For years, the Miami-based filmmaker and collector Dennis Scholl had wanted to make a documentary about his favorite artist, Clyfford Still. But he needed an excuse. Five years ago, the Clyfford Still Museum dropped one in his lap.

“I got a call from the museum one day and they said, ‘You’re not going to believe what we found,’” Scholl recalls.

Research staff at the Denver-based museum explained that they had recently discovered a trove of super 8-millimeter film and 34 hours worth of audiotapes made by Still himself. The material provides an unprecedented look into an artist who intentionally withdrew from the public eye—whose own story was as cryptic as the paintings he produced.

The material serves as the backbone of Scholl’s new documentary, “Lifeline: Clyfford Still,” which tells the story of the artist through both his own words and the words of others, including his daughters, art historian David Anfam, critic Jerry Saltz, and artists Mark Bradford and Julian Schnabel. It premieres November 12 at the DOC NYC film festival.

A Shocking Discovery

“The tapes were a complete surprise,” Dean Sobel, the museum’s founding director, tells Artnet News. Sobel explains that the materials—stored in shoeboxes—had never been mentioned during the laborious legal process through which Still’s archive was transferred to the museum from the estate of the artist’s widow.

For him, the discovery helps fill in a major gap in the story of the Still, a notoriously guarded man who virtually left the art world overnight in the early ’60s. “Not that much was known about Still before the museum opened,” he says. “I think a lot of myth had built up in the absence of any archival or scholarly work.”

Still sold fewer than 180 paintings during his life—just enough to support his family—and opted to keep most of what he made for himself. He also refused to allow his work to be reproduced in photographs (even after his death) and rejected a number of opportunities to show—all of which helped push him further into obscurity than his peers.

“From the time he passed in 1980 until the opening of the museum, Still was systematically being written out of the canon,” Scholl says. “If you allow the market to decide who you are, then the market will ignore you if they don’t have access. So the museum—and now, the tapes—give us the opportunity to reevaluate him in the context of those other Ab Ex giants.”

The market, for its part, eventually caught up. The same month the museum opened in 2011, a 1949 Still canvas sold for $61 million at Sotheby’s, which remains a record for the artist today. Since then, his paintings—the few that are in circulation, anyway—have regularly fetched eight figures at auction. Two days after the documentary premieres, another Still painting will hit the block at Sotheby’s evening sale in New York. It’s expected to go for between $12 million and $18 million.

Clyfford Still, PH-455 (1949). Courtesy of the Clyfford Still Museum.

A Lifeline for a Private Artist

The audiotapes, recorded by the artist himself, provide an unprecedented look into who Still was a person. “A lot of the times he’s simply sitting on the porch in Maryland at the end of the day and pontificating,” says Scholl. “Sometimes he’s going back and reading essays from some of the shows he’s had. Other times he’s talking about his colleagues and the level of respect he has or doesn’t have for them. It’s open and it’s honest and it’s raw.”

Some of the musings can verge on the poetic. “When I hang a painting, I would have it say, ‘Here am I,’” Still remarks in one instance. “This is my presence, my feeling, my self…. If one does not like it, he should turn away because I am looking at him.”

They also provide a glimpse into just how much of a hothouse—to borrow a word from Scholl—the art scene of the 1940s and ‘50s New York was. We learn how other artists measured up to Still’s own fastidious standards. He respected Jackson Pollock’s work, though not his lifestyle. He had no time for Barnett Newman. He resented Rothko, whom Still once considered a kindred spirit but later dismissed as a sellout who stopped growing as an artist after he had a family. (When Still learned of Rothko’s suicide in 1970, he allegedly said, “Evil falls to those who live evil lives.”)

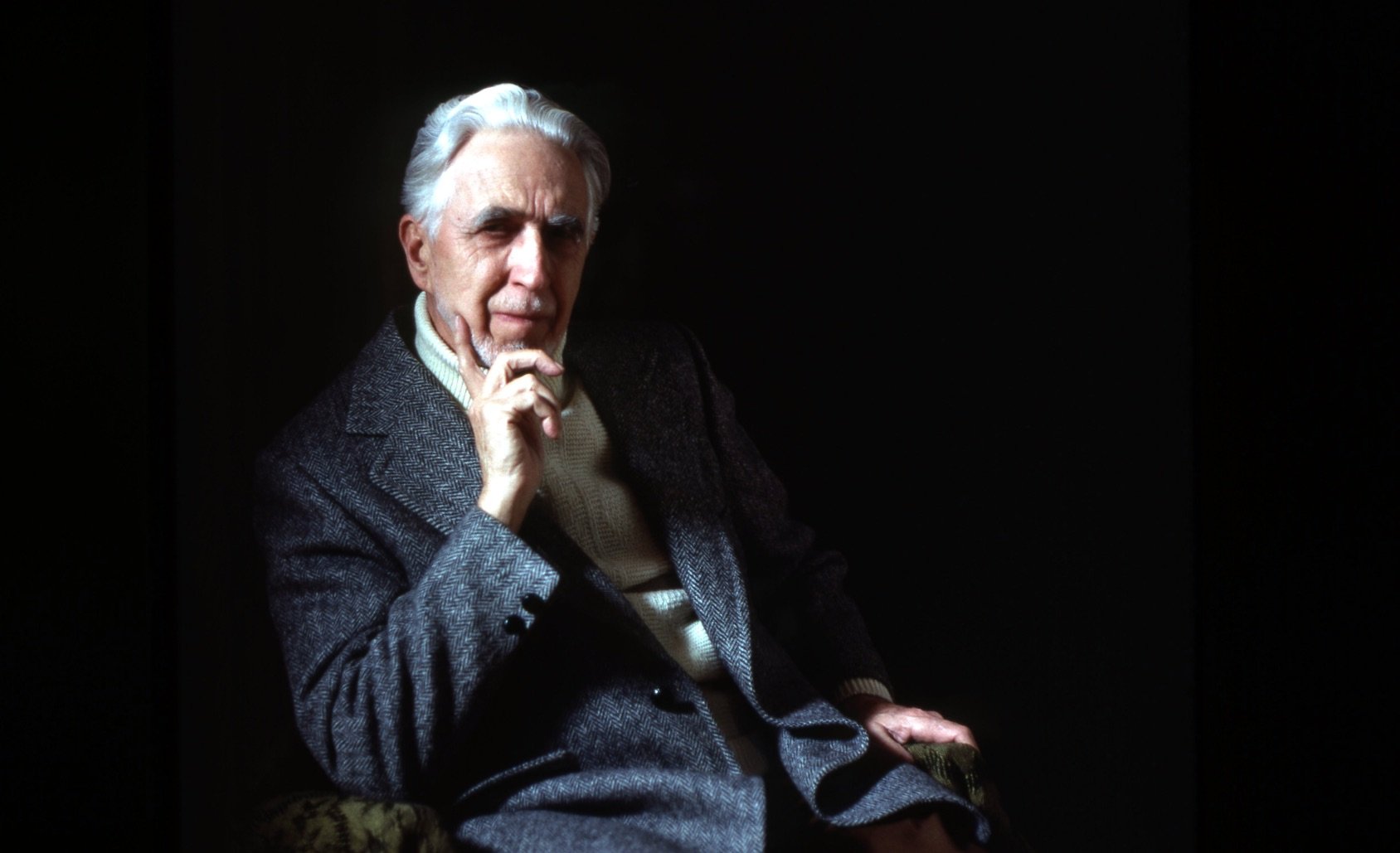

Clyfford Still with his family. Courtesy of the Clyfford Still Museum.

Ultimately, Sobel notes, the tapes shine a light on the biggest questions that have surrounded Still since his death, and even before that: “Why did he brake away from the art world? Why did he want a single monographic institution for his work?”

For Sobel, the tapes show “just how much he cared about what he was doing. He thought the act of painting, and specifically what he was adding to that long and messy history, was critically important. I think all the reasons he did other things connect back to that.”

Indeed, Still was unabashed in his belief that he was the greatest living painter of his time. He didn’t pretend that painting wasn’t the most important thing in his life, even around his family.

“The word that I would use is ‘uncompromising,’” Scholl says. “I think that he was uncompromising in his position as to what it took to be a great artist, and he was uncompromising in his unwillingness to let the machine that was the art world do with him what it would.”

In a particularly poignant moment in the film, Still’s younger daughter Sandra recalls something her dad told her that she never forgot: “He made it very clear—and he bragged about it once—when he said he leaned over my crib and said, ‘I love you, babe, but you don’t come first.’”