The search for Cleopatra’s tomb continues yielding new clues. This month, Egyptian authorities announced that ongoing excavations by the Egyptian-Dominican archaeological mission at the sacred city complex of Taposiris Magna have turned up an array of new discoveries, including a temple, a necropolis, and a foundation deposit rife with treasures like coins, pottery, and, potentially, a bust depicting the final Egyptian empress, Cleopatra VII.

The dig was led by Kathleen Martinez, who has been searching for Cleopatra’s long-lost tomb for 20 years now at this very site, just west of Alexandria. Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus founded the bygone city of Taposiris Magna, also known as the “Great Tomb of Osiris,” around 275 B.C.E. Egypt’s last dynasty, the Ptolemaic Kingdom, was established here—and Cleopatra VII, that kingdom’s final ruler. All 14 Ptolemaic leaders’ graves remain at large. While experts widely believe that Cleopatra and her cohorts’ bodies all lie in her sunken palace, Martinez maintains that Cleopatra’s was spirited away through a series of underground tunnels she found in 2022, which lead to Taposiris Magna.

The foundation deposit cache. Photo: Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Thus, excavations at Taposiris Magna continue. Near the southern edge of a wall enclosing the city, Martinez’s team discovered foundation deposits—caches buried long ago to bless the building being constructed. Egyptians built the wall in the 1st century B.C.E., to ensure that caravans passing through paid their toll. The deposit found beneath this structure also included oil lamps, a scarab amulet that reads “The justice of Ra has arisen,” and a trove of 337 coins—many featuring Cleopatra’s silhouette.

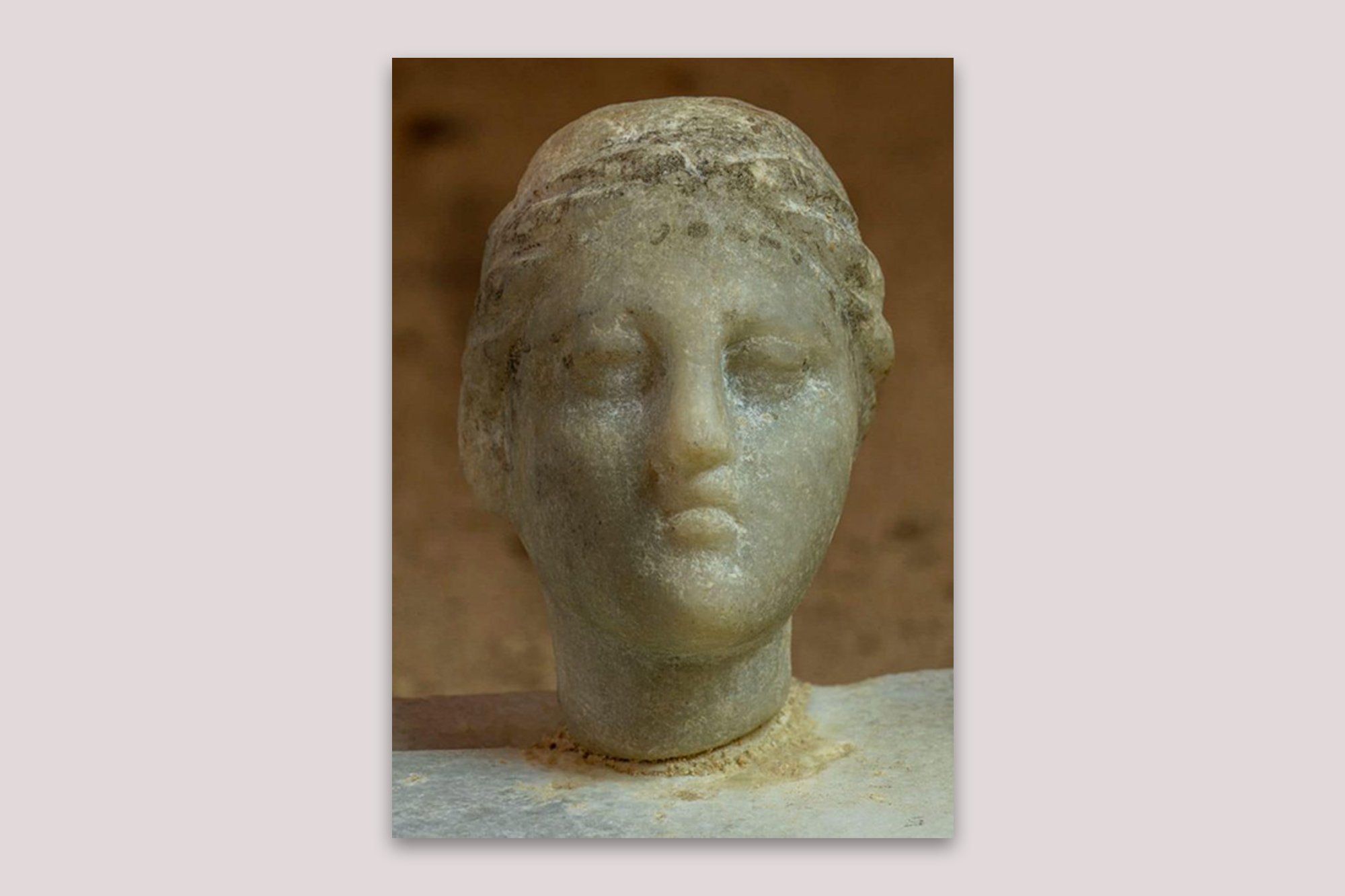

A limestone statue depicting an unknown king wearing the Nemes headress and a bronze statue depicting the fertility goddess Hathor also emerge. Nonetheless, the suspected Cleopatra head bearing the royal diadem has proven by far the most sensational part of the haul. In a release, Egypt’s secretary general of the supreme council of antiquities Mohamed Ismail Khaled remarked that “while Dr. Martinez believes that the marble statuette depicts Queen Cleopatra VII, many archaeologists dispute this claim, noting that the facial features differ from known depictions of Cleopatra VII.” Most think it depicts another royal, or a princess. Zahi Hawass has even taken a look and offered his verdict. “I looked at the bust carefully,” the famed former antiquities minister told Live Science. “It is not Cleopatra at all; it is Roman.”

The Cleopatra VII coins. Photo: Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Near a system of tunnels that runs from Lake Mariout to the Mediterranean Sea, Martinez’s team also found “a Greek temple from the 4th century [B.C.E.], which was destroyed between the 2nd century [B.C.E.] and the early Roman period,” the release noted. Excavations around the city’s ancient lighthouse, meanwhile, unearthed a necropolis encompassing 20 catacombs and three chambers—one of which held artifacts like marble busts. Preliminary underwater excavations into the submerged areas of Taposiris Magna, also “revealed man-made structures, human remains, and vast quantities of pottery.”

So, even if the find doesn’t offer any revelations regarding Cleopatra’s whereabouts, it does offer ample evidence about the importance, and history, of Taposiris Magna.