The Iranian art scene, like many sectors of the country, is in a state of turmoil right now, and long-held misconceptions about the region continue to plague its reputation. However, the appetite for Iranian art from collectors on the international stage is more ravenous than ever.

CAMA Gallery, a Tehran-based enterprise founded in 2015, is trying to create a bridge between the country’s art scene and the Western world. Led by co-founders Riley Frost and curator Mona Kosheghbal, the gallery represents 80 contemporary Iranian artists—40 of whom they represent exclusively—and boasts a lively exhibition program both online and in its physical gallery spaces. Earlier this year, the gallery also crossed off one of its first and biggest goals when it expanded outside of the country and opened its first international space in London.

Artnet News spoke with one of CAMA’s co-founders, Riley Frost, about his burgeoning gallery, the state of the art scene in Iran, and why art from the country is so in demand right now.

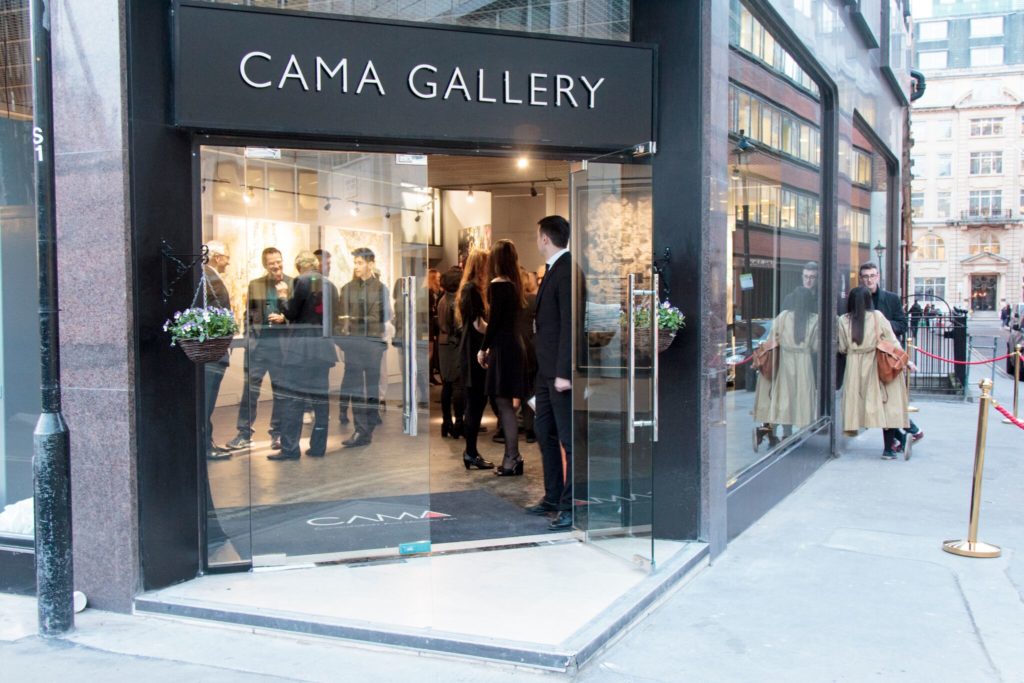

A visitor to CAMA Gallery’s new London space, looking at works by Bita Vakili and Fereydoon Omidi. Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

Can you tell me about CAMA—how the gallery was founded and how it’s structured today?

We launched the gallery in 2015. We started with a couple of spaces in Tehran, then, last October, launched an online gallery. Our biggest step happened earlier this year when we opened our landmark venue—CAMA gallery in London. That for us has been the largest hurdle; opening a gallery in London is not an easy thing to do. What we wanted to do was to provide an expansive platform so we could showcase the most eclectic mix of Iranian art—as many artists, working in as many mediums, from as many different backgrounds as possible.

Iran is a country fraught with misconception, and that is something we’re hoping to dispel through art. We consider ourselves to be an Iranian gallery in London, rather than a gallery in London representing Iranian art. That’s a key difference.

Tahereh Samadi, Untitled (2017). Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

What are some of the differences between the London gallery and the Tehran gallery?

Every local scene has its own individual nuances. The major difference occurs between the market in London and the one in Tehran. The youth behind those markets is extremely different. London, a major neo-liberal hub, is a city that runs on money. A lot of finance runs through here, and so that means that there is an intrinsic commercial value attributed to everything, be it the seats you sit in on the tube, the cars that you drive, or the artworks that you show in a gallery. In Tehran, on the other hand, the spirit is much more communal. In London or New York or any of the major world art hubs, the reason people go to openings is not only to enjoy the art, but to scope out who’s doing what and why they’re doing it, et cetera. In Tehran, the art scene is more communal. It’s grown massively over the last four or five years, exploded from maybe four galleries to well over 100, which means, that, while the market might be over-saturated, the spirit of the artistic movement in the city is very much alive.

Iranian art differs very much from that of neighboring countries or geographical regions. Iran has produced art for the last 3,000 years, so there’s been ample opportunities for different styles, mediums, and tastes to develop. Consequently, the Iranian art scene is one of the most vibrant in the world, let alone in just the Middle East. That’s what we want to bring to London. We want to bring that communal feeling to our London space. We don’t consider ourselves to be a gallery in the conventional sense; we want it to be a social space.

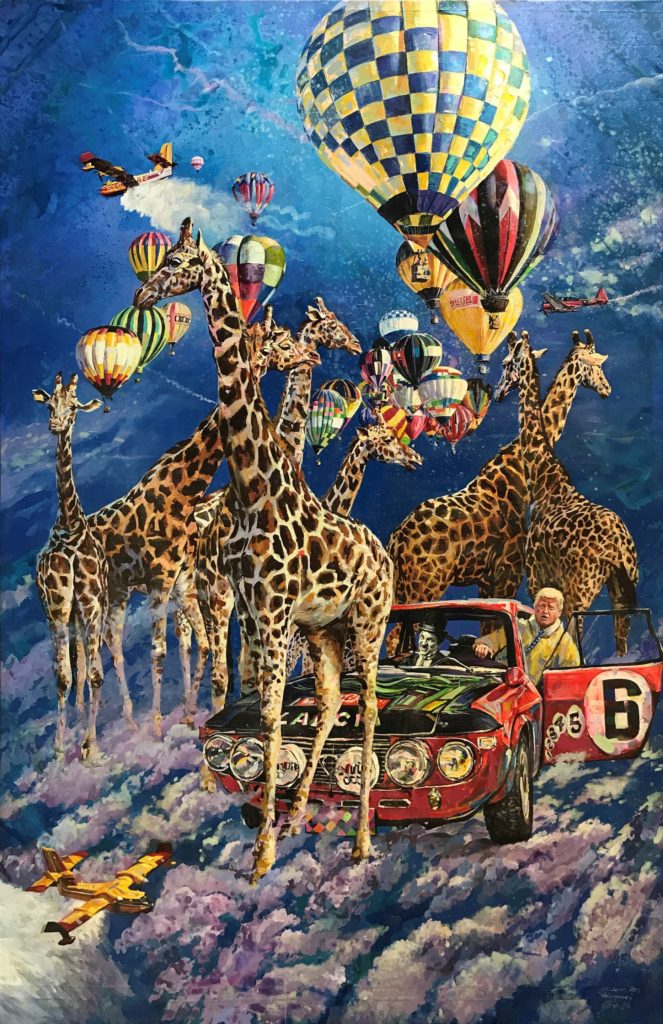

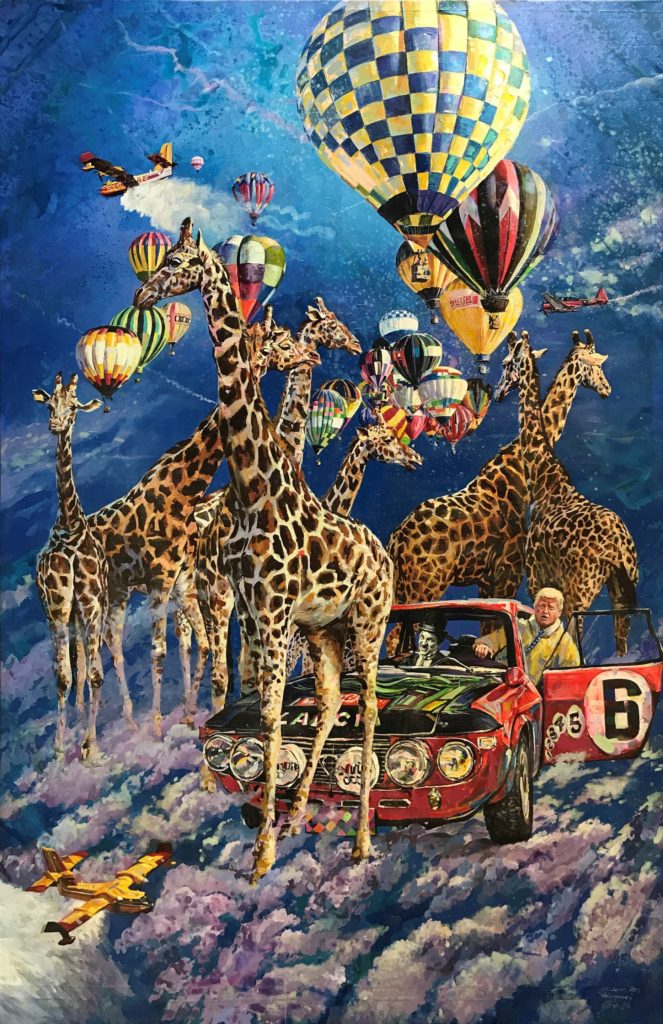

Mohsen Jamalinik, Untitled (2016). Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

Who is your primary clientele? Do you have a large base of Iranian collectors, or is it mostly Westerners?

From a commercial perspective, we are very lucky because the Persian people are hugely proud of their culture and heritage, so much so that they will actively support it financially. If you come to my house, we might sit on furniture that was designed in France, we might eat Italian food, we might listen to American music. It’s very multi-dimensional in the way that we engage with culture. Whereas with if you go to a Persian’s house, you eat Persian food, the decor is inherently Persian, the music is often Persian. They very much live their culture. So yes, we have a rather broad client base who consistently look to buy Persian works. In many respects, those clients are our bread and butter. Having said that, what we are looking to do is broaden the scope of Iranian art and educate Western collectors.

Of course, there are Iranian artists that are very well known in the Western world. But often what happens with these artists is that they are either plucked from obscurity or they move to a Western country. And understandably, they start to see that the works of theirs that are infused with a touch of Western influence will often sell better because that’s the taste of the standard Western collector. Over time, though, there’s a danger hat that sort of true, intrinsic Iranian quality is lost. Often these artists become somewhat of a hybrid masquerading under the impression that they are truly Iranian. Now, I’m not Iranian; I’m not one to question one’s legitimacy as an Iranian—that’s not my place. What I do question, however, is whether those artists are doing justice to the Iranian scene back home. Because it’s very easy to make a social commentary from afar. The artists that we work with are very much in the thick of it, and that’s who we want to present to Western collectors. And slowly but surely, that’s what is happening. When we first started, roughly 95 percent of our clients were either fully or partially Iranian. But as time has gone on, as people have become educated in the art of Iran, our clientele has diversified greatly.

Curator and CAMA Gallery co-founder Mona Kosheghbal. Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

Let’s go back to that question you posed—about Iranian artists sticking to their cultural Iranian roots rather than Westernizing your work to appeal to a larger audience. For artists, cultural authenticity is crucial, but so is reaching as wide an audience as possible. Where do you draw the line between the two?

I think it’s becoming increasingly difficult. We live in the most global society in history. That will continue to dissolve, this notion of nation-states as true borders and cultures as a bounded aspect of life. My feelings toward this used to be principally concerned with the aesthetics of art and the way that Iranians or those that have moved present their art that is very much American or Western but infused with a Persian influence. Now I think it’s more about the message that is conveyed. Most of the artists that we work with live in Iran; they breathe, work, and create in Iran. Because of that, they’re attuned to the important questions that need to be asked.

Of course, in an age when we are able to connect with people around the world in a very easy way, we have lost a lot of the nuances that fall between that connectivity, the feeling of what a culture or country is really like. I think that’s the main reason why we are keen to present artists who are inherently Iranian, who live there. The world is so fast now; things change on a second-by-second basis. You can’t keep your finger in the past. Those artists who are seen as the so-called “poster boys” of Iranian art, the specific messages that they are trying to convey is lost because they are seen primarily as symbols. We want to change that. We want to be seen as an Iranian cultural proxy.

Bita Vakili, Untitled (2018). Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions of the Iranian art scene?

I think the biggest misconception is that Iranians are Arab. Certainly, that’s true in the United States—I feel like the misconceptions there are more prominent than they are in Europe. Americans tend to blur the lines of the Middle East and the nation-states that occupy that area, bumbling them all into one. From a cultural and geopolitical perspective, Iran is hugely distinct from the rest of the Middle East.

There are a lot of misconceptions about the geopolitical situation, and an idea that all Iranian people are representative of that. A lot of my Iranian friends are far from the autocratic theocracy. Our whole ethos is showing the true side of Iran, rather than just a different side. There is a truer side to Iran that is a lot more beautiful and engaging than what is sometimes projected in the media.

Of course, we make no political statement because we’re interested in the art, but to distinguish between art, politics, and socio-cultural issues in Iran is very difficult—certainly more so than other countries because of the art scene’s protected relationship to state power. In the past, there were certain artistic freedoms that were not lent to artists as much as they are these days. When you have to live and work through that as an artist, the art that often comes out is great. “Pressure creates diamonds” in the phrase that I like to use; I think it’s indicative of the Iranian scene.

Adel Younesi, Untitled (2016). Courtesy of CAMA Gallery.

The country is in the midst of turmoil right now. How has that impacted local artists and the work they’re creating?

I feel like the effects can only be negative in many respects. From a monetary perspective, there have been problems in Iran for quite some time, and they have increased over the last few months. A lot of people simply don’t have the financial freedom to make art. Additionally, Iran is not connected to the international banking system, so a lot of wealthy Iranians—those that support the artists—have seen their net worth devalued huge amounts over the last few years—especially over the last six months—because most of their wealth is held in Iranian currency. As these sanctions are further imposed, it’s going to continue to impact collectors’ capacity to support the art scene. There’s just no way of looking positively at it. The currency crisis is unfortunate, but the sanctions that are going to be enacted—or have already been enacted—could be the real problem for the Iranian art scene. There will still be vibrant Iranian art for years and years to come, but it’s those interesting artists who look to push the boundaries, whose work isn’t necessarily so commercial, that will lose out.

At the moment, the gallery system around the world is changing. I feel like it is time for things to be put more towards the artists rather than the dealers. With Iranian art, it’s our duty to represent them in the most correct manner. To put it into context, we work with 80 artists, and 40 of those are signed exclusively with us because they know that we are going to represent them in the most legitimate, proper manner and respect their artistic principles while also representing them well on the commercial level.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.