Artists-in-residence programs have become popular at institutions ranging from Google to CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Now, they are coming to government agencies, too. Next month, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office will become the first agency associated with law enforcement to launch an artist-in-residence program. James “Yaya” Hough, the artist chosen for the job, will be tasked with introducing a fresh dose of creative thinking to the 600-member staff—with a side of empathy.

Hough, a Pittsburgh resident in the process of relocating to Philadelphia, might seem an unlikely candidate at first. He was released from a state prison in Graterford, Pennsylvania just last August after serving 27 years for a murder that he committed at age 17.

It was in prison that he was introduced to Mural Arts Philadelphia, a non-profit organization that works with at-risk teens, as well as current and former inmates, “to create art that transforms public spaces and individual lives,” according to its mission statement. It was Mural Arts Philadelphia, in concert with the Los Angeles-based organization Fair and Just Prosecution, that developed the concept of establishing an artist-in-residence program at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office: a six- to nine-month project, with its initial $25,000 budget funded by the Agnes Gund-sponsored group Art for Justice.

Hough, in his role as artist-in-residence, won’t be creating paintings or sculptures. The goal of the program is more in line with social practice art: to initiate conversations about the need for criminal justice reform, with an artist as moderator and interlocutor. “My presence in the prosecutor’s office sends a message to district attorneys, a powerful symbol of hope and redemption,” Hough said in an interview with Artnet News.

Through the program, prosecutors, victims and survivors of crime, and former convicted criminals will all take part in workshops, seminars, and other initiatives. The program is the latest in a string of initiatives across the local, state, and federal government that aim to spark new thinking by inviting an artist in to shake things up.

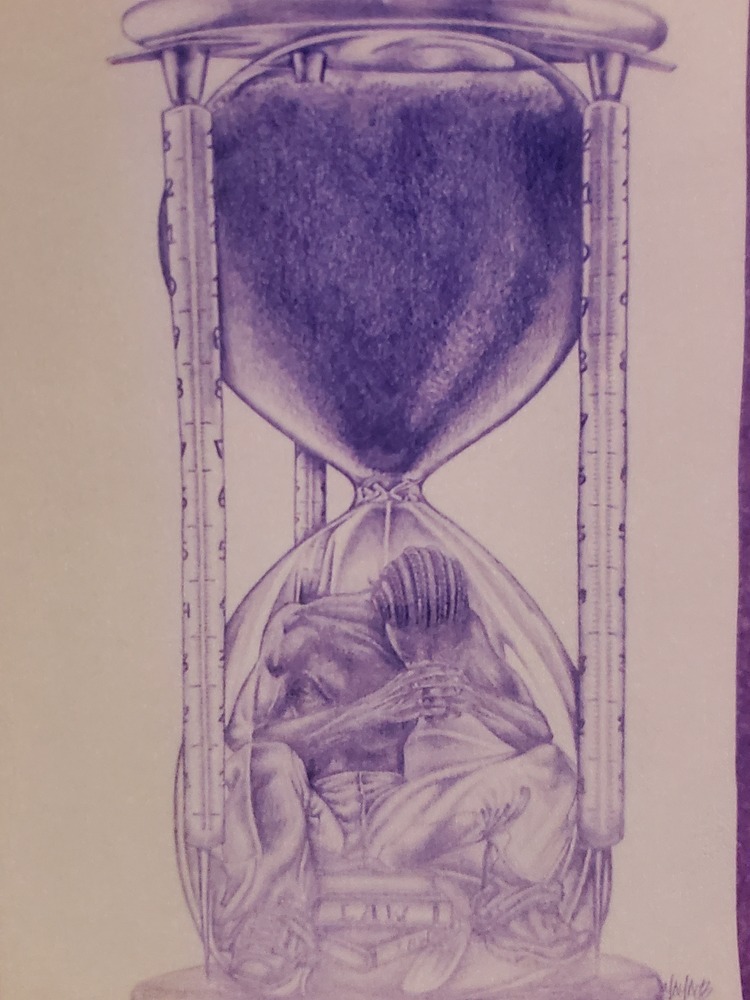

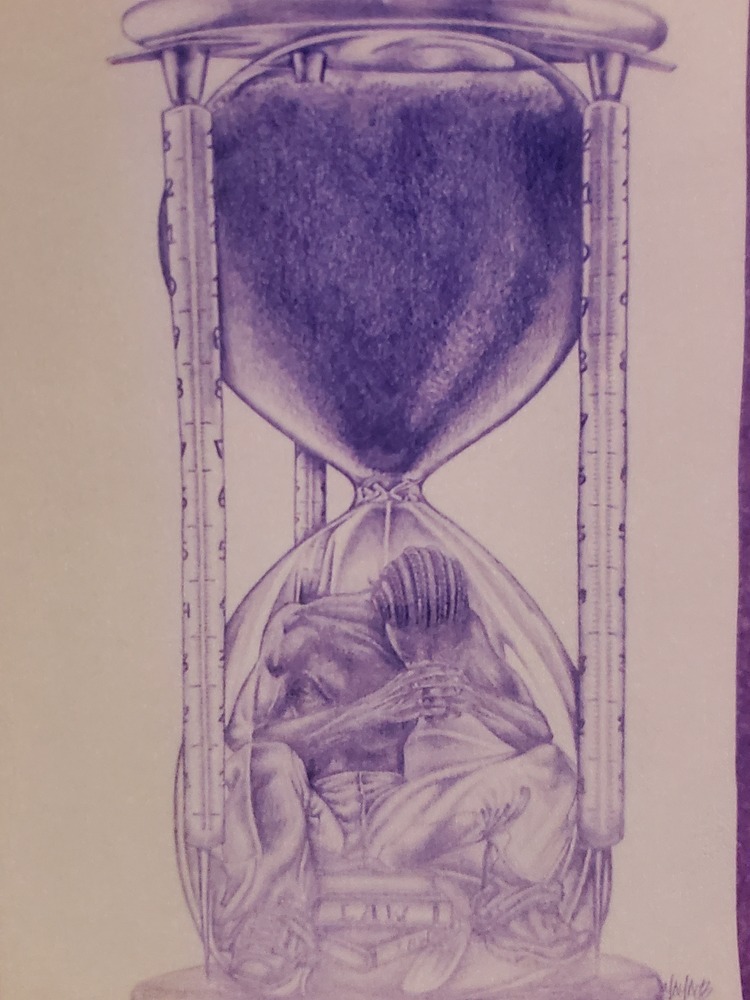

An untitled drawing by James “Yaya” Hough.

“I came up with the idea because few vehicles are as impactful as art in changing hearts and minds,” said Miriam Aroni Krinsky, founder and executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution. “Through an artist-in-residence program, we can use the clout of art to point up the damage that the criminal justice system has done.”

She proposed the idea of setting this first-in-the-country program in the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office because Larry Krasner, who became the district attorney there in 2018, has been an advocate for “shrinking the criminal justice system, ending the death penalty, [and] reexamining previous convictions and decades-long sentences.”

Mural Arts Philadelphia proposed Hough for the program, having worked with him as part of its prison arts program over a 20-year period. “James was interested in drawing but, through us, he learned how to draw,” said Jane Golden, founder and executive director of Mural Arts. She finds him uniquely qualified for the artist-in-residency gig due not only to his artistic skill, but because “he is deeply empathic… he understands the criminal justice system, and he articulates what he went through so well.”

A Fortuitous Series of Events

Two unrelated, monumental events helped create the possibility for this radical artist-in-residence program in Philadelphia. The first was a ruling by the United States Supreme Court in 2012 that found that sentences of life without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional for juvenile offenders, a judgment that was expanded by the high court in a similar case four years later. Those rulings helped lead to an early release for Hough, who had himself been sentenced to life without parole.

The second was art collector Agnes Gund’s private sale, in early 2017, of Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece (1962) for $165 million (the buyer reportedly was billionaire hedge-fund manager and art collector Steve Cohen.) Gund used $100 million from that sale to start up the Art for Justice Fund, which provides grants to organizations seeking to make visible the human dimension of mass incarceration—informing the public about mass incarceration and its links to racial bias and increasing educational and employment options for those leaving prison.

The art patron Agnes Gund. Photo by Annie Leibovitz.

“When a prosecutor charges a defendant, when a judge sentences a defendant, they never see the transformation of that individual taking place while incarcerated,” Hough said. “They don’t see that someone can become a creating, contributing member of society. Prosecutors have the ability to crush offenders, but they can use those same powers to encourage offenders to do right and be redeemed.”

Hough’s work at the district attorney’s office will involve more than just conversations and workshops. He plans to create a series of three-minute videos—“like a long-form commercial”—based on feedback from participants in the workshops and seminars, incorporating drawings he’ll make of those who took part. These videos will be shown at the district attorney’s office, on social media, and at the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

Since news of the program began circulating, Krinsky said she has “heard from other DA offices”—one in California and one in Texas—“who want to work on this model.”

Artists in Government?

DA offices aren’t the only ones pursuing the artist-in-residence model. Others have been going on for years, with success for both the host and the artist. The National Park Service brings in one artist at a time for a period of between two and five weeks. Residents are required to donate a piece of art that represents their stay to the Park Service’s collection, and they also may be asked to present a talk for park visitors.

“I just loved it,” said Kim Henkel, a metal sculptor in Denver, Colorado, who had been a resident at Mt. Rushmore, the Grand Canyon (“I was in a beautiful apartment overlooking the south rim”), and the Petrified Forest between 2007 and 2009, spending one or two months at each site.

All five branches of the US Military also bring in artists—known as “combat” artists—for short-term (usually, a week or two at most) residencies on military bases or other locations where soldiers are stationed. The work they make on site is donated by the artists to the collections maintained by the respective branches.

The military doesn’t commission artists or pay them for their work, only offering them round-trip transportation, officers’ quarters, and food. Artists do receive a temporary rank as captain or colonel or major, depending on the particular service (the artists aren’t able to give orders to anybody, but they can get first in line at mess time). Military artists-in-residence are not told what or how to paint; they are not asked to be propagandists. Some of the artworks made in the past have focused on scenes that aren’t heroic or dramatic, including bored soldiers drifting off to sleep.

Many artists take part in these military programs just for the thrill of it. William Phillips, an artist in Ashland, Oregon whose specialty is aviation art, lights up when he talks about visiting an Air Force base, especially when describing taking a ride in a fighter jet: “Every time you get into a high-performance aircraft, you face danger. It’s not like sitting in my studio. And, when you put on that flight suit…”

Maxx Moses with his mural-painting team in Zimbabwe.

The US Department of State has its own residency program for artists too, called Arts Envoy. It brings performers, writers, and visual artists to countries all over the world, where they may work with local groups for between five days and six weeks. Maxx Moses, a 57-year-old muralist and street artist living in San Diego, worked for a week in the city of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, in 2011. His expenses, from transportation and accommodations to food and materials, were paid for by the State Department. Moses led a team of 10 local artists in creating a series of murals on the theme of combating the AIDS epidemic. “Most of the artists had never worked with spray paint before or created in front of a live audience,” he said.

And of course, perhaps the longest-running and most fabled artist-in-residence is Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who creates what she calls “maintenance art.” Since 1977, Ukeles has been the unsalaried artist-in-residence of the New York City Department of Sanitation. Among her artworks are a choreographed ballet of backhoes titled Romeo and Juliet and Touch Sanitation, an endurance performance that involved shaking hands with all 8,500 workers in the sanitation department while saying, simply, “thank you.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.