Law & Politics

Phillips Has the Right to Cancel a $5 Million Agreement With Art Dealer Joseph Nahmad Amid Pandemic Upheaval, Judge Rules

The judge said the situation unequivocally qualifies as "force majeure."

The judge said the situation unequivocally qualifies as "force majeure."

by

Eileen Kinsella

Phillips was within its rights to terminate an auction guarantee agreement for a seven-figure Rudolf Stingel painting amid the pandemic, a US District Court judge has ruled.

The decision will likely set an important precedent for the art trade by officially confirming that the global health crisis qualifies as “force majeure,” or an act of God, and therefore can be invoked to nullify certain contracts.

The case has been closely watched at a time when the unpredictable events of 2020 have encouraged auction houses, guarantors, and sellers alike to offset their risk by fighting for more protection in contracts. The outcome may intensify this fight, as sellers could become increasingly nervous that guarantees may not always be iron-clad.

A company affiliated with Joseph Nahmad, the youngest member of the art-dealing Nahmad family dynasty, sued Phillips in July over the deal-gone-wrong. Phillips had agreed to guarantee the Stingel for a price of $5 million—but later notified Nahmad that it was terminating the contract because it had postponed its sale due to lockdown.

JN Contemporary, Nahmad’s company, contended in the suit that Phillips “disingenuously” used the health crisis as a “pretext” to back out because it believed the market for Rudolf Stingel had softened so much it might lose money on the guarantee.

The judge did not buy the dealer’s argument. Instead, she said, the matter was simple. Nahmad signed a contract stating that “in the event that the auction is postponed for

circumstances beyond our or your reasonable control,” Phillips could terminate the deal immediately and it would no longer be liable to pay the guaranteed sum.

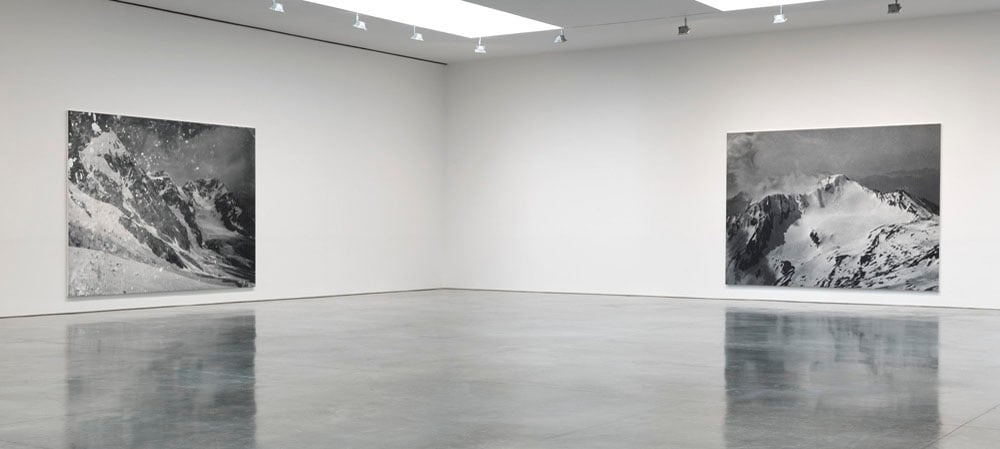

Installation view of Rudolf Stingel at Gagosian in 2014. Photo: Rob McKeever.

The ripple effects from the pandemic, the judge said, clearly qualify as “circumstances beyond our or your reasonable control.”

Phillips declined to comment on the ruling. Richard Golub, Nahmad’s attorney, suggested his client would appeal. “We won’t see them on Park Avenue,” he told Artnet News. “We’ll see them in the second circuit.”

Phillips filed a motion to dismiss the case in early October. In her 36-page ruling, Judge Denise Cote threw out virtually every aspect of JN Contemporary’s argument.

“Phillips kept its promise and followed the letter of the agreement,” the auction house’s attorney Luke Nikas told Artnet News. “The court recognized that and rejected the plaintiffs speculations and legal arguments.”

“Force majeure sounds like a straightforward legal concept, but it is often misunderstood (and mispronounced) by even sophisticated parties,” said attorney Thomas Danziger, who specializes in art law and was not involved in this case. He added that this case in particular is important for a number of reasons, including the fact that it is the first time a Federal District Court sitting in New York has ruled that the pandemic qualifies as a force majeure event permitting an auction house to terminate its consignment agreement with a consignor.

Danziger added: “One thing is certain: even after the vaccine is widely available, the art world will see more Covid-related cases like this one going forward.”