Crime

A $1 Million Marsden Hartley That Was Stolen 30 Years Ago and Replaced With a Forgery Is Finally Returning to Its Original Owner

The case took some wild twists and turns on its year-long journey through the courts.

The case took some wild twists and turns on its year-long journey through the courts.

A wild legal case involving a stolen—and then forged—Marsden Hartley picture has finally made its way out of the courts, and now the painting will return to the Chicago company from which it was taken three decades ago.

The painting, titled Maine Flowers (1936–37), was swiped from the headquarters of the pharmaceutical company Abbott Labs and replaced with a forged copy, allegedly by an unscrupulous art restorer.

The real painting changed hands at least twice since then, and several of the key players in the story have died. Now, a judge in New York has ruled against the family of the most recent owner, which sought to retain ownership and insisted that it was acquired in good faith.

“We are disappointed by the court’s ruling, which has the effect of endorsing gross negligence by a corporation over its art collection, at the cost of punishing good-faith current owners,” William Charron, the lawyer representing the family, told Arnet News.

Judd Grossman and Lindsay Hogan, the attorneys who represented Abbott, declined to comment.

The ruling was handed down on December 9 in the Southern District of New York by Judge Lorna Schofield, who wrote that Abbott Labs “demonstrated it has superior title” to the work.

The decision came after a three-day bench trial—in which a judge, rather than a jury, hears the case and rules—that was conducted by videoconference last month.

The case took unexpected twists over the past few years after an insurance appraiser raised doubts about the authenticity of the painting in Abbott Labs’ collection. The fact that the replacement forgery went undetected for so long—roughly 29 years—was a key legal factor.

The most recent owner, New York collector Carol Feinberg, purchased it from Berry-Hill Galleries in 1993 for a reported sum of $351,000. The current fair-market value of the work is roughly $1 million, according to one American art expert.

Dealers at Berry-Hill Galleries purchased it from another source, who bought it from an art restorer named Robert Bruce Duncan, who allegedly stole the picture from Abbott Labs.

In 2002 and 2003, the Feinbergs lent the work to Hartley exhibitions at the Wadsworth Atheneum and Berry-Hill Galleries, suggesting they were unaware of provenance issues. It was those high-profile exhibitions that eventually helped Abbott Labs track down the artwork.

When Feinberg first learned of the issue, she and Abbott Labs attempted to settle the case amicably, even keeping the identity of the painting secret. But at some point, the gloves came off. Amid settlement talks, Feinberg went to a Chicago court in search of declaratory judgment ruling that she was the rightful owner of the painting. She also sought at least $100,000 in damages for “slander of title,” according to a January 2019 report in the Art Newspaper.

Abbott Labs then filed its own suit against Feinberg in New York in 2018, seeking the return of the work. Feinberg’s case was ultimately transferred to New York, effectively uniting the dueling claims.

Only Feinberg’s lawyers dispute that Duncan, the restorer hired by Abbott Labs in 1987, stole the picture and replaced it with a forgery. Her defense team further delved into art history to argue that Abbott Labs never had legal title to the work.

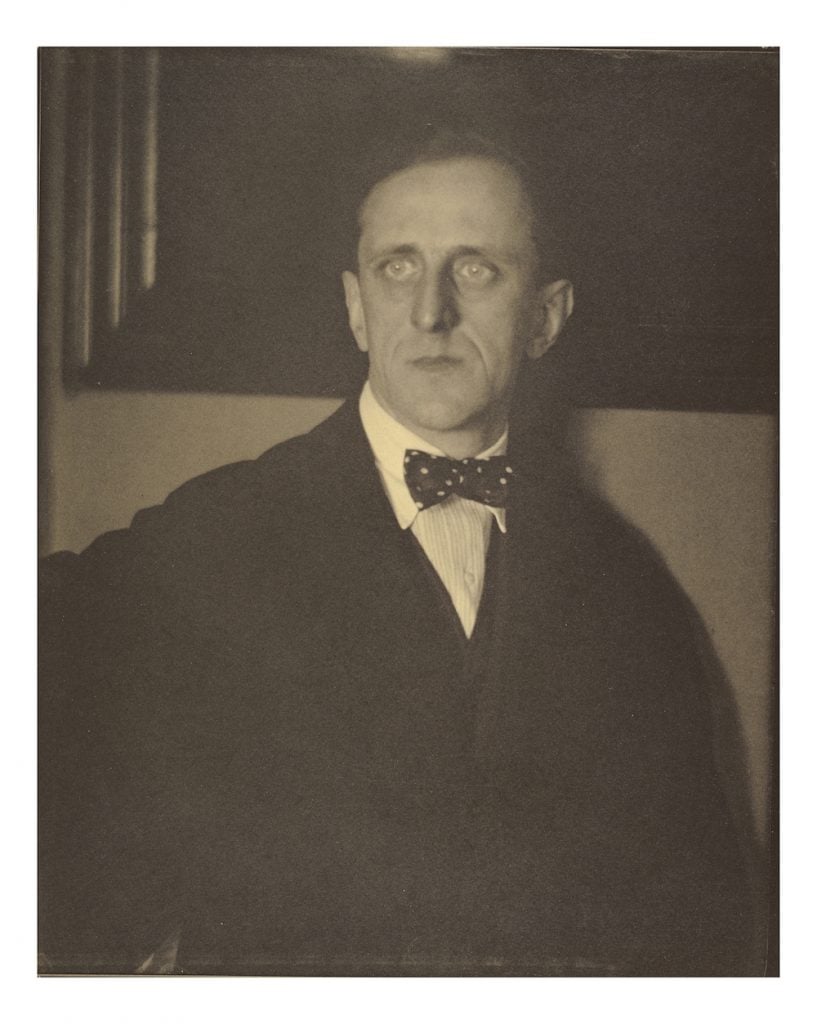

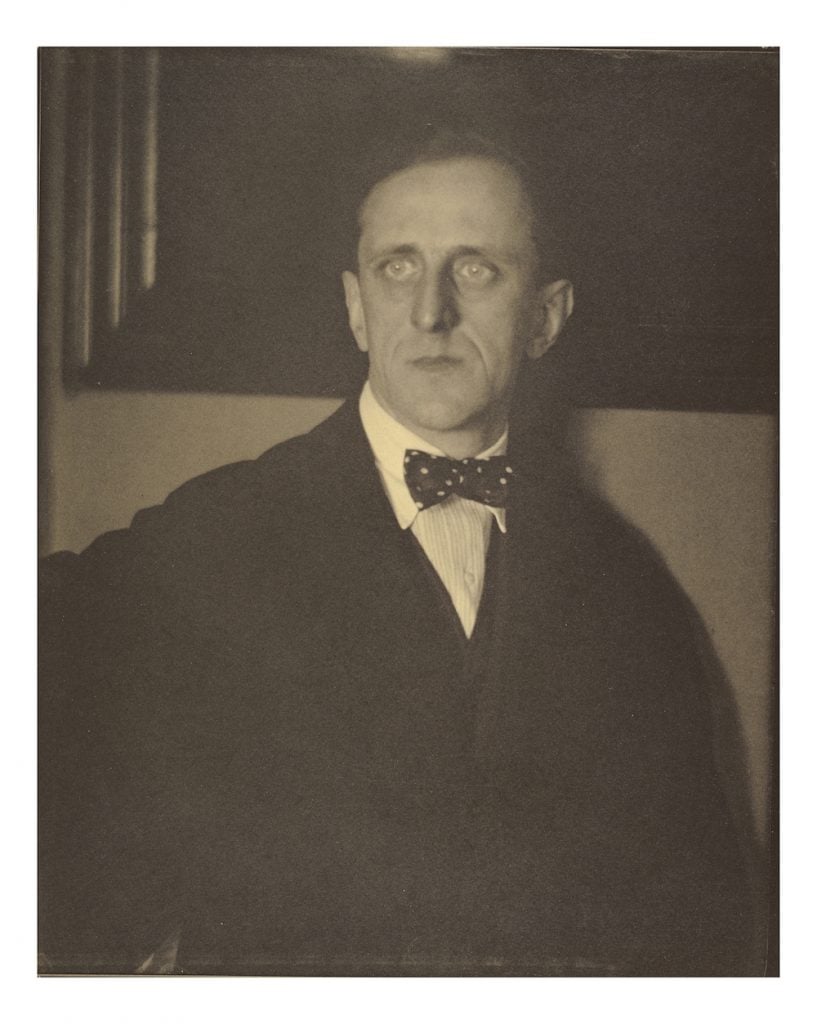

Feinberg’s claims went into the weeds about famed modern art dealer Alfred Stieglitz, who was Hartley’s representative in the 1930s and ’40s, raising questions about whether Stieglitz had title to the work when he initially sold it. (Abbott Labs bought the work in 1960 from art dealer Albert Landry, who obtained it from the estate of Stieglitz.)

But despite Feinberg’s efforts to diminish the credibility of Abbott Labs’ claim, judge Schofield rejected her overtures.

The trial included testimony from the highly respected forensic analyst Jamie Martin, a key witness in the high-profile Knoedler Gallery forgery scandal.

Court papers note a number of potentially important witnesses who are deceased. Duncan and Feinberg both died in 2019, and several of Abbott Labs’ former attorneys also died in the period since the forgery was discovered in 2016.

What’s more, American art expert and gallery owner John Driscoll, who had been deposed in the case, died in April from the coronavirus. Lastly, Luciano Liparini, an artist identified as the possible forger of the fake Hartley, died more than 20 years ago.

“Despite the passage of time and unavailability of some witnesses and other evidence, plaintiff has met its burden of proving that it holds superior title to the painting,” Judge Schofield wrote.

After the 1987 theft, Duncan allegedly sold the work to a buyer with a falsified story, claiming he had acquired it from a person who brought it to him for an appraisal. He said it had previously been held by the H.V. Allison Gallery in New York.

Abbott Labs is actively investigating the whereabouts of several other missing works and attempting to recover them.