Art World

‘This Year Has Deranged My Senses’: 12 Artists on How the Pandemic Has Changed the Way They Approach Their Work

All of a sudden, artists had to recalibrate to new realities of scale, staff, and sensory experiences.

All of a sudden, artists had to recalibrate to new realities of scale, staff, and sensory experiences.

Today marks the one-year anniversary of the day the World Health Organization declared the spread of the coronavirus a pandemic. Since then, more than 2.5 million lives have been lost around the world and nearly everyone has been affected in one way or another.

In the art world, gallery closures, exhibition cancellations, and income losses have taken tangible and psychological tolls on artists—and all of it is coming out in their work. To find out how the pandemic has altered their artistic practices—for better and worse—we checked in with 12 artists to hear about the past year in their own words.

I am in my studio working during the pandemic lockdown. Sometime back in April 2020 the forces pushing at society and health were at the highest degree of insanity. We had an out-of-order president who had nothing to offer but false information. We couldn’t see our loved ones and had no degree of insight as to what to do but hope that within ourselves we could find the peace of mind to get through it. I had only one way, which was to paint my “distant figure paintings.”

Samson Young’s Sonata for smoke (2020, revised 2021) production still. Photo: Dennis Man Wing Leung.

I’ve been mostly working on my own during this time. I’ve been making small drawings more regularly than before. I experienced one exhibition-related quarantine, and I am never doing that again. I’ve gotten used to setting up exhibitions remotely now. I was surprised that it wasn’t difficult, even for works with technical elements. I also know some artists who operate remotely by choice, but I am feeling isolated and I miss the physical connection.

Right before the pandemic hit I had just started over with my work. I was tired of my drawings, of my narratives; I was ready to go toward—and back to—painting.

I’ve been lucky enough to keep my side gigs consistently throughout the past 12 months, and therefore I’ve been privileged enough to focus on observing the frozen, scary, and unstable state of things—and to try to help, when possible.

But even though my life has maintained a certain rhythm, the more dramatic the situation has become in the real world, the more my studio has assumed the features of a place for uncanny, existential, and imaginative practices. Something has changed for good in the way I paint and see; I found my colors.

Alvaro Barrington, They have They Cant, (2021). © Alvaro Barrington. Photo: Charles Duprat, courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac, London, Paris, Salzburg.

Sometime in early fall, when we were facing a new potential lockdown, my homegirl told me she was gonna delete her dating apps, get some sexy underwear, a bottle of wine, light some candles, and take a bath. It wasn’t for anyone else, it was for her. Normally, during pre-holiday “cuffing season,” a lot of folks I know would be looking for a relationship. Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s, Valentine’s Day, they are all around the corner. Folks suffer tremendously from the impact of Covid—I think particularly of young children and parents who have lost their jobs, and the stress that causes in any household. So many of us define our worth by our labor under capitalism. Parents define themselves by their ability to provide and, for many, that was taken away without any safety net, through no fault of their own. They are powerless, stuck at home watching their children struggle with bad internet and a shitting computer. There are generational scars being overextended to many folks and in particular to women and people of color and the youth’s new scars are being formed right now. I can’t imagine that journey to healing… Anyway, a lot of folks I know have used the last year to work on themselves, work on their demons, become better at something they were interested in, like art, yoga, music or DJing, and learn to take better care of their bodies. I have found inspiration in my friends and family and I’ve decided that I need to creatively translate this era of isolation, but also celebrate those who have worked on themselves.

The pandemic has made me address something that I think I had ignorantly tried to pretend I was too old to think about as I’m nearly 40 and remember landlines. I’m speaking about the digital revolution. If the industrial revolution made the camera an accessible object that impacted painting. The digital revolution will affect painting in ways hard to imagine now. I deeply believe painting with its long history can add much to the digital the way it added to film (think about 1920s collage art to the Adobe cut-and-paste feature). I formed a collective with some friends like Hazel Brill and Dorus Tossijn and we have been brainstorming how to engage more radically with the digital. There is a very important David Bowie clip where he is talking about the potential of the internet that I find gives me so much life.

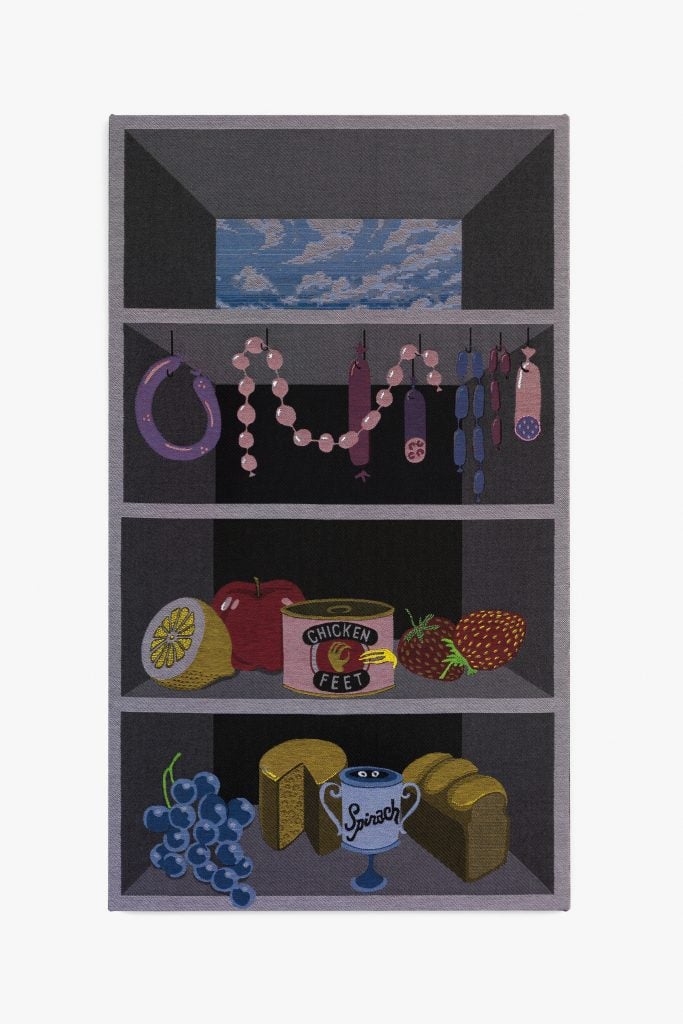

Oona Brangam-Snell, Day 71 (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Mrs., New York.

This past year in New York City has deranged my senses—the walls are caving in, so I lamely leave my house each day and try to have one benign interaction with the outside. Isolation can be weirdly overstimulating, so I began to crave simplicity and quiet, which crept into my work and pushed me to leave these longer pauses in the form of blank space. When I was sketching Day 71 I was trying to fill in every inch of shelving and then felt compelled to flip that dark vaulted interior into a moment of flight instead.

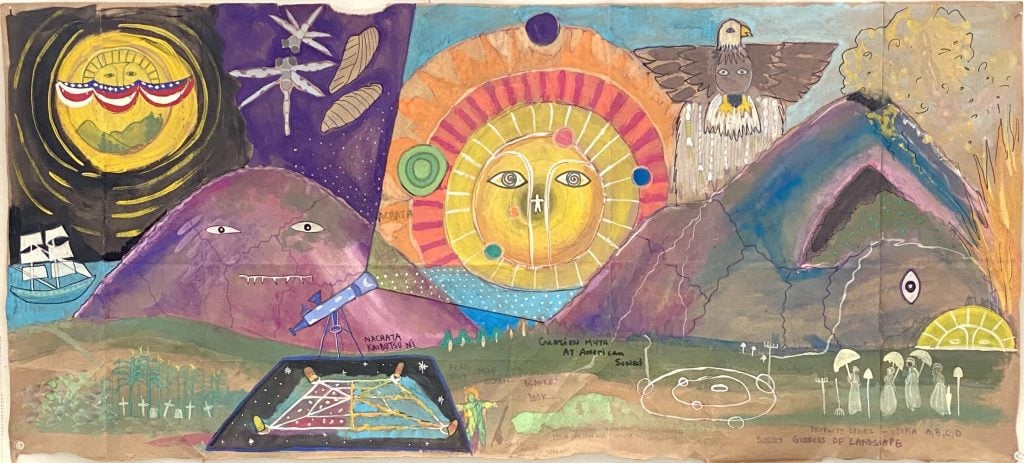

Firelei Báez, Untitled (A Correct Chart of Hispaniola with the Windward Passage) 2020. Photo by Dan Bradica, courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York.

COVID has felt uncomfortable, disturbing, and extremely normal all at once. Normal in the sense that, as a visual artist, “social distancing” and the use of PPE, such as masks and gloves were a regular thing in my studio. And the workload has been as intensive as ever. For me, COVID has not necessarily involved time to try out nice baked bread recipes, or to learn a new craft. Instead, I’ve had time to learn and try out new methods and materials, different ways of conceptualizing the figures that I’ve been working on for years. What I’ve developed during this time are many kooky experiments that will need some loving before they see the light of day. I keep having to remind myself that the world is in flames, so the only normal thing to do would be to rest. I know I should rest. But it seems like every month an exciting opportunity comes up.

Something challenging, given social distancing and quarantine, was finding new ways of filtering all the visual media that became a vital link to the world outside. I syncretized all that information into paintings of figures at rest. While I’ve been focused on work during this time, I’ve given the figures in my new paintings that promise of rest, and the knowledge that it is a regenerative tool. An example of this is On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us) (2020), from which a detail was used for the Public Art Fund summer bus-shelter campaign. The painting is of a woman of color resplendently at rest, on a sunny grassy field, reading a book from Octavia Butler’s Earthseed series. It came after looking at several posts by the wonderful Instagram page The Nap Ministry, reminding us how our ancestors of color had to strategize for, and carve out space for, rest outside of oppressive systems. This was specially highlighted this past year as the major labor and death burden of COVID-19 has fallen on people of color.

Many images of protest last year were vitally, energetically connective, especially after George Floyd’s death. Many of us wanted to make sure to elucidate how these protests exist in continuum with movements across centuries and geographies. One particular image that struck me was of civil rights activists, Freedom Riders specifically, at rest in a church. This intergenerational, beautiful image of women sleeping in church pews, a regenerative pause in-between protest. So, this figure in my painting becomes an amalgamation of all that information, the knowledge, the surety that along with facing the raging fires outside, there is an absolute need to pause, to rest and regenerate yourself. I feel strongly that it is equally important to know when to create space for others to do so, also.

I am in the lucky space of being healthy and able to immerse myself in a practice that revels in solitude. I hope these images I have made will give space for rest to someone else. To create room for a pause, a breath for the viewer.

The isolation and solitude let me think big. I have been working with large cloud forms for a couple of years now, and was focused on how clouds reflect weather, a force that affects us all. The pandemic drove home how connected we are as a species, even if we don’t always feel that way. Covid pushed me to think even more broadly, not just about my cloud sculptures, but all the work that I do and have ever done—and its impact on the planet. I decided to make my work not just sustainable, but carbon-negative.

The experience of lockdown did not change my practice much logistically as I tend to make smaller, more intimate works that I create myself in a solitary manner. However, the pandemic has been formative for my personal and spiritual journey, and that has directly affected my current series, “Nomi.” I have been exploring grief and trauma within the home for some years, but the conditions of 2020 taught me that there exists within me, and within us all, a force of power, freedom, creativity, and joy that is constant and unchanged by our external conditions and experiences. I gave that force a name and persona. “Nomi” is currently on view at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London, via their online viewing room.

Joana Vasconcelos, Pop Galo (2016). ©Luís Vasconcelos, Courtesy Unidade Infinita Projectos.

The pandemic has deeply affected the art world and, upon returning home from the opening of my show “Beyond” at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, I was deeply saddened to have had to close my studio for the very first time in over 25 years and send all my team home. It was a huge challenge, which we do our best to overcome on a daily basis, and even working remotely we’ve managed to develop proposals, new projects, and plan life after confinement. Being used to thinking in big-scale sculptures, I reverted to drawing, which proved once again a great way to focus and think. Doing yoga, meditation, regular meetings, online workshops, we found the strength to plan ahead. With the certainty that art remains a source of inspiration and strength for the future. No matter what happens, art continues to thrive as it thrives from within ourselves.

A view inside Giovanni García-Fenech’s studio in March 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

The first thing that happened was that my scale shrank. Already in March I found myself floundering in front of large canvases, so I started working on small compositions. By June, disgusted by the Trump administration’s utter disregard for human life, my abstractions turned into death’s heads. I had always avoided painting skulls as too clichéd, but now it felt warranted. And I’m still painting them.

Saya Woolfalk, We Emerge from the Sunset of Your Ideology (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme.

To be honest, at the beginning of the pandemic the anxiety almost crippled every aspect of our life here in New York but as we got back into trying to have some semblance of routine for the sake of going on, we decided to slow down and to let go. In many ways, we feel it has been a time to try to shift the way we relate to making work, but also to ourselves as people and to our communities. Many things that seemed significant before seem irrelevant to us now.

We have always been working in our studio, so in some ways the rhythms of our daily practice are the same. We were also doing things online for many years and have been working on a project that provided a lot of solace in some of the hardest moments. But at the same time a big part of our practice was being out in the world doing research, speaking with people, filming in common spaces, collaborating with others. We also used to do live performances. One of us had started DJing and we would spend a lot of time at our friends gigs. These were all things that were such a vital part of our practice and lives. Their absence has been very difficult. For our latest project we are collaborating with musicians in Palestine and we have been trying to get back to work and film with them for the past year. So far only one of us has been able to make it back. This isolation from the communities we feel a part of has been the most difficult thing for our practice and for us as people. We suppose in some way we have responded to this by starting an expanded publishing project, Bilnae’s, which supports and publishes work from other young artists, writers, and musicians. We launched our first album in November by Dakn, an incredible musician and MC from Palestine.