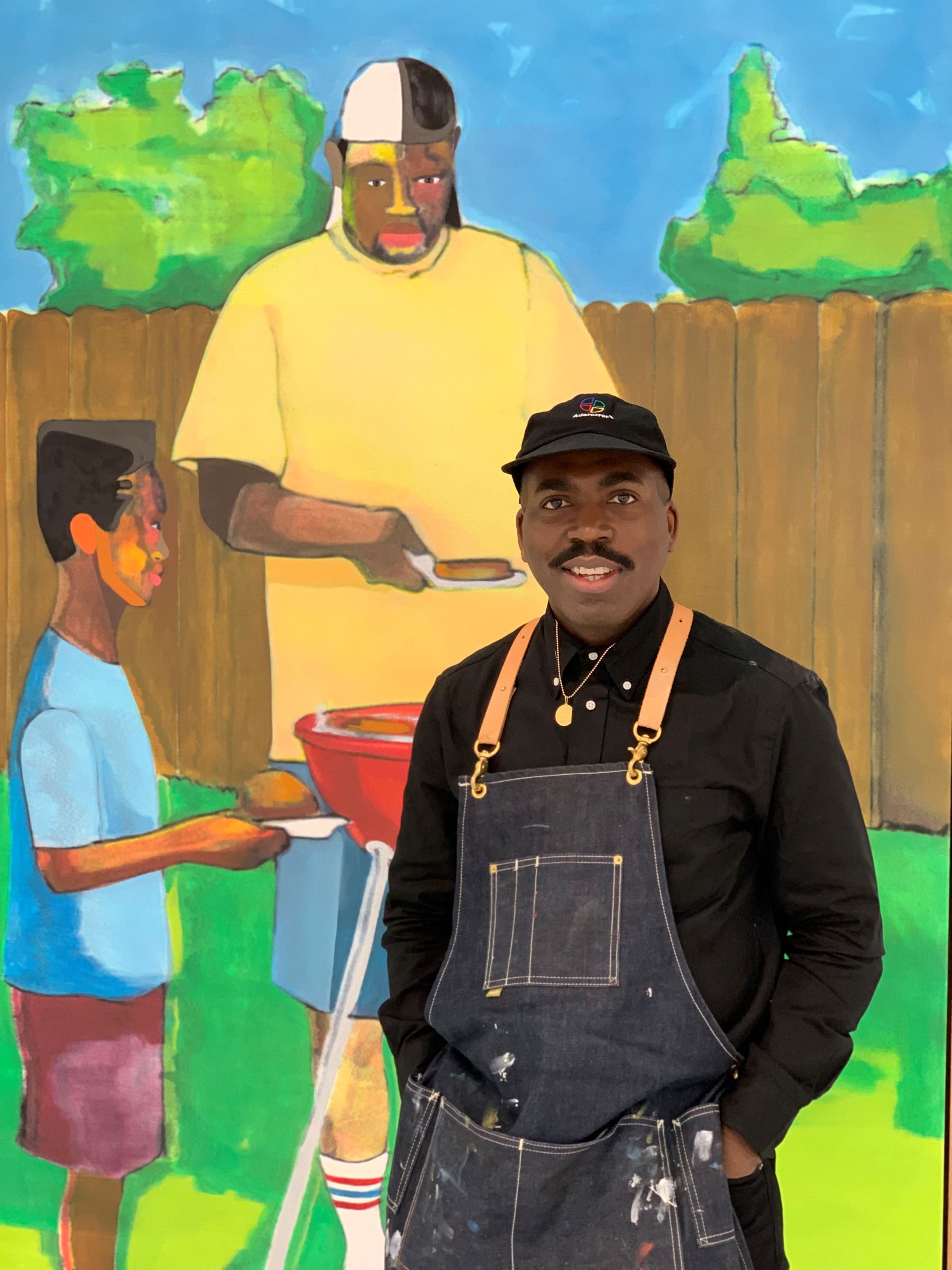

This past November, I had the pleasure of meeting Derrick Adams at his Brooklyn studio. The critically acclaimed, multidisciplinary artist is known for his inventive portraits of black subjects. I’ve been a fan for some time now, and I’m not the only one.

Over the next few months, Adams’s work will be featured in “Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle” at the Peabody Essex Museum, as well as in two separate solo shows: “Derrick Adams: Transformers” is set to open at Luxembourg & Dayan in London on February 10, and “Derrick Adams: Buoyant” comes to the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers on March 7. Salon 94 is also planning a booth organized around the artist’s work for next week’s Frieze Los Angeles. That’s a lot to talk about.

Our conversation ranged from Adams’s creative vision to his advocacy for other artists, his ambitions to open an art residency in his hometown of Baltimore, and his love for What’s Happening!

I see you’ve been revisiting Baltimore often, particularly recently.

I’m from Baltimore, and recently I just became more interested in the creative culture of Baltimore. It’s been prospering for younger artists—primarily artists of African descent.

Because these young artists are not in New York, they are away from the so-called market and able to develop in a way that they might not have been able to do here [in New York]. But they are still very close to New York, so they’re still on the radar.

I grew up in Baltimore and that was not an option when I was in my early twenties. It’s really interesting to see that change.

So I became interested in that growth, and I just started to go into Baltimore more often, just to be a part of it and to find out if I could help to push it along, through my connections or my experience here in New York. Also [I wanted to] redirect some of the people who are interested in what’s happening here [in New York] towards looking at what’s happening in Baltimore, since it’s so close.

Derrick Adams, Woman and Man in Grayscale (2017). Image courtesy Derrick Adams Studio and the Brooklyn Museum.

The first time I met you was at a Swizz Beatz party, over the summer. Smack in the front room of his home is the portrait you did of him and Alicia [Keys]. But you’re not normally doing portraits of celebrities. Who are the people in your portraits?

Usually they’re from imagination or some photo reference. If I photograph someone or source an image, I usually create composites, variations of different types of compositional poses. Normally the faces are imagined.

But I do have some paintings that are directly of family members, such as my “Floater” series, some of which are paintings of my family in the pool.

With Alicia and Swizz, I was asked by the Brooklyn Museum to make a work because they were being honored. Because they are friends and I spend time with them, I decided that it’d be interesting to make a portrait that I felt represented them but that also aestheticized them in a way that made their image fall in line with some of my other work.

The work ended up being a print. But I wanted to give them the original painting, because I thought it would be great for them to have that.

When you’re working, what inspires you? How do you get into the mode of actually putting paint to canvas?

Usually, I’m attracted to things that are in my daily space or in my neighborhood. Things I see when I’m walking around. I pay attention to everything, from store windows, to people in cafes talking, to people on the corner communicating. I like to think about surroundings as source materials.

When I’m around people, I’m constantly looking at the aesthetics of how they wear their hair, how they communicate with each other. I believe that, as black people, there are things we do, things that are common practice, that are also very complex and interesting forms of culture and cultural production.

Derrick Adams, Floater 80 (2018), which is set to be shown in “Derrick Adams: Buoyant” at the Hudson River Museum. Image courtesy the artist.

One thing that I’ve liked in your work is that you have these three themes that you revisit over and over: the black portrait; images of people in the pool; and the television.

When I started the “Floater” series, I was thinking about new ways of representing the black figure in portraiture. Frankly, we all live in a postcolonial environment. As black people, we shouldn’t have to acknowledge it in everything we do.

You can use your black radical imagination to talk about the way you want to live. It’s similar to how rappers express themselves: One of the strengths of rappers is the ability to imagine the most elaborate lifestyle. Eventually, if they’re lucky, what they’re talking about becomes their reality.

I feel the same way about art. If you want to depict yourself being a certain way and living with a certain level of freedom, you actually can promote that through art. You can put that image in the world so that people can look at themselves in the same type of way.

As I say all the time: You can protest or be a part of an activist culture and still spend time with your family, still go to the beach. I think we should celebrate the fact that regardless of all the things happening to us, we’ve still been able to find time for our families, to spend with our friends; to have really in-depth conversations about things that matter to us socially, politically, but still talk about things that we like: music, fashion, etcetera.

The work I try to make is a testament of perseverance. We have to represent a certain sense of normalcy in order to stabilize the culture so that young people who are coming after us can look at themselves as fully dimensional humans—not always pushing against something, but basically just existing in a way that’s unapologetic and natural.

For so long there wasn’t any television programming that depicted African Americans in a good light—or even at all. Is that why you’re revisiting the television over and over?

One of the reasons I started the “Live and In Color” series was remembering the shows that featured a primarily black cast and how those shows have impacted me, and also impacted black culture.

Derrick Adams, King for a Day (2014). Image courtesy Derrick Adams Studio.

Any shows in particular?

The Cosby Show. A Different World. The Jeffersons.

What’s Happening! was my favorite show, with Rerun, Shirley, Raj—it reflected young black kids having fun. More than other shows, it wasn’t focused always or primarily on the economic situation of the people in it.

Those types of shows have empowered me as a person because, at a time when I was growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, we saw films like Gone with the Wind, where black people were depicted as overly exaggerated characters. I felt very disconnected from representations of subservient black figures on TV. Women in our family were more like Weezy Jefferson or the mother on What’s Happening!

If there were shows with black subjects, we watched those shows. The small number of shows that came on with black characters, I watched them on repeat. I would say my life was primarily on the black channel.

I remember telling my grandmother [that] I didn’t feel there was a lack of representation on television shows. I felt like there was a little lack of representation in commercials. The commercials that I watched as a kid that represented kids, in families, really didn’t show us at the breakfast table. I feel like those were way more harmful or excluding than the shows.

As if black kids didn’t eat cornflakes.

My family was very strong and found a sense of representation of themselves in black culture and by being very visible in that community and through community engagement. I never felt in any way not represented. I think that’s the case for most black Americans. I think we start to understand exclusivity or unevenness when we get more into the institutional space, at the Ivy League level. That’s when I think we start to realize the idea of being separated.

It’s like, before you get to Columbia, you probably thought everyone gets to go to Columbia. Then you get there and you’re one of few.

Right. It’s like you’re from another planet, representing your planet. In some cases, we are like the representative, there to speak on behalf of a group. Sometimes that can be a good thing to be. But I think there should be a choice. Some people don’t want that responsibility.

Can you talk about other artists who inspire you today?

Mickalene Thomas is a very big inspiration to me as a peer. We attended undergrad together, so we’re close, but that closeness is really coming from a sense of admiration and respect. There are quite a few artists, like David Hammons and Emma Amos. Adrian Piper. I mean, so many. Ed Clark was an artist whom I really loved. There are also artists whom I learned about in an academic setting, like Bruce Nauman, whom I respect and appreciate, and Nicole Eisenman.

Derrick Adams, Finding Derrick 6 to 8, (2016). Image courtesy Derrick Adams Studio.

It’s interesting you mention Bruce Nauman, very much an interdisciplinary artist like yourself. In 2016, you did the performance at the Met, “Finding Derrick 6 to 8.” When did you first discover you were interested in performance art?

Performance is always part of my vocabulary as an artist. I think of art in terms of asking what’s the best form of execution for the conversation you want to have. Sometimes things are way more effective as a performative experience versus a painting, or as sculpture or photograph.

In that particular piece, I was invited by the Met for a series that involved artists commenting on the work in the museum. I picked Sol LeWitt, another artist I really enjoy. My interpretation of his work is that it is about space, form, containment, and fluidity—things that I think are really significant in engaging with public space. As an artist and as a black person, I thought about the idea of navigating these very rigid forms of containment in space and architecture.

Did you design the suit for the piece?

Yes, I measured the horizontal and vertical lines that made up the [LeWitt] composition, and made a reversible suit that camouflaged me within it. For two hours at the museum, I stood in front of the wall. I moved in from the beginning of the wall drawing to the end in slow motion, moving across for two hours, mimicking the formation of the lines as it related to the costume I was wearing.

It was a way of showing that this artist, Sol, was really focused on very formal aesthetics and not really dealing with social-political concepts. As a black artist, I enjoy that extra level of content that we have, that we bring to the discussion, going beyond just the formal.

I like the idea that we as black people have this little extra something to add to the table of looking and seeing and experiencing, based on where we come from.

There’s an interview you did with Orlando Live where they asked you to describe yourself in one word and you said “facilitator.” From talks I’ve had with other people who know you, they also mentioned you are the facilitator, and very influential in helping young artists. Can you talk more about how you decide which artists to help and why?

That’s always complicated. Usually I’m really open to helping all artists starting out. But its like what Biggie said: “When I get into the door and I leave the door open, it’s up to you…” I’m like, “This is what I can do. This is who I know.” I can bring you here and introduce you to where I work—but after that it’s on you.

And that’s really the difference between who makes it and who doesn’t. The door was open for you—you still have to go in.

I’m just connecting people. Like, there’s a young curator who wants to do a show and I’ll connect them to the institution that I know, or do anything I can to push the conversation along and empower the next generation.

The younger generation has another level of professionalism. I’m from the generation that comes from the ‘60s and ‘70s. For me, it’s always been about just making it work, not really thinking about success in a monetary way, but more about success within your peer group and the way they view you and respect you.

Some of these artists, like Ed Clark and Frank Bowling and Howardena Pindell—these artists continued making work without monetary support. Having support from peers is what kept them going. To me, that’s what I think about when I think about success as an artist. Everything else is extra points.

You’re on the board of a couple of organizations: Project for Empty Space, Eubie Blake in Baltimore, and Participant Inc. on the Lower East Side. Are you also in the process of starting an artist residency of your own?

That’s what I’m doing in Baltimore. I got some property in Baltimore and I’m in the process of renovating it, forming a modest retreat—a space for visual artists, writers, culinary artists, and technology-based individuals.

What would be the duration of the residency?

A month. There are studios that are being built and there are quite a few rooms in the house. So the goal is that in 2021, when it’s all done, we’re going to start inviting people to participate, always including one person from Baltimore. The local person will help direct visitors to real, significant places that will inspire the work.

In cities like Baltimore—or Detroit, Wilmington, and Philly, for that matter—there are communities that are not highlighted. In all those cities the fact that there are still people there, black people who are living in these cities who are keeping these cities afloat with the little bit of income they have—that’s something that people should focus more on versus what’s not happening in the city. Regardless of where the finances of certain cities are, there are people living in these urban spaces who are basically the heartbeat of that place.

This residency will be an artist retreat, where people can come to Baltimore and reflect and learn more about the culture. I really want to link the artists who are in Baltimore, who are on the come up, so they don’t have to leave Baltimore, they don’t have to come to New York to be successful. Maybe I can bring New York down to Baltimore so people in New York won’t think Baltimore is so far.

Wall Street is starting to buy more black artists. How do you feel about that?

I think it’s great. There are quite a few investment bankers who are interested in supporting artists, black artists, and a lot of black financial people who are supporting the arts.

Contrary to what most people believe, there are quite a few black collectors out here who are dedicated to buying. I think that probably half of my collectors are black. From various levels: actors, musicians, doctors, lawyers, financial people.

I think that one of the reasons for this is that my work represents a life that is aspirational and reflects the way that some of these people live. After working all day or being in an environment where you have to deal with so many different types of people, you want to come home and see things that are relatable. I don’t think you want to come home to a noose.

The audience I’m interested in wants to see how they live and see what they aspire to be. That’s what I’m more focused on.

One thing that has been very consistent with anyone that I’ve ever talked to about you is that you’re such a nice person. I’m thinking about Amanda Uribe, who introduced us, Alaina Simone, and Anwarii Musa. How do you remain so humble when you’re pretty much at the pinnacle?

One thing I’m adamant about as an artist is that I don’t want to be the only person celebrated. I’d rather everyone at the table be celebrated. What I love the most is when I’m at an event or a party at someone’s house and I look around and everyone in the room is doing something. It’s all black people doing all these amazing things and I’m like, wow, this is great.

And I say to myself, this is what we should be making work about, this type of atmosphere. Young black people should see that there are very normal, very consistent spaces like these—regardless of what’s happening in the news, regardless of what’s happening on social media. With all the conflicts that we’re having, we’re still finding the time. And not everyone in this room has money! These aren’t people who are all well off!

That’s what I’m thinking about in my studio: What can I reveal that has not been shown? And it always goes back to the simplest of things, like normalcy. Black people—not entertaining, just being, living. Letting people deal with that as reality.

We’re sitting on this pool float. We’re thinking about life. We’re thinking about nothing. We don’t have to think about something every day. It’s a real human experience not to ponder on things constantly.

Derrick Adams, Floater 66 (2018). Image courtesy Derrick Adams Studio.

It’s liberating.

Even when I wasn’t in the position that I am, I always knew that that’s what I wanted. I was making that work. I didn’t know that that work was even radical in the way that I see it as being radical now until I started to have a conversation with people—even black people—who thought that my work was “positive.”

The fact that my work is considered “happy” or “positive” in relation to something else shows that there’s a problem. You can’t just look at this figure as being, just being. You still have to categorize it as a response to something else.

I think about what I want to see when I turn the lights on in my studio. I don’t want to bring the stuff outside of my studio that I think is problematic into my private space. I want to bring the things that I think are precious and valuable into my studio. That’s so important