Art World

5 Triumphant National Pavilions at the Venice Biennale, From Finnish Robots to Canadian Floods

See which pavilions in the Giardini made the cut.

See which pavilions in the Giardini made the cut.

If the Venice Biennale is the Olympics of the art world, then the national pavilions are the stadiums where countries unleash the best talent they have to offer. The 57th Venice Biennale held its official preview earlier today, and throngs of people lined up outside the Giardini to get an early glimpse of the much-anticipated national pavilion presentations. (A number of other national pavilions are housed in the nearby Arsenale.)

The wait didn’t disappoint. This Biennale yields a group of strong and diverse presentations. The Instagram-friendly Korean pavilion was an early favorite—all neon signs and wacky interiors, courtesy of Cody Choi and Lee Wan. Other talked-about projects include Anne Imhof’s brooding “Faust” at the German pavilion and Xavier Veilhan’s sound installation and performance “Studio Venezia” at the French pavilion, curated by Christian Marclay and Lionel Bovier.

Overwhelmed by all the options? We’ve zipped around the Giardini and narrowed it down for you. Here are our picks of the five must-see national pavilions at the Giardini this year.

Installation view of Carol Bove’s sculptures at the Swiss Pavilion, 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner New York/London, Maccarone New York/Los Angeles.

1. Swiss Pavilion: Carol Bove and Teresa Hubbard/Alexander Birchler

Located near the entrance of the Giardini, the subtle and elegant exhibition at the Swiss Pavilion is the perfect starting point. Titled “Women of Venice”—a reference to Alberto Giacometti’s famous group of sculptures—the show is an homage to the legendary Swiss sculptor through the lens of three contemporary Swiss-American artists.

In the pavilion’s courtyard, Bove is presenting a group of new sculptures; their placement is beautifully choreographed and inspired by Giacometti’s constellations of figures. Inside, Hubbard and Birchler present a video installation called Flora, which shines a light on the tragic story of Flora Mayo, an American artist who was Giacometti’s lover in Paris in the 1920s.

Philipp Kaiser’s curatorial concept for “Women of Venice” is astute and multilayered, as it also nods to the fact that Giacometti never represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale and thus never showed at the pavilion, which was designed by his brother Bruno in 1952. But Giacometti may have the last laugh. The real “Women of Venice” are on display now at London’s Tate Modern as part of a major retrospective of the artist’s work that opens today.

Installation view of Phyllida Barlow’s “folly” at the British Pavilion, Venice, 2017. Photo Ruth Clark ©British Council. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

2. British Pavilion: Phyllida Barlow

More typical of the biennale in scale and garishness is Phyllida Barlow’s “folly.” A lot has been said about the hotly-anticipated project by the British artist, but no amount of coverage could prepare viewers for the feeling of being dwarfed by these monumental creatures. They seem almost alive; their tumorous growths spill out from the pavilion towards the park.

For the 73-year-old Barlow, “folly” is the culmination of a phenomenal career renaissance. Seven years ago, the artist had no gallery representation and a very low profile; since joining the gallery Hauser & Wirth in 2010, she has ascended to the heights of art super-stardom.

While there is something definitely slapstick about Barlow’s sculptures, which appear on the verge of toppling over, the “folly” evoked here is more dystopian that humorous. A folly is a quintessentially British architectural genre from the 18th century, based on constructions—often in the Gothic or Roman styles—created just for the purpose of decoration. Essentially, this “folly” is a pretense; pretending to be something grander than it really is.

Given the current political climate in the UK, which is in the midst of very tense negotiations over the Brexit process, does Barlow’s “folly” allude to the declining grandeur of her country? Are her precarious sculptures tokens for the now-precarious status of progressive values, like social welfare, borders, and education, that the UK once prided itself in championing?

Installation view of Geoffrey Farmer’s “A way out of the mirror” at the Canada Pavilion for the 57th Venice Biennale 2017. © GeoffreyFarmer, courtesy of the artist. Photo Francesco Barasciutti.

3. Canadian Pavilion: Geoffrey Farmer

Those expecting a sprawling, detailed installation, like the one that propelled Farmer to art-world fame at Documenta 13, are in for a shock. In a neat departure from his signature style, the Canadian artist is literally causing a splash with his Venice presentation. He has routed several water sources—fountains, leaks, drips—into the pavilion. The building, which appears now almost in ruins, is actually undergoing a much-needed $3 million restoration. Farmer decided to face the challenge head-on and incorporate the shifting architecture into his project.

Unsuspecting onlookers erupted into laughter when they spotted a jet of water emerging from the center of the pavilion. But “A way out of the mirror” is actually grounded in tragedy, both in the artist’s family history and the history of his country. Don’t let the whimsical appearance fool you: death, catastrophe, and the passage of time are Farmer’s main subjects.

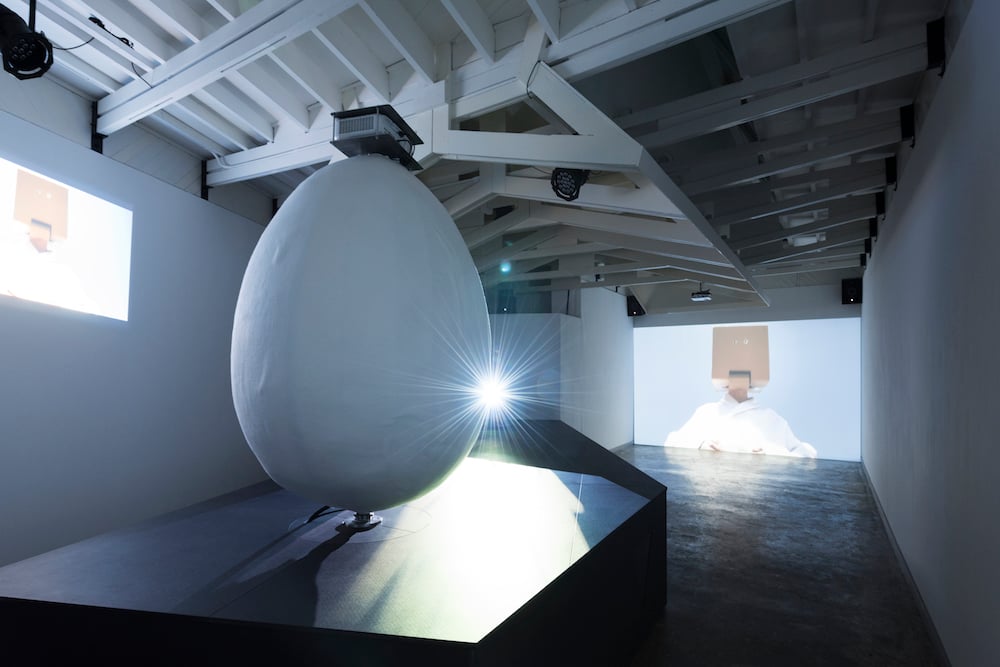

Installation view of Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen’s “The Aalto Natives, 2017” at the 57th Venice Biennale. Courtesy Frame Contemporary Art Finland.

4. Finnish Pavilion: Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen

It seems fitting for national pavilions to tackle the clichés associated with national identities. Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen have done just that in their presentation for the Alvar Aalto-designed Pavilion of Finland.

“The Aalto Natives” is the first collaborative project for the two artists, who share an interest in humor, satire, and caricature, and who followed and admired each other’s work prior to working together.

The result of this art bromance is a video installation that includes a film and two animatronic sculptures. The figures—which move about, talk to each other, and project the film through projectors stuck to their heads—are called Geb and Atum, two superior beings who revisit the Finland they created millions of years earlier and find themselves trying to understand the changes that have taken place.

Hilarious discussions about politics, social media, and ethics ensue. If it sounds bonkers, that’s because it is—in the best possible way. Do not miss it.

Installation view of Geta Brătescu “Apparitions” at the 57th Venice Biennale. Photo © Jens Ziehe.

5. Romanian Pavilion: Geta Brătescu

Last but not least is “Apparitions,” Geta Brătescu’s presentation at the Romanian Pavilion. The show, which feels like a museum-quality mini-retrospective of a pioneer of Romanian Conceptualism, brings together several series from different moments in her long career.

The presentation includes studio-based performances from the 1970s, like Sleep, and the performative sculpture No to Violence! (1974), as well as her Mother Courage series of lithographs from the ’60s and the poignant drawing Mothers from 1997.

Like Barlow’s project, this presentation seems like the cherry on top of an incredible year for Brătescu. Although she has long been a household name in her native country, Brătescu’s international profile is now growing at an exponential rate. Following a widely-praised show currently on view at London’s Camden Arts Centre, Brătescu joined Hauser & Wirth last month. It seems like the art world—and now, Venice—can’t get enough of the 91-year-old artist.