There’s a heated debate among artists: when creating paintings, should artists use photographs for reference? One school of thought says No, and that to do so creates inferior work, no matter how useful the camera is.

Artists like Steven Assael strongly encourage painting from life, not from photos.

“It just has to be understood that there are dramatic differences between how the camera looks at and experiences the world and how we see it,” he told the Huffington Post. “A camera records a scene in a split second, whereas we see movement over time. We synthesize our observations, and the resulting painting is the culmination of many moments. We selectively choose details and, in that selection process, meaning and surprises happen, giving the artwork a life of its own.”

Al Gury, chairman of the painting department of Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, even went so far as to call the practice “cheating,” telling the Huffington Post that “some use photographs because they’re lazy.”

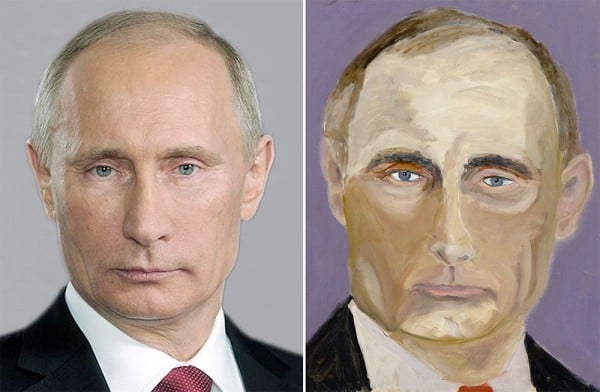

Of course, there is another downside to relying on photographic reference, as Belgian artist Luc Tuymans learned all too well last month when he was convicted of plagiarizing a photographer’s image in one of his works (see Luc Tuymans Convicted of Plagiarism). Even George W. Bush was dinged for the practice (see George W. Bush Used Wikipedia to Copy Portaits of World Leaders).

Not that photography doesn’t have its positives: without it, artists in cold weather climates would be far more restricted in the art they can make. Photos also go a long way toward capturing fleeting lighting or weather conditions, creating useful references for artists. The problem is that the intensity of such light and subtle gradations in color often are lost in photos, which also have some distortion in scale and perspective depending on the curve of the camera lens.

The problem, Brooklyn painter and teacher Dan Thompson told the Post, is that artists “get into trouble when they view a photograph as the truth, rather than as a tool.”