This was the first portrait from the life that Bacon attempted; that’s to say, the first to enter the oeuvre. It was done at the Royal College of Art where, for a year or so, Rodrigo Moynihan gave Bacon the use of a studio. [Lucian] Freud expected to have to be there, to make his presence felt as Harry Diamond had done for him. “He asked me to sit and when I came the first time this painting was already virtually finished.” Bacon never normally worked with someone else in the room. He talked, mainly to himself—“exasperation, explanations, self-criticism, unselfconscious”—and there was “a lot of movement and noise and lots of mixing color on the forearms, very, very, strenuous. And a lot of irritation, but not for me though: he’d got such good manners, making it clear that him and it, not you, were the problem. He had a photograph of Kafka leaning on the doorway and he had been using that. I was amazed; it looked terribly good to me. First time he just did the foot. Then I came and stood about four or five times and it got worse and worse every time and then, at the end, not very good. It isn’t very good, but it’s lively.”

The Bacon Portrait of Lucian Freud (1952), in the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, bears no resemblance to Freud and little to Kafka. A coltish young man enters through what could be a revolving door into blinding glare. Soon after this Freud rejected an approach from a Slade student, Lorenza Mazzetti, for him to play the lead in her film adaptation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. It would have been, he thought, an impersonation too far. Another Slade student, Michael Andrews, took on the role.

Michael Hamburger, who had known and quite liked Freud longer than most, liked him least, he said, when he saw him in Soho with Bacon. “He adopted a sort of manner, which I disliked: being very sophisticated and smart and making remarks supposed to be shocking.” Bacon, a practiced exerciser of charm, urged him to think about how he presented himself. “I thought the best thing was to be rude. I don’t mind being on no terms or bad terms. I just don’t want to be on false terms,” was Freud’s response. But Bacon insisted that good manners were useful. “Francis opened my eyes in some ways. His work impressed me, but his personality affected me.”

During the war, when he was summoned to a tribunal to assess his fitness for military service, Bacon had hired a dog from Harrods and spent the night with it knowing that this was a good way to bring on an asthma attack. “He had got this idea about Harrods: if he was near Harrods he couldn’t go too wrong, he thought.” The store was his universal provider. “Everything was linked to Harrods. At first, early on, the bills came and they got more and more nasty but he took no notice and eventually they just pretended that they had been paid. He had a little man there who made these round-cornered suits for him that suited nobody but him.” And he used to filch from the Food Hall, initially out of necessity, then out of habit. It was, Freud thought, simply a case of him helping himself rather than exercising sleight of hand.

“Francis made a great thing about the sensuality of treachery (which wasn’t original) and he used to go on about the cult of the hands, which, in his pictures, he tended to miss.”

Bacon turned to advantage his lack of conventional expertise. To adapt William Empson’s phrase, he learned a style from a despair. Or, in John Berger’s equally arresting phrase, “horror with connivance.” It obliged him to be summary, to skirt formal difficulties,exaggerating to disguise incapability, swiping in the hopes of hitting it off, passing off anguish as hilarity and, occasionally, hilarity as angst. He said, “We live our life through our whole nervous system”; he thrilled to violence, or to the image of violence. Orwell’s image, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, of the fascist state “stamping forever on the human face” is verbal Bacon. The paintings were as showy as figures of speech, as impressive as the ludicrous warning from Mrs. Joe in Great Expectations when Joe and Young Pip hurry off to watch convicts being recaptured: “If you bring the boy back with his head blown to bits by a musket, don’t look to me to put it together again.”

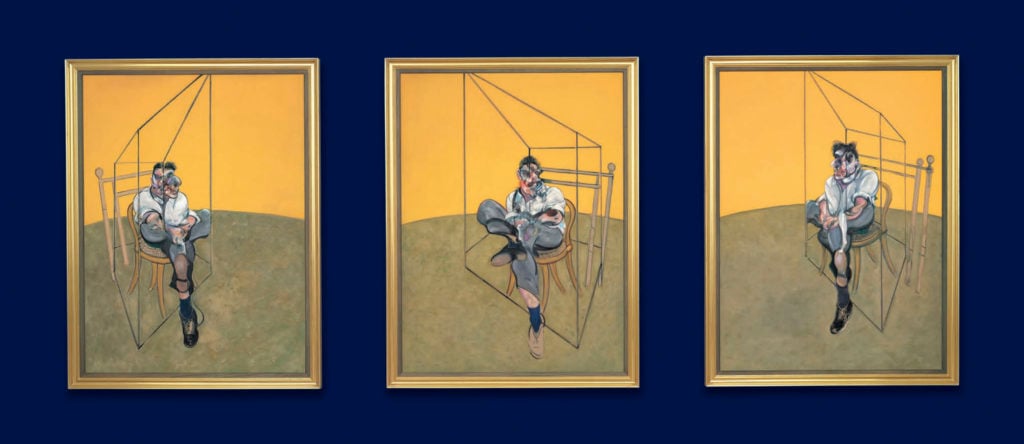

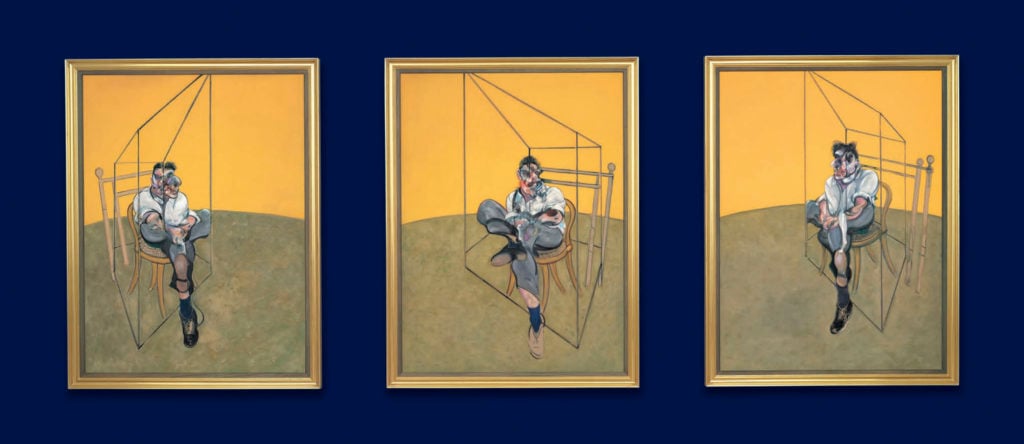

Francis Bacon, Three Studies of Lucian Freud (in 3 parts) (1969). Photo courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

Where, intuitively, Picasso used to slice profiles and reposition eyes, Bacon, relying on reflex, made faces that loomed blurrily: ghostly monoprints lifted from the sticky tonalities of photo culture. Like André Gide not knowing “whether I feel what I believe myself to be feeling,” Bacon found expression in having a stab at things. “Art is a method of opening up areas of feeling rather than merely an illustration of an object,” he told a reporter from Time magazine in 1952. “Real imagination is technical imagination. It is in the ways you think up to bring an event to life again.” Matthew Smith, he stressed, in the introduction he contributed to the catalogue of Smith’s Tate retrospective in 1953, had this essentially painterly imagination. “He seems to me to be one of the very few English painters since Constable and Turner to be concerned with painting—that is, with attempting to make idea and technique inseparable.” What was true of Smith was even more true of himself: “I think that painting today is pure intuition and luck and taking advantage of what happens when you splash the stuff down.”

Suspicious of such notions as happy accident, Freud balked at this. “I don’t know with Matthew Smith. It’s impossible not to like it, but you don’t feel that truth plays much part in it.” Listening though to Bacon, seeing him most days, he found himself echoing his words. “I used a phrase, ‘memory-trace,’ to Colin Anderson. He said, ‘You’re talking like Francis: is that right?’ Sort of bitchy.”

Bacon, Freud found, was better to talk to than anyone else he knew, deft and provocative, always stimulating. And he even agreed to be painted. “It took two or three months. He grumbled but sat well and consistently.” Bernard Walsh, who ran Wheeler’s in Old Compton Street, their favorite eating place, used to go on at them to do portraits of one another. “What I want is a Bacon of Freud and a Freud of Bacon,” he said, so it was a virtual commission. Freud saw it as a favor rendered. “That little picture I really did for him; but when I left Kitty and married Caroline he was so unpleasant. ‘I didn’t know Lucian was a ponce,’ he said, and I was so depressed I fell off the bar stool on to the floor. I couldn’t do anything else as he owned the place and was thirty years older.” Otherwise, he said, he would have thumped him.

Lucien Freud, Reflection (Self-Portrait), 1985. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Francis Bacon, One of Two Studies for a Self-Portrait (1970). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

As with most of the other small portraits he did around that time Freud used a copper plate, small enough to be hand-held if the detailing demanded it. “Life-size looks mean,” Bacon said, whereas shaving-mirror-scale looks intimate. Freud’s Bacon is side-lit, half dour, half sunny, his voluptuous features, nostrils and chin, temples and jowls, uneasily patted together. Sitting knee to knee, within three feet of him, Freud caught the air of unconcern, or diffidence even, the heavy-lidded eyes downcast, blond hair mussed over traces of penciling, a flicker of disdain crossing his mind possibly.

Freud was prompted—shamed even—by Bacon. “I got very impatient with the way I was working. It was limiting and a limited vehicle for me and I also felt that my drawing and my making artifacts—graphic artifacts—stopped me from freeing myself and I think my admiration for Francis came into this. I realized that by working in the way I did I couldn’t really evolve. The change wasn’t perhaps more than one of focus but it did make it possible for me to approach the whole thing in another way.” He appreciated that expression—as distinct from Expressionism, which was pseudo-primitive Mannerism—involved a degree of emphasis bordering on abandon. Bonnard said, “Draw your pleasure—paint your pleasure—express your pleasure strongly.” As Delacroix wrote in his diary, “One never paints violently enough.”

Excerpted from The Lives of Lucian Freud by William Feaver. Copyright © 2019 by William Feaver. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.