Image: courtesy VW (Veneklasen / Werner) Berlin

Zheng Guogu My Teacher (1993)

Image: courtesy VW (Veneklasen / Werner) Berlin

Chinese artist Zheng Guogu is hard to pin down. Working in a variety of media, his versatile practice is characterized by a thematic approach rather than a signature style. Zheng’s complex vision of a world in constant flux is, on the one hand, informed by an intimate knowledge of traditional Buddhist and Daoist art, while on the other hand reflecting on the rapid changes brought on by technology and societal transformations in China.

Zheng, who’s shown at numerous international exhibitions including the 50th Venice Biennale and the 2007 Documenta, hails from Yangjiang, in China’s southwestern Guangdong province.

He was a founding member of the Yangjiang Group, together with Chen Zaiyan, and Sun Qinglin, who regarded art as being about social action in everyday life, and pushed for a new practice of calligraphy—along with shopping, football, gambling, drinking, and eating—in contemporary art.

In the last few years, Zheng has shifted his focus from means of conviviality (which included, for him, heavy drinking as well) and towards a research of underlying energies, that is closely linked to Buddhism. To cleanse the space and prepare the viewers for the exhibition of his new works at Berlin’s VeneKlasen Werner gallery, Zheng conducted a tea ceremony prior to the opening last Saturday.

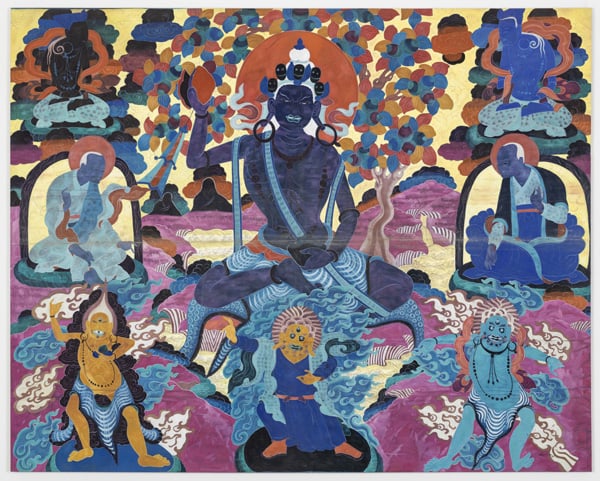

The first two paintings the viewer encounters are reminiscent of scientific charts. The one hanging opposite them shows a Buddhist Thangka. How do they relate to each other?

[The series] The Aesthetic Resonance of Chakra focuses on the point in your body where you should breathe. Take a deep breath as you stand in front of them. Then move the air up. You have to breathe from your center. It prepares your energy for viewing the rest of the show. My whole practice is beyond abstraction or concept. It’s a direct interaction with your body. You don’t have to read or to know anything, but to feel it. You yourself become a part of the artwork. The Thangka is pure energy. You shouldn’t think. It’s not Pop or symbolism, it’s about the subconscious.

But people have different subconsciousness. It strikes me as impossible to anticipate what the viewer will feel standing here. How can you be sure visitors will feel this energy?

You must be under the influence of an education of art history, so you always automatically look for references, you might think maybe this artist invents a new way to make art, but you don’t need to think at all. Just match the vibrations of the piece so only you and the work exist, you are the reflection of the existence of the energy. You can still feel the energy when you go home.

Zheng Guogu The Brain Nerves (Marcel Duchamp)(left) and The Brain Nerves (Joseph Beuys) (both 2014)

Image: courtesy VW (Veneklasen / Werner) Berlin

Art history is also prominent in your work, though. The Brainwaves series (2014) references Duchamp, Warhol, and Beuys. Formally, too, these paintings feel different from the others in the show, though they are all from the same period. What is happening in these?

When you stand in here [takes position] you are right behind Marcel Duchamp’s brain. This lower back part of your brain? Focus on it, and see what you feel. The U shape is what everybody’s brain energy looks like. The right and left sides of your brain, emotional and rational, are sending energy to the lower part in the back for your activity.

This image represents Duchamp’s brain, his consciousness. It’s the final image of his life’s consciousness. The ideal would be a complete O shape, like for Buddha, but his is already at a very high level.

I work with a special medium who sees the magnetic image of the brain, that’s what the date and time stand for. The magnetic brain test only works on deceased people. Otherwise the brain is still too active. Because people usually tend to copy or imitate things they see, your brain might imitate the activity of Duchamp’s brain when you stand in front of it. It might receive a message.

There’s also a painting of your teacher’s brain, is seems like it’s functioning on a very high level. Who was your teacher?

The work connects to the photograph from 1993, hanging in the other room [pictured above].

It was taken in my home town, where I have my studio. I spent one year with him. He has a mental problem, he’s special, he is always in this extremely happy state. His emotional and physical systems are beyond ours, he eats all this rotten food and he doesn’t get sick. We might die if we eat that. I then realized how I should be making art. I realized this man was my teacher, the inspiration he gave me was beyond my entire education, more than Duchamp, Beuys, and Warhol. What he can give me is untouchable, like heat. So therefore I also tested his brain.

What are the intellectual processes depicted in your painting Computer Controlled by Pig’s Brain (2014)? Does this work also relate to brain activity?

My hometown is across from Hong Kong, so we see the lit signs from there. You never see slogans in English characters in China. Nothing mixed, but in Hong Kong, the Cantonese mixes with English in a total hybrid of east and west, which becomes a new thing. But the content of the signs [we see] is really flat, it’s gossip and entertainment. The titular pig is actually me. I don’t know anything about computers and I processed the signs and slogans on a computer before painting them, so I’m in control but I don’t know what I’m doing.

What is different in you solo work compared to your work with the Yangjiang Group?

The group originally intended to bring calligraphy into contemporary art. But for me it’s more expansive than that, the medium is not limited to one type. I do architecture, painting, even video.

Zheng Guogu One Manipulates into two, two integrates into one No.2 (2013)

Image: courtesy VW (Veneklasen / Werner) Berlin

I also get the sense that your solo work is more leaned towards the spiritual world. For example, the Thangka works in this show, or the Mantra wheels.

I bought these Thangkas from the local lama years ago, and painted over them. In Buddhism, there’s this notion that the world is inverse. What we believe and do is the opposite of the teachings. So I bought this Tibetan Thangka and painted on top with the opposite colors. The oil paint covers the natural materials used for color, which are ground stones and granite. These original materials possess such a strong energy that the oil paint can’t really cover them. The energy comes through. So that here, the negative color completes the other side.

Tibetan Buddhism is also called the Religion of Energy. Energy is under the law and principle of things, under their surface, so this work also seemingly hides something. It emphasizes the energy. It will also give you energy. The Thangka is always talking about the rule of the universe, energy.

In Tibetan culture what they refer to is beyond our world, and what we’re doing is earthly. So I want to find the crossover, which is, for me, contemporary art, to combine the two.

Your practice oscillates between being tongue-in-cheek and very sincere. How do humor and sincerity coexist in your oeuvre?

I used to drink a lot and do calligraphy, and the following day I couldn’t remember having drawn them. Then I quit drinking, as doctors warned me they can’t help me if I don’t stop. But I also tried to cure myself. So I found acupuncture, and maybe the world needs to tend to this energy. Maybe 2,500-year-old Tibetan culture once gave wisdom to people, but society is moving away from it. That’s how I came to focus on the topic of energy in my work. Every tradition is a break with something older, and it’s always transforming. What we think is traditional now, used to once be just the most popular fashion, that’s how it became a prevalent tradition. Every tradition actually changes the previous thing. The world is always transforming and isn’t still.

Zheng Guogu, “Visionary Transformation” is on view through April 25, 2015 at VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin