Art World

5 Must-See Artists at the Rencontres d’Arles, the ‘Venice Biennale of the Photography World’

From Patrick Willocq to Gilbert & George, here's what you won't want to miss at the prestigious summer photo festival.

From Patrick Willocq to Gilbert & George, here's what you won't want to miss at the prestigious summer photo festival.

Few places have quite the charm of Arles, a small town in the South of France where the 49th edition of the summer photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles is now in full swing. Even the facades of the shuttered yellow houses that line the town’s cobbled streets—immortalized in Vincent Van Gogh’s 1888 painting Café Terrace at Night—are adorned with works of art as part of the festival, which some consider the Venice Biennale of the photography world.

Installations, events, and photography displays spill in and out of the town’s historic buildings during the course of the festival, which runs through September 23. In Arles, vastly different approaches to the medium, from photojournalism to fine art photography and beyond, blend with the architecture at some 40 venues, including ancient Roman ruins (the small town was once a capital of Constantine’s empire), medieval cloisters and chapels, 19th-century industrial workshops, and the modern-day Monoprix supermarket.

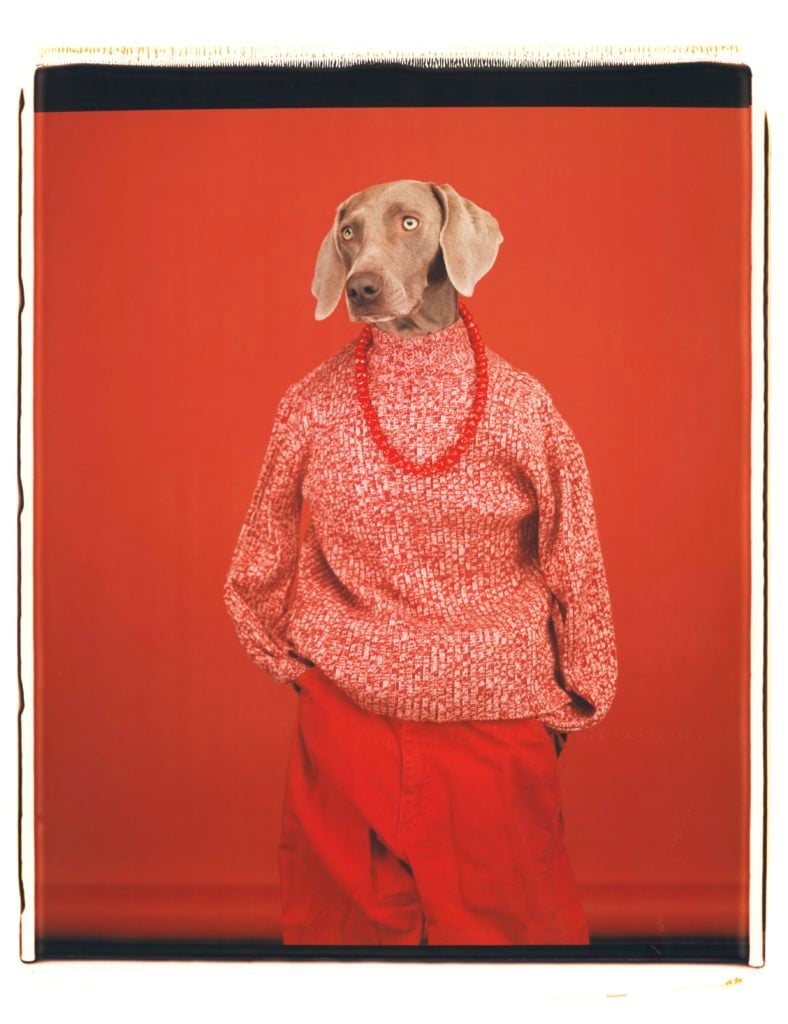

The atmosphere is alive with excited chatter as tanned, rosé-quaffing audiences exchange opinions on everything from Adel Abdessemed’s harrowing mammoth ivory sculpture of the iconic Vietnam-era Napalm Girl photo to William Wegman’s playfully human-esque photo portraits of his beloved Weimaraners.

Last night, in the ruins of a Roman-era open air theater, festival director Sam Stourdzé led a “happy birthday” chorus for the veteran photographer William Klein. In the background played a film tribute to the 90-year-old Frenchman who famously captured the tireless showmanship of Muhammad Ali in his 1974 film portrait of the prizefighter.

Another birthday was celebrated by the Prix Pictet, the 10-year-old photography prize dedicated to documenting issues of sustainability. The work of all the previous prize laureates is being revisited in a major retrospective in the Crosière venue across town. Previous themes for the prize have included “water” and “earth,” but the Prix Pictet is taking a slightly different approach to its 2019 theme: Hope.

Looking across the festival, the new theme resonates. After years of bleaker offerings at the festival, and in the prestigious prize, there is a more optimistic mood at many of the exhibitions in town. In that spirit, here are five of our favorite photographers to encounter at Les Rencontres d’Arles,

Patrick Willocq, The Bridge Between Peoples. Courtesy of the artist.

The small southwestern French town of Saint Martory has just 1,000 residents, 50 of whom have migrated there recently as asylum seekers. For his project at the Manuel Rivera-Ortiz Foundation, Willocq immersed himself in Saint Martory for five months, getting to know the migrants who came from as far as Chad, Bangladesh, and Ukraine, as well as the native townspeople, who are by turns receptive and hostile to the foreigners.

Willocq creates painstakingly elaborate sets—which almost appear photoshopped, but aren’t—on which to stage striking narrative tableaux, cast with local people. The photos demonstrate how people and places adapt to change, and remind us that many of the native Saint Martorians themselves once came to France as Spanish migrants. One set of photos shows a traditional French lunch scene disturbed by migrants literally parachuting into the town. Next to it, the same scene is depicted a year later, with the new inhabitants now integrated into it, sharing the lunch table.

Robert Frank, Bus-Stop, Detroit (1955). Collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur. Gift of the artist.

In a windowless room on the ground floor of the former 19th-century asylum where Van Gogh briefly lived after cutting off his ear is an exhibition devoted to the Swiss photographer Robert Frank.

The 85 prints published in Frank’s groundbreaking 1958 photo-book The Americans are well known. Here, though, unknown shots from the series Frank made while traveling across the US on an epic roadtrip, paid for with his Guggenheim Fellowship, are displayed alongside other works from his travels to South America and Europe.

These photographs, many of which are unpublished, chart a rising sense of boredom and unease amid rampant consumerism and injustice in the first half of the 1950s. The striking photographs offer a glimpse of a slowly percolating sense of agitation in the years leading up to the Civil Rights movement.

Jonas Bendiksen, Moses Hlongwane, otherwise known as “Jesus,” giving a sermon during his wedding to Angel, one of his disciples. In Moses’s theology, his wedding day was the start of the End of Days. South Africa, 2016. Courtesy of Jonas Bendiksen/Magnum Photos.

In a 17th-century church opposite the town’s cathedral, Magnum photographer Jonas Bendiksen presents an exhibition of photography, found objects, and scripture that tells the stories of seven men around the world who all believe they are the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, as prophesied in the penultimate verse of the New Testament, “Surely I am coming back soon.”

Bendiksen visited the various communities of these men and their followings in England, Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Zambia, Japan, and the Philippines and documented their daily rituals and beliefs. His subjects range from small-time cult leaders with a handful of followers, such as David Shayler (and his alter-ego Dolores) to the more influential, including Apollo Quiboloy, whose megachurch empire in the Philippines has a six-million-strong following. The disciples are connected by a common thread: hope for salvation.

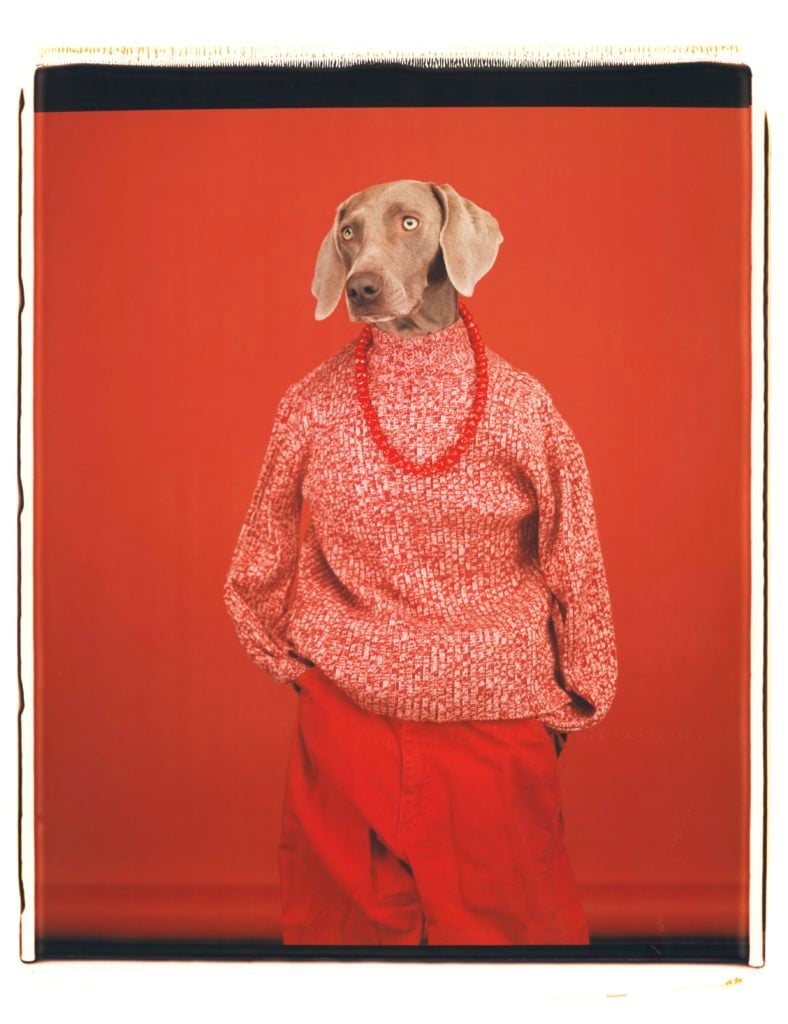

Gilbert & George, BENT SHIT CUNT (1977). Courtesy of Gilbert & George.

A trip to Arles wouldn’t be complete without a visit to check in on the progress of Maja Hoffman’s Luma Foundation, instantly recognizable on the Arles skyline by its glittering 200-foot-tall Frank Gehry-designed building. Next to it is the 10-acre Parc des Ateliers, an exhibition space being constructed inside a former industrial railyard, slated for completion in 2020.

While construction on the rest of the site is ongoing, the artist duo Gilbert and George have taken over Luma’s Mécanique Générale and Grande Halle with an epically scaled retrospective. The idiosyncratic pair, who have been working together for 50 years, spoke of the hostility some of their early work, which used “dirty” words and graphic depictions of sexuality, received from both straight and gay communities. Some members of the gay community were offended by their 1977 work Queer, for example, but it can be given a retroactive reading of hopefulness: The work was an early attempt to reclaim the word from its original derogatory intent. Just a few years later, they say, the same people offended by their use of the term were walking around wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the phrase “Queer as fuck.”

Marcelo Brodsky, Paris, 1968. Courtesy of the artist, Henrique Faria Fine Art, New York & Rolf Art Gallery, Buenos Aires.

Across France, the revolutionary spirit of May 1968 is alive as the country marks 50 years since the historic uprising, which began with student protests in Paris but quickly spread to a citywide general strike. Society was young; the baby-boomers had reached adolescence, and were becoming disaffected with the social mores and values of their elders. Meanwhile, the US was embroiled in the Vietnam War, China was in the midst of its “Cultural Revolution,” and the Soviet Union was invading Prague. The youth figured something had to give.

In a show titled “1968, What a Story!,” archival photos and text-based works by the Argentine artist and activist Marcelo Brodsky appear alongside historical photos of hastily erected barricades, magazine covers, and transcriptions of radio communications between an outnumbered and increasingly desperate police force throughout the period of civil unrest.

The images of this generation of activists, paired with Brodsky’s lyrical interventions, remind viewers of the possibilities that are created when young people come together to drive forward social change. The show can’t help but conjure a sense of today’s atmosphere, with its mass movements such as Black Lives Matter, and the global women’s marches declaring “time’s up” on another era of unquestioned social norms.