People

Killer Mike, the High Museum’s Newest Board Member, on How He Wants to Make Art More Accessible to the Working Class

The rapper and activist is the latest hip-hop artist to cross over into the art world.

The rapper and activist is the latest hip-hop artist to cross over into the art world.

Killer Mike is a busy man these days. The 43-year-old rapper is a committed activist and father of four. And now, he is also the newest member appointed to the board of Atlanta’s High Museum of Art.

The MC, whose given name is Michael Render, made his mark in the music business with hard-hitting rhymes about income inequality, police brutality, and systemic racism—topics that also permeate his political commentary and activism. His work around those issues has made him a sought-after contributor on the news and a guest lecturer at some of America’s top colleges and universities.

While Killer Mike isn’t a newcomer to the visual arts (he turned down several fine art scholarships to pursue a career in music), his appointment to the board of a major national museum is uncharted territory for the Atlanta native. But he’s not backing down from the challenge.

In a conversation with artnet News, the rapper outlined his goals to increase African American and working-class attendance at the High. He also touched on the importance of arts education, the role of public schools, and the convergence of the art world and hip hop in recent years.

The High Museum of Art in Atlanta.

Photo: Jonathan Hillyer.

How did you first encounter art, and how did it shape your understanding of the world around you and your music?

I’ve been doodling and sketching since before the third grade, and I’ve been a lover of visual arts as long as I can remember.

When I got to high school is really when it became more formal. They had a talent system, where the school would encourage you to tell the teachers and administrators about your interests and talents so they could pair them with your academic work.

I was smart enough to be in accelerated academic courses, but I had a problem because I liked to fight, so they were trying to figure out what other stuff I liked and got me into art and music. I was put into the arts talent system that was run by the former opera singer Nancy Bishop, who traveled the world because of her voice. She had two missions in life: to make sure that children who were into music and art got scholarships to college because of their talent, and to make sure they stayed out of trouble while in high school.

How did you take to the program?

Originally I was in the music program, but when my voice changed I got scared of being in the chorus and singing, I didn’t like it anymore, and I told her I wanted out of the program. So she said, “I read that you like art, so that’s what you’re going to do.” I started doing two art courses a day and my teachers just fostered a love of art—and my love of fine art.

They taught me that whether you get paid for it or not, you have to express yourself. So, from the eighth to the 12th grade, that’s what I did. Then I graduated high school and I told my teachers that I didn’t want to do visual art anymore, in spite of the fact that I had a couple of art scholarships.

I wanted to do music, and I ended up taking an academic scholarship at Morehouse. I went there, but I wanted to do music so bad that I dropped out to pursue my career. Once I got into music I was able to foster my love of art by actually buying art. So I’ve been an art lover all my life, and I’ve been an art collector since I started making enough money to buy it.

Your music and public persona are closely linked to social activism. Does this also influence your taste in art?

I’m a big fan of Gordon Parks, the photographer. I was struck by his photography of the civil rights movement. So even though it’s not all-encompassing to me, I am attracted to that type of art. But everything doesn’t need to be that. Some stuff is just absolutely beautiful and doesn’t have to have a social context at all, I just love it.

When I look at a Jackson Pollock painting, I don’t really think about the social context, there’s just something about the movement of the paint, how big the canvasses were—I get drawn into that.

Visitors in front of a work by Anish Kapoor. Photo courtesy of the High Museum of Art.

You were just appointed to the board of the High Museum in Atlanta. What will you bring to the museum?

I’m a product of the High Museum. I’m a product of Atlanta. I’m a product of the Atlanta public school system. The Atlanta public school system and the High, in my day, were partnered; we took field trips there, and to the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and the Center for Puppetry Arts. The arts movement in Atlanta used to be more closely aligned with the working-class and middle-class kids in public schools, so I would like to reactivate that.

Another thing is that there’s a huge entertainment community in Atlanta. I’d like to engage the music community and the commercial art community and get them in the same room as the museum community and the fine art community. I’d like to be the person who makes sure that some of the money that’s being spent in the music industry makes its way back into the fine arts, so the kids from social conditions that we come from can also be encouraged to participate.

As far as African American participation, I’d like to see it grow. Atlanta is a 50 percent African American city, and I think that should be reflected in the attendance figures of museum-goers. I’m excited about that, and I’m excited about new ideas and things coming up as I meet with the board.

What are some of the ideas and initiatives that you hope to introduce to the museum?

I would like to see more artists that were once labeled street artists in the museum. If you look at Banksy, he’s one of the most famous artists in the world. At one point in time, he was just considered a street artist or a graffiti artist, but he’s ascended to another plateau. There are amazing artists that started in the street.

Over the course of the last year, I bought three pieces from Cedric Smith. He’s based in Savannah, but he’s originally from Atlanta and was originally a graffiti artist. He makes beautiful works that would be considered fine art, using photography and paint. It’s absolutely stunning, his work is in museums, private collections, galleries, and also in the Atlanta airport. Cedric is someone I’d like to see hang in the High. Sever, who is one of the most respected graffiti artists in the world, is from Atlanta. So I would like to see street artists that are doing incredible work, that are museum-worthy, hanging in the High.

You’re regarded as an advocate for marginalized communities. What do you think museums, and the art world more broadly, can do to engage these communities?

I think we should do exactly what worked for me. I got exposed to the arts because of public schools. We are doing a traitorous job of cultivating our children’s minds, values, and spirits. School used to be a place where you went, you learned lessons, you learned ABCs and 1-2-3s. But schools also used to make sure that children knew and appreciated art because art fosters the imagination, and the imagination will breed Einsteins, not just math teachers. If the imagination is not fostered, that does not happen.

From the standpoint of marginalized communities, I think that art gave me the opportunity to see that no matter how working class, poor, or middle class we were, that the bourgeoisie was not better than us and the affluent were not better than us. Because when it came down to artistic skill, it was only about what you could put on paper and how well you could draw or sketch.

Going to art class and learning about art history, and learning that some of the most famous artists in the world came from the same types of background as me, let me know that the people who were producing the art were more like me than the bourgeois and affluent people who were buying the art. Without a working class, without the poor, without middle-class people, you can never produce the type of people who create the art. So the goal of advancing members of marginalized communities should always be to expose them [to the arts] because it grows a child’s imagination.

What can members of these communities do to get their children access to art?

I would encourage working-class and poor parents to take your child to the museum. Usually, it’s cheap or free, depending on where you are. It’s one of the best days out that you can have. For fathers, in particular—fathers who may not have the money to take their children on bigger trips.

I used to take my daughters to the museum and they’re now both lovers of art. Take your child to the museum, have a picnic, talk about what you’ve seen, and enjoy it, because it’s there for us too, it doesn’t just belong to rich people.

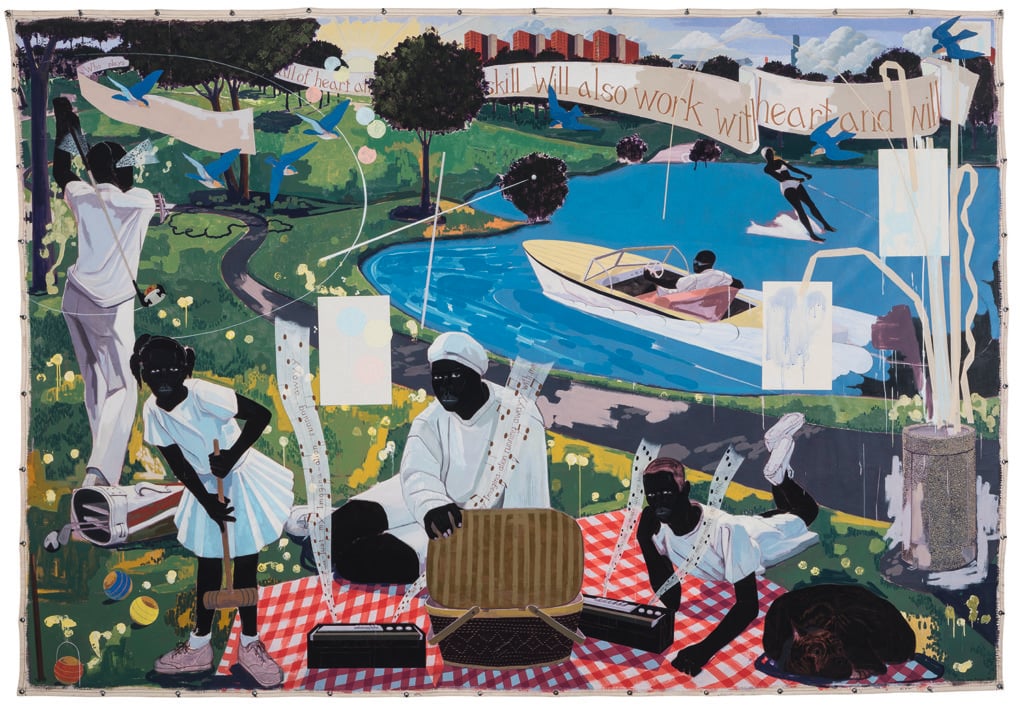

Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times (1997). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

There’s been significant crossover between hip hop and the visual arts in recent years. Swizz Beatz has emerged as a major collector. P. Diddy was in the news for buying a Kerry James Marshall painting for $21 million, and Jay Z and Beyoncé shot their “Apeshit” video in the Louvre. What do you attribute this to?

It’s all art. Artists move between social circles with more ease than anyone. If you look at old pictures of Basquiat and Warhol, they would go party at Studio 54 and the next morning they’d be in a museum or a gallery talking to the affluent about buying their work.

Artists have always had that ability to move among social circles. I think that we’re the glue and connectivity in society a lot of the time. I don’t care who you are—when it comes to a great record or a powerful piece of art, you are emotionally affected.

I think the art world has become more exclusive, so it takes a lot more money to engage in a certain way. But there are living artists right now you can engage with. You might not be able to pay $21 million for a piece, but you can definitely pay $2,000, even $200. Living with art, besides making you feel good and besides being beautiful, depending on the artists you buy, can also be a worthy investment.

You mentioned that you collect art. Who are some of the artists in your collection?

Yeah. I don’t have $21 million paintings, but I do own three Cedric Smiths, two Banksys, I own one Dave White, and I own a few more pieces that I’m forgetting right now because I smoked a joint a little earlier.