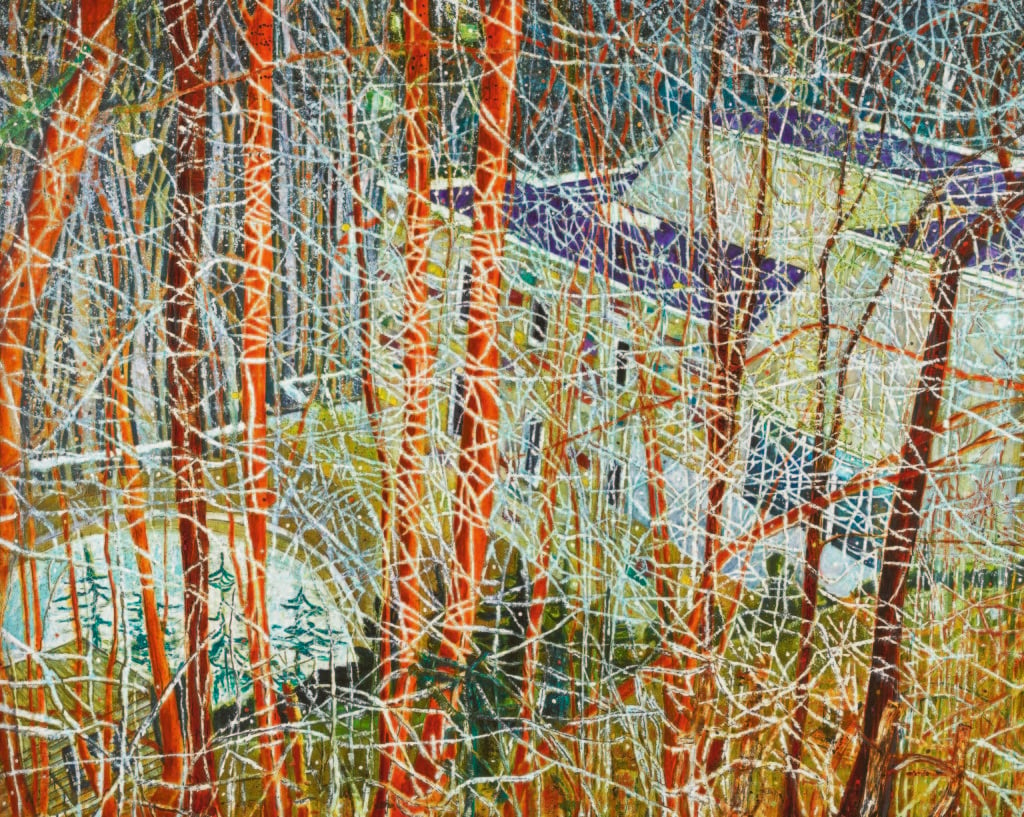

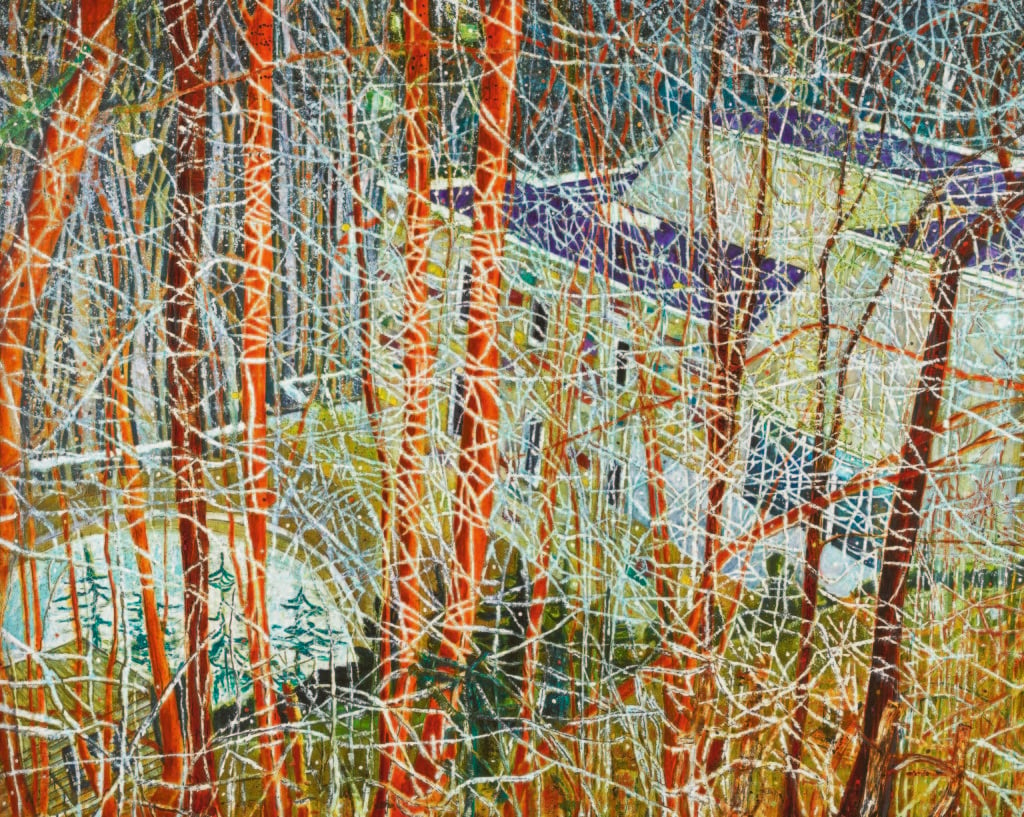

Peter Doig, The Architect’s Home in the Ravine (1991). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Compounding this trend is the fact that the market is experiencing an overall dip at the top end, where most third-party guarantees are negotiated. Sales of works priced at more than $10 million dropped by 34 percent in the first half of 2019 compared with the first six months of 2018, according to data collected by the artnet Price Database.

Paintings that have sold to their guarantors this year include Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963), which fetched $53 million at Christie’s, and Mark Bradford’s Helter Skelter II (2007), which sold for $8.5 million at Phillips.

One cautionary tale is the story behind the appearance at Gagosian’s Art Basel booth this June of Peter Doig’s The Architect’s Home in the Ravine (1991) just 15 months after it sold to its guarantor, Abdallah Chatila, at Sotheby’s for $20 million. The presentation underscored yet another reason guarantees are becoming less appealing: With a recent published auction price, it becomes difficult to make a swift profit on a resale.

Guaranteed… to Backfire?

Guarantees may also be losing their shine for auction houses, which can be left holding the bag if high-profile works subject to complex financing agreements underperform. Last year, Sotheby’s suffered losses when two guaranteed paintings failed to meet expectations.

At the house’s Impressionist and Modern evening auction in May 2018, Modigliani’s Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917) carried a lofty $150 million estimate, the largest estimate ever placed on a single work. But after several protracted—and painful—pauses by the auctioneer, it was hammered down at a below-estimate $139 million. The following month, a 1932 Picasso painting, Buste de femme de profil (Femme écrivant), fell well short of its $45 million estimate to sell for $36 million on a single bid. Both works went home with their respective guarantors.

Sotheby’s later noted that the two deals put a drag on its earnings in the second quarter of 2018. Its commission margin, it said at the time, was reduced by two factors: “a higher level of auction commission shared with consignors” and buyers’ premiums “used to offset auction guarantee shortfalls and fees incurred in respect of auction guarantee risk-sharing agreements.” In other words, Sotheby’s sacrificed some of its profit to lure top-flight works with top-flight guarantees—and was left in the hole when the paintings failed to fly at auction.

The house seems eager not to repeat its mistake. In December, the position of COO held by prominent dealmaker Adam Chinn—widely known in the industry for his outsize appetite for risk—was eliminated. At the end of the second quarter of this year, the auction house noted that its commission margins had rebounded in the absence of major money-losing deals. The strategy under the house’s new owner, Patrick Drahi, remains unclear. Although the newly private auction house will be less beholden to shareholders in its efforts to secure top lots, “no one wants to be the first person to lose money under Drahi,” one expert told us.

What Does It Mean?

As is often the case in the art market, the growing avoidance of guarantees may be as much psychological as it is driven by spreadsheets and profit margins. Bidders, some say, have become reluctant to compete against someone who already has a potentially lucrative deal in place and may have more information than other bidders heading into the sale.

“Your money goes farther than everyone else’s money” when you make a third-party guarantee, notes attorney Luke Nikas. Clients who submit such a bid often—though not always—receive a financing fee from the auction house, so if they end up owning the work, the overall cost is lower. Competitors don’t like that another bidder has such an advantage, and without competition, guarantees become a lot less profitable.

Still, not everyone sees the dip in guarantees as a red flag. Market boosters say it is simply a rosy sign of confidence in a more stable—i.e., no longer frothy—market. In a conference call with investors in May, Sotheby’s former CEO Tad Smith noted that a large number of estates and charitable organizations that had consigned work opted against a guarantee, choosing to take their chances so they would not have to share the upside with a third party. “These are very sophisticated consignors,” Smith said. “When you begin to see people saying, ‘Maybe we don’t want the guarantee,’ it’s a very interesting indicator of the health of the market.”

Looking Down the Line

Regardless of what is causing the slowdown, one thing is clear: The golden age of guarantees may be coming to an end. So what happens next?

Some observers predict that the speculators who entered the guarantee market in recent years—those whom Cynthia Sachs, the CIO of Athena Art Finance, describes as “a second tier of younger guarantors who are less seasoned and maybe taking a little more risk”—are likely to look elsewhere to make a quick buck.

For some, this is a welcome development that might make the market a bit more reflective of actual demand. Guarantees, says art advisor Todd Levin, “work like steroids do for bodybuilders, in that they artificially enlarge markets.”

Moving forward, the guarantee business may return to the smaller club of solid, seasoned players with a deep knowledge of the market—Peter Brant and those like him—who helped develop it in the first place. But if fewer works have bids in place before an auction begins, one thing is certain: The art market is about to become a lot less predictable.

A version of this story originally appeared in the fall 2019 artnet Intelligence Report. To download the full report, which has juicy details on the most bankable artists, a look at how the art market has changed over the past 30 years, and a deep dive into the market for African contemporary art, click here.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.