This year marks the 20th anniversary of “The First Cyberfeminist International,” a meeting that took place at Documenta X in 1997. This month, a five-day conference at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art titled “Post-Cyberfeminist International” revisited those issues and updated them for the times, giving rise to a new movement known, appropriately enough, as post-Cyberfeminism.

So who are these post-Cyberfeminist artists and what theories are they engaging with today? To find out, we first have to know what Cyberfeminism was and how it became post-Cyberfeminism, if that is indeed where we are today. Here we offer a few notes on the history of the movement and where it’s gone in 2017.

Cyberfeminism is undefined—by definition.

The term was first coined in the early 1990s, but the source remains unclear. Most attribute the word to either Sadie Plant, director of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at the University of Warwick, or to the VNX Matrix, an Australian artist collective that penned The Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century in 1991. (“We are the virus of the new world disorder,” the manifesto reads, “rupturing the symbolic from within saboteurs of big daddy mainframe.”)

During The First Cyberfeminist International, the Old Boys Network—an international coalition of Cyberfeminists established in 1997 in Berlin—agreed to intentionally keep the term undefined in order to keep things as “open as possible as consensual.”

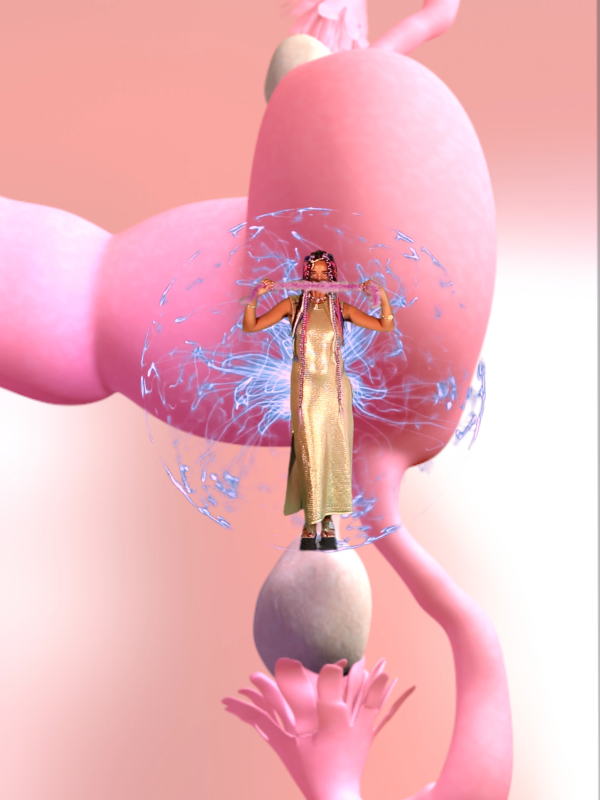

Mary Maggic, Molecular Queering Agency (2017). Image courtesy of Mark Blower and the artist.

Still, some have offered their own personal definitions. “For me, Cyberfeminism was an artistic experiment of testing contemporary forms of organization,” the Berlin-based artist Cornelia Sollfrank—a founding member of the Old Boys Network—told artnet News. “It was a child of its time, inspired by all the new and yet unexplored opportunities of digital networked technologies.”

Sadie Plant wrote that Cyberfeminism describes “the work of feminists interested in theorizing, critiquing, and exploiting the Internet, cyberspace, and new-media technologies in general.”

Who are Cyberfeminists?

Donna Haraway—the theorist, feminist, and author of the 1984 book A Cyborg Manifesto—is often cited as the original inspiration for the Cyberfeminist movement. Other artists associated with it include Faith Wilding, Cornelia Sollfrank, Linda Dement, Melinda Packham, and Shu Lea Cheang, whose 1998 web project Brandon was the Guggenheim Museum’s first foray into collecting Internet-based art.

Cornelia Sollfrank. Image courtesy of the artist.

Enter post-Cyberfeminism.

When (and why) did Cyberfeminism become post-Cyberfeminism? In short, Cyberfeminism was no longer cutting it when it came to the most urgent issues in the digital sphere, like “sexual harassment via social media to privacy and the protection of images online,” wrote Helen Hester in her 2017 essay, “After the Future: N Hypotheses of Post-Cyber Feminism,” a text that was frequently, and heatedly, referenced at this month’s gathering in London.

Discussing the supposed fall of Cyberfeminism within contemporary art, Hester argues that the term “cyber” has lost its luster due to an association with the domestication of the digital. Since Cyberfeminism was in dire need of an update, some started adopting the terms post-Cyberfeminism and Cyberfeminism 2.0.

Who are the artists working in this field today? The 2016 film The Flavor Genome by Anicka Yi, last year’s winner of the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize, was screened at the “Post-Cyberfeminist International,” alongside presentations by artists Mary Maggic and Cornelia Sollfrank, Salome Asega, Ain Bailey, Anaïs Duplan, Caspar Heinemann, shawné michaelain holloway, Zarina Muhammad, E. Jane, Jenn Nkiru, Tabita Rezaire, and Zadie Xa. Also involved is writer and curator Legacy Russell, who organized the #Glitchfeminism portion of the ICA’s program.

Zadie Xa, Mood Rings 2 (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

Post-Cyberfeminism relies on artists at the margins.

“It was important for me to participate in the Post-Cyberfeminist International precisely because I think it’s very important as women and gender-nonconforming folk to create these discourses with artists who came before you,” said Victoria Sin, a London-based artist who was a prominent participant in the “Post-Cyberfeminism International.”

“The history of feminist art and Cyberfeminism is often not taught in curriculums and it’s often up to artists on the margins to make links in our own discourses so that we are not complicit in the erasure of histories of resistance,” Sin said.

Sin’s ongoing video and performance series, Narrative Reflections on Looking, addresses “the experience of identifying with images, and power dynamics in looking—it is about taking on images in an image-based culture.” One way Sin does that is by “questioning the construction and reification of ideal images of femininity.”

Victoria Sin, Narrative Reflections on Looking (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

Post-Cyberfeminism checks technological abuses of power.

“What is urgent about re-visiting Cyberfeminism is the fact that the social and political conditions have dramatically changed over the course of the last 20 years,” Sollfrank said.

While society has witnessed the rapid-fire spread of hashtags like #metoo and #notsurprised as examples of digital tools being harnessed for women’s empowerment, there have been enormous technological disadvantages as well.

“Now we know more about the downsides of networked technologies; we had to learn how they are being abused by corporate and governmental interests in order to surveil and control users and citizens,” Sollfrank said. “This situation continuously needs to be confronted with feminist methodologies of analyzing power structures and one’s own potential and agency within.”