Throughout history, the most widely circulated images of black women have been made by photographers seeking to capture something “other”—the exoticism of bare-breasted tribal women, the exceptionalism of dark-skinned performers, the black working woman as synecdoche for the entire black experience. The black female body has been photographed as sculpture, form, and cultural furniture for a white gaze.

Delphine Diallo, a French-Senegalese photographer who lives in Brooklyn, says she’s seen enough of that. Too many images of African and African diasporic women that we see, she feels, have stripped them of their agency and subjectivity.

As a photographer who works almost exclusively with black female subjects, her goal, she says, is to turn that dynamic around—so that every woman she photographs feels that the image she makes of them is a personal gift. Or, as Diallo puts it: “I am not taking pictures, I am giving pictures.”

And through that gift, the artist is creating space for a language of photography that presents black women the way they see themselves. The art world is taking notice: Diallo was one of three artists presented in the inaugural exhibition of London’s new all-female Boogie Wall Gallery in Mayfair, “Notre Dame/Our Lady,” during Frieze Week this October. Fisheye Gallery also presented her three-part collage at the Unseen international photography festival in Amsterdam in September. Her work has also been presented at the Cardiff International Festival of Photography in Wales; at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris; at the Studio Museum of Harlem in New York; and in the “New African Photography” exhibition at Red Hook Labs.

“Photographs so far in history have a very limited interpretation of people of color, so I had this amazing passion and dream to embody a new mythology of women of color,” she said. “Portraiture for me was the key to doing it.”

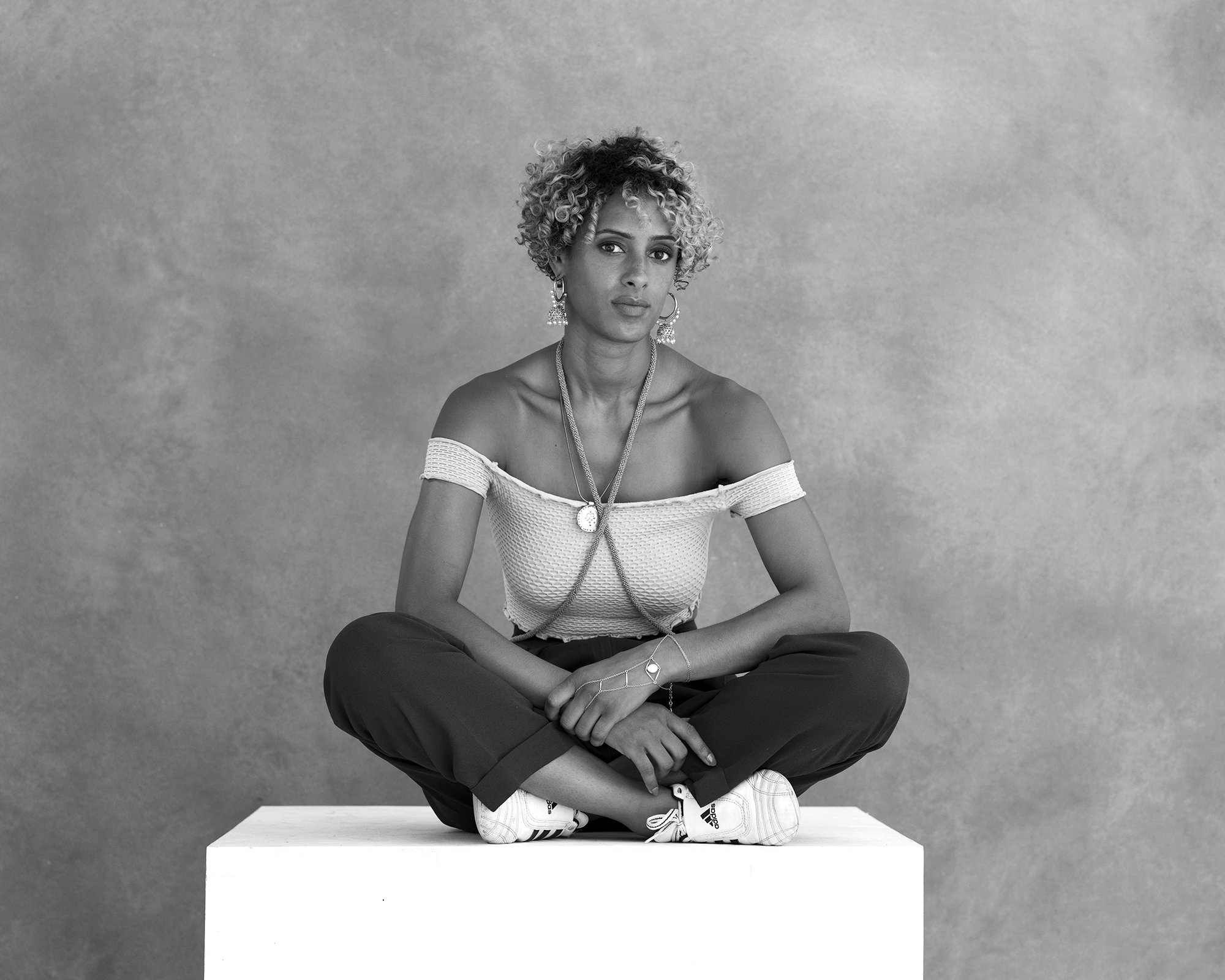

Delphine Diallo’s Jeneil (Yin/Yang) (2019). Copyright the artist.

Coming Up in a Man’s World

Diallo, 42, whose father is Senegalese and mother is French, grew up in Paris and has been living in Brooklyn since 2008, where she currently works as a fine-art and commercial photographer for publications including Essence and Vogue Portugal. She is also a mixed-media collage artist who combines photographic images with magazine clippings, drawings, and other iconography.

“I realized there is not strong history of portraiture of women of color, in photograph as well as in painting, outside of the Orientalist era,” she said in a recent conversation. She was in Paris visiting family, stopping off at her French gallery, Fisheye, and meeting with the historian and documentary filmmaker Pascal Blanchard, who authored the book Sex, Race and Colonization, to help her make intellectual sense of some of these issues.

In her most recent untitled series, Diallo worked with a Brooklyn-based body-paint artist who goes by the name The Virgin Artiste. Her portrait of the artist, called The Divine Connection, shows her outfitted in iridescent blue paint, covered with moons, stars, and clouds. In another image, she is painting multiple eyes onto her own visage.

“The mask is very important to my work,” Diallo explains. “We all wear masks, and the mask can be this persona you can be stuck inside for the rest of your life, until you realize that you can step out of it. The idea is about persona and the idea of transformation.”

Delphine Diallo’s Decolonize the Mind (2017). Copyright the artist.

Diallo tends to collaborate with other black women stylists, craftspeople, and designers to create the look of her portraits. One of her most successful creative partnerships was with Joanne Petit-Frere, a Brooklyn-based sculptor and hair designer who makes what she calls “intricate, avant-garde crowns out of braided hair.”

These figured prominently in Diallo’s series “Highness” from 2011, which explored female power, dignity, and strength using traditional costumes, body paint, and body art that reference female goddesses out of allegory and mythology.

Though Diallo has had success and exposure since she began working full-time as a professional photographer in 2012 (the New York Times has featured her work in its pages, as has Smithsonian Magazine), she still feels that the fine art world isn’t always receptive to her work—or, perhaps, to her, as a woman of color.

During London’s Frieze Week, Diallo said she found herself talking a lot with collectors, curators, and fellow artists about the role of women in the art market. “It feels like there is not a lot of place for woman of color artists,” she said. “In photography overall, only about 13 percent of the artists who are shown are women; when it comes to women of color, it’s going to go under three percent. There are some great things that are happening, especially among the the curators who are women. It’s happening the last two or three years but it’s just beginning. The presence is still very tiny.”

But Diallo feels that she has now hit her stride now with her work, she has found her voice, and she knows her direction. “My intention from the beginning, when I got into photography, was actually to change the gaze,” she said. “I had to have a purpose and my intention has to be completely different. My intention of taking a photograph is to give my subject a real and true reflection of the light that they put in me. I am giving them back something of who they are.”

Le Passage (2019). Courtesy the artist.

The Turning Point

Diallo’s path to fine-art photography was not direct. After graduating from the Académie Charpentier School of Visual Art in Paris in 1999, she went to work in the French music industry as a special effects artist, video editor, and graphic designer. She was successful enough that the work became overwhelming.

“I was working all the time, 15 hours a day,” she recalled. “I was the only woman in the production team, working with mostly male artists, in a very male industry. I always felt that I had to prove to the guys around me that I was worth my salary, and I was not even earning the same salary as them.”

At age 31, she was burned out: “I had a big crisis and I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I felt that everything kind of fell down into a black hole. I had to find a new life.”

By chance, at a dinner party one night, she was seated next to Peter Beard, the American photographer and artist who has lived and worked for decades in Africa. He is best known for his 1965 book, The End of the Game, chronicling the destruction of wildlife due to big game hunting and colonialism in Kenya’s Tsavo lowlands and Uganda parklands in the 1960s and ’70s.

Delphine Diallo’s Shiva (2018). Copyright the artist.

“I discovered his work when I was very young, about 13 years old, and always admired his work,” she said. “When I met him, I was in my early 30s, but I felt something was off, because he asked me if he could photograph me nude. I asked him, ‘Why do you need to photograph me if I am not comfortable with it?’ I told him, ‘Your photography is amazing, but you are missing something about women.’”

Diallo resisted his personal advances, but when she showed him some of the casual photographs she had taken of her family back in Senegal, he was impressed, and invited her to travel with him to Botswana as a creative assistant. He said he would not pay her but he would teach her everything he knew about photography.

“He was totally different then,” she said. “Once he started to respect me, he gave me a shot, and he taught me many skills and he pushed me to do my work. He pushed me to know what was my narrative.” (Beard declined to comment for this story.)

That trip with Beard, said Diallo, was the most critical moment of her career. “I became completely transformed from that trip,” she said. “I decided to break up with my ex and I stopped everything I was doing and decided to start from scratch. I was convinced that this man put me on the right path.”

Delphine Diallo’s The Twilight Zone (2019). Copyright the artist.

Soul-Gazing

After the Botswana trip, she moved to Brooklyn, where she got a job as a waitress to pay the bills and to give herself a chance to develop a portfolio of independent work. Her goal, she said, was to come up with a new language of photography that would present black women the way they see themselves.

She began by shooting portraits of her friends and family members, informing her work with ideas from mythology—particularly female mythology—and anthropology as well as her own intuitive impulses. But her primary objective was to engage with her subjects enough to get to a point where she could make a photograph that didn’t feel like “capturing” an image.

Delphine Diallo’s Black Skin Black Mask (2016). Copyright the artist

“Indigenous people all around the world don’t like westerners to take pictures because they believe that when you take their photograph you are taking a little bit of their soul,” she explained. “So, the entire process is taking without knowing your subject. You are taking instead of giving.”

Diallo, however, was finding herself feeling alienated from American culture, and felt a need to become grounded in ritual and tradition. In 2009, she says she began a personal “spiritual journey,” which has lasted about a decade. “I was looking for a different kind of perception and understanding of the ‘visual world,’” she said.

It began with what she calls a “deep dive into Native American tradition,” because she felt that indigenous people of the United States were more connected to nature and dreams. She traveled to Billings, Montana, where she participated in the 98th annual Crow Powwow, a days-long ritual of dance, song, and drumming that lasts until the participants reach a transcendental state. “At this specific moment, I was aware of my illusion and the fact that my vision will help to heal me,” she said of the experience.

Delphine Diallo’s Samsara (2017). Copyright the artist.

She has returned to the Crow Powwow repeatedly since then, and has also participated in powwows with a New York-based tribe, the Redhawks. Because she had very unique and intimate access to these tribes, she was able to translate her visions through photography, leading to a series of photos she turned into the book, The Great Vision.

And she has taken her respect for indigenous cultures into her studio portrait photography as well. To show reverence for the spiritual being in all of us, she has developed an inclusive, collaborative process. First, she discusses with her subjects how they want to be seen and what kinds of images make them feel comfortable.

“Usually I will spend an hour or two hours talking to them,” she said. “When I think that they are ready to exchange the gift, then we are ready to photograph their soul.”