Jeff Koons’s Hanging Heart with the image of the painted wall behind it.

Image: via Kristin Kraemer on Instagram.

The campaign by ISIS to erase history in Palmyra is only the latest chapter in the long story of attacks on culture by zealots. Such a narrative could begin in 7th century Byzantium when the emperor Leo III banned the use of images. Destruction was widespread. There was a second period of Iconoclasm the following century. Fast forward to the slashing of Velazquez’s The Rokeby Venus in 1914 by Mary Richardson, a British suffragist who later ran the Woman’s Section of the British Union of Fascists. Or Mao Zedong’s Red Guards who prefigured the ISIS program in the 1960s.

While such grim zealotry continues, there is a new vandalism that is fueled by energies which are very specific to our time.

Our infantile empathy-deficient culture of narcissism plays a part. Take, for example, the two young California women who scratched their initials into the Roman Colosseum in March so as to pose for—well, of course—a selfie. Mostly though, the spike in incidents of artwork vandalism is a direct reaction to what’s going on within the art world itself, namely our media-drenched Cult of Creativity, Art Stardom, and the ritual chanting of auction figures.

The damaged corner of Mark Rothko’s Black on Maroon (1958).

Consider Vladimir Umanets, the Russian artist, who wrote a message in black ink in a corner of Mark Rothko’s Black on Maroon in the Tate Gallery in 2012. “I believe that if someone restores the piece and removes my signature the value of the piece would be lower but after a few years the value will go higher because of what I did,” Umanets, a co-founder of his own art cult, Yellowism, told Ben Quinn of the Guardian soon after the event.

Umanets did a year and a half in jail, and, after his release, apologized for the action in a self-righteous written piece, also in the Guardian. But he took care to reference Marcel Duchamp and fingered the art market as the real villain.

He also made plain that the action wasn’t about Rothko “whose work and ethos I greatly admire.” He added “I would have done the same had the artist been Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin. It was a spontaneous decision and nothing personal.” But often vandalism is specific, serving as a kind of assassination. So the target matters, and the bigger, the better.

“I thought by killing him I would acquire his fame,” said Mark Chapman, who gunned down John Lennon. Amongst stuff thrown at the Mona Lisa, for instance, has been acid, a rock, and a mug bought in the Louvre gift-shop.

In 2012, a young man was caught on an iPhone spray-painting an image of a bullfighter, a bull, and the word Conquista on Woman in a Red Armchair, a 1929 Picasso canvas in the Menil Collection, Houston. The gallery-goer posted the video to YouTube and the tagger, Uriel Landeros, a wanna-be artist, was tracked to Mexico. He surrendered to the US authorities and his lawyer announced that Landeros wanted the criminal mischief charges dropped because “what he did to the painting was not criminal mischief, it was an artistic statement, an expression, much like graffiti art is.”

He got two years in prison. But, before going in, he was given his own show by James Perez, a Houston gallerist, who let it be known that he considered that Landeros was an “activisit” not a vandal. He told AP that “it made me happy that someone could evoke this kind of emotion in people.” “It’s just taking something and making it your own,” he added. “I like what Uriel did. That makes it yours.” There has never been a great comedy about the art world, let alone a convincingly biting satire. The art world simply does way too good a job at satirizing itself.

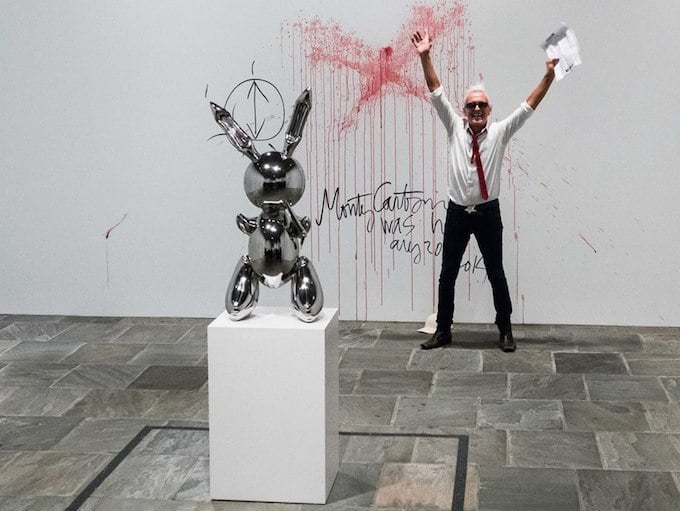

It was almost predictable that works by Jeff Koons would have been the target of not one but two episodes of vandalism at the Whitney last year—Mannerly onslaughts, at that, in that neither protester touched a work, just the walls. On August 20, Istvan Kantor (aka Monty Cantsin) splashed a large red X in his own blood on the wall behind the Rabbit aka The Brancusi Bunny.

Istvan Kantor with Jeff Koons’s Rabbit.

Image via Antoine S. Lutens on Facebook.

On October 19, Christopher Johnson was arrested for writing “pprriceless” in black paint on the wall behind a purple version of Hanging Heart.

In November 2007, a Koons Hanging Heart (a work from the artist’s Celebration series, which comes in an edition of five) fetched $23 million, making it the most expensive work of art sold at auction at the time. In 2013, a Balloon Dog, from the same series, went for $58.4 million. Rabbit is considered the central work in the series.

I don’t know Johnson but have known Istvan Kantor for some years. A Mail artist and a member of a group, Neoism, in which he took the name “Monty Cantsin,” he has been using his own blood in actions since 1989. After his arrest, he was taken by van to New York Presbyterian, one police car driving in front and one behind, while a psychiatric nurse asked such questions as “Would you like to kill Jeff Koons?” and “Would you like to blow up the Whitney?” He answered “no” to both.

“I was diagnosed as having a narcissistic personality disorder,” he told me about his stay at the hospital. “That’s very funny. All artists have narcissistic personality disorders. It was a very cool experience.”

Why had he targeted Rabbit? “It’s not that I hate Jeff Koons,” he said. “I like his art actually. It was about the corporate take-over and the money mafia in the art world. That’s what the intervention in the Whitney was about.”

He was more explicit in a letter he sent me. This was headed Supreme Gift, and addressed to Jeff Koons at the Whitney. In this, he wrote to Koons of “my high esteem of your exceptional work,” describing himself as “a convicted heretic art-criminal banned from most museums.”

The “Supreme Gift,” as per the letter, was the use of six vials of his own blood. As further commentary, a narcissistic whim, or both, he valued this at $60 million.