People

How Do You Bring a Historic Museum Into the Future? The Uffizi’s Director Is Trying Everything From Bicycle Paths to TikTok

"We're changing our business model, and we have to do it quickly," Eike Schmidt says.

"We're changing our business model, and we have to do it quickly," Eike Schmidt says.

When museums around the world went dark last March, the team at the Uffizi Galleries in Florence rolled up their sleeves and got to work. Its director, German art historian Eike Schmidt decided that if they could not bring people into their museum, he would bring the museum to the people.

Now, he’s preparing to launch the “Uffizi Diffusi” program later this year to disperse art from its storage to dozens of venues all over Tuscany in a series of thematically arranged presentations. Schmidt and local mayors are even working to establish bicycle routes between the cities to connect venues, like the late Renaissance palace in Montelupo Fiorentino and an opulent former thermal bath in Livorno.

The Uffizi has also been rapidly expanding its online presence. It signed up for Facebook the day after Italy’s lockdown, and it became one of the first museums to fully lean into TikTok last April. More recently, it launched a YouTube cooking show called “Uffizi da Mangiare” (or “Uffizi on the Plate”) that features chefs from the region taking culinary inspiration from works of art.

Artnet News spoke to Schmidt about how he’s bringing a sustainable and digital renaissance to the historic museum.

Ceiling frescos in the Uffizi Museum, Florence, Tuscany, Italy. Photo: Exotica.im/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

How did the idea for Uffizi Diffusi and dispersing works from the collection throughout Tuscany come about?

The idea to have a territorial museum is actually a rather old one. First endeavors in that direction were already made right after the Italian unification in the 1860s and ‘70s, but these remained isolated. It was really during the first lockdown last spring that I was looking at how we could actually change our offer in order to respond to these new times we are in—not just the pandemic but also the ecological crisis.

The idea came up to do a territorial museum project in a more systematic fashion, which means really relocating works of art from the Uffizi throughout Tuscany, especially works that have been in storage for decades and would probably never be exhibited in any other way. These are not at all secondary works. These are oftentimes works of art that in different contexts would be on view, but with the very strong collection that the Uffizi has, often these works do not really have the chance to come out except for special exhibitions, or to replace works of art that are on loan.

Florence was having issues keeping its tourism down to a sustainable level before the pandemic. How does spreading the works out help with some of the crowding issues the city was experiencing?

Our idea is really to de-concentrate. That means opening up the possibility of a new tourism. These works that will be spread throughout Tuscany have an identification value and a social value for the people who live here, so we want to bring the works of art closer to where people actually live.

It is an alternative answer to the problem of what to do with large museum storages. Some museums have opened up walk-in storages to give people an impression of what is there, but the problem with that is that you cannot actually take much away from that experience other than being wowed by how many works there are.

What we are instead trying to do is to create individual narratives that have something to do with the art history of the individual towns of Tuscany, like different chapters of one metaphorical book. In order to read the entire book, you have to go to more than one place. People who live in Tuscany will now go beyond their city walls to see how the works interrelate. People who come just once to Tuscany will be able to see so much more of it now that we are showing these works of art thematically, scattered across the country.

A view of the Michelangelo’s painting Tondo Doni (or Holy Family) at the Uffizi. Photo: Laura Lezza/Getty Images.

How does the de-concentrated model relate to the ecological crisis?

Florence is known for over tourism, which we experienced up until 2019. We had such a density of out-of-town visitors that would all eat and leave their garbage wherever. This is not ecological, just as it is not ecological to jet into a town for a weekend just to see the Uffizi, and maybe go to the opera before leaving again. With these works of art throughout the countryside, another great advantage is that it favors longer stays. We are working with the region of Tuscany and with dozens of mayors to create bicycle routes throughout those cities’s venues. We want to blend cultural tourism with nature tourism and athletic tourism. It is healthier and more fun, and better for the earth.

I can imagine these cities’ venues might not have the same security as Uffizi Galleries. Is that true? How will you mitigate that?

Thanks to new security technologies, which took huge leaps in the past two decades, there is top-notch security available that would have been almost impossible to afford before. We are implementing new lighting technology that is more ecological as well as security systems that are going to be able to guarantee a level of security that we would have been able to only dream of before. We are very optimistic about this.

Conservation, which is another important aspect, will be handled by the Uffizi team. We are looking at climate controls to ensure there is stable temperature and humidity at all the venues and that there are no other risks. In two cases, there are projects—the Villa Medicea L’Ambrogiana in Montelupo Fiorentino and the Terme Del Corallo in Livorno—that need major renovations in the low tens of millions.

Villa medicea, one of the venues planned for the Uffizi Diffusi” project. Photo: BlueRed/REDA&CO/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The news about the Uffizi Diffusi comes in a year marked by a major change in your offerings, both via your new TikTok account and your recently launched cooking show, where Italian chefs make meals inspired by a work of art in your holdings. How do all these efforts intersect?

In the case of Uffizi Diffusi, it is more of a geographical outreach project, but we are also very much looking at areas that need to be re-qualified at the edges of Florence. TikTok is preferred by younger people, and so we adapted our language to it. It is different from our other digital offerings on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. For all of these different channels, we follow a different visual approach and language.

The cooking show aims to tease out different aspects of the works of art closer to the people here. It’s not just about the history of art and cuisine but also about inspiration. Chefs propose recipes and cook along with audiences, so audiences can cook it themselves. This idea came about during lockdown, when people lost access to museums and restaurants. We wanted to anchor the works of art in people’s lives. Our hope is that you cook the recipe at home and speak with your family and friends about the dish and the works of art.

Screenshot from Uffizi Galleries’s TikTok.

Is TikTok helping to balance an aging museum-going population?

It is an investment in the future. We have been stepping up our education programs for kids and youth quite a lot. We continued doing that throughout the lockdown and I think that this differentiates us from many other museums that cut down on those departments, and especially on educational freelancers who were supposed to be giving seminars and tours.

We didn’t have any school groups for the past 13 months, but, amazingly, our digital programming achieved exactly what we hoped for: We had 10 to 15 percent more young visitors up to 25 years of age step into the museum throughout the entire period we were open, between June and November 2020, than before. That is very encouraging. In terms of people 19 to 25, we actually even more than doubled our numbers. And in the age group of children from zero to 18, we reconstructed the same amount of young people who came the museum—but it was young people coming on their own volition and not in school groups. It shows that our approach really worked and it continues to do so after we opened this past February. We have far stronger numbers of young people coming to the museum.

Even with all these outreach programs, visitor numbers on the whole plummeted, of course. Was the pandemic as detrimental to the museum’s finances as one might expect?

It was financially terrible as we made less than 25 percent of what we had earned in 2019. But we did put some money aside in previous years, so it was possible to get through last year. We also received government aid. I would expect, and I very much hope, that in the course of this year the situation will be normalizing slightly, and that from 2022 we will be getting back to business.

That is why we worked so intensively on the Uffizi Diffusi project because we have to be ready once the masses return. We need to be offering them a polycentric offering in order to get tourism moving in a new direction. It would be really a shame if all the problems that mass tourism brought about would return as fast as business returns. We’re changing our business model, but we have to change it quickly in order to be able to give new signals when people travel again.

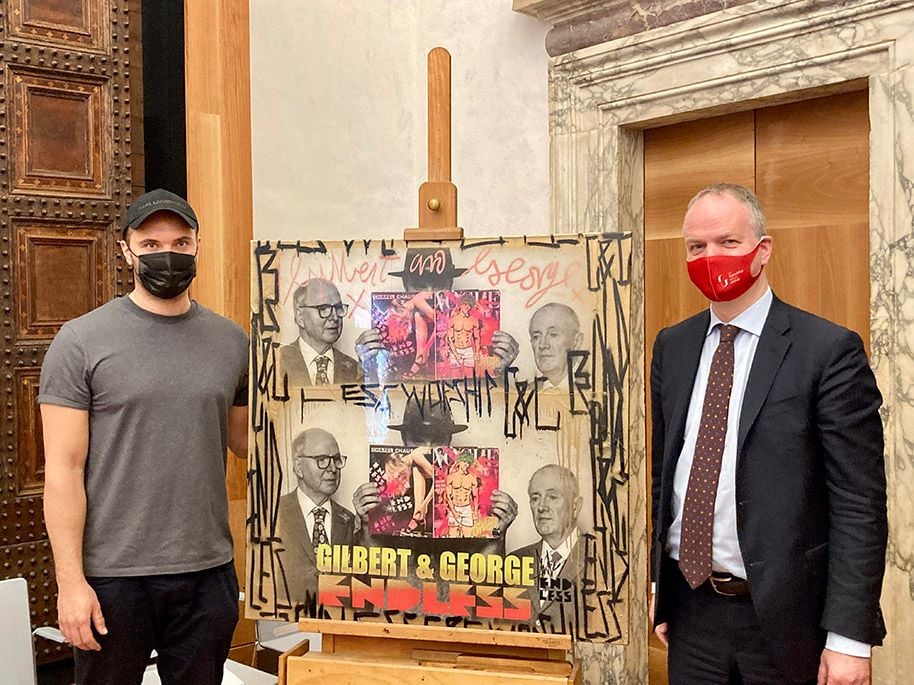

British street artist Endless presents his donation to Uffizi director Eike Schmidt. Photo courtesy of Uffizi Galleries

You made headlines again recently when you accepted a donation from a street artist named Endless. You are not known for having a contemporary art collection.

It doesn’t get focused on much because it was never displayed in its entirety, or even in large parts, yet it is an absolutely fascinating collection, and the world’s oldest and largest collection of self-portrait and portraits. We have works from the 15th and 16th centuries, and the collection itself was started in the 17th century. Since then, acquiring works never stopped. But in the 18th century, it became a particular honor to be allowed to donate a portrait. We have self-portraits by artists as diverse as Yayoi Kusama, Neo Rauch, and Michelangelo Pistoletto.

Endless is particular because he is the first street artist donating a self-portrait. It is a self portrait as a group portrait. We also have a lot self portraits by women painters.

It is a real treasure trove, but oftentimes people are not aware of it. Once we are showing more of the collection, people will also forget about the notion that female artists were a phenomenon of the modern contemporary age. There were lots of them around in the Baroque period and Renaissance period.

Are you accepting donations?

Every time we acquire a work of art, I always get a hundred letters about this. Basically, no, artists are not at all encouraged to send in works of art because we will have to send them back. The tradition is in fact that you are invited to donate a work. Artists then think carefully about what they donate. This is a collection where you will be next to Bernini, Velasquez, and Raphael. They have one shot.