People

Meet the Brooklyn Puppet Designer Behind the Fantastical Olympics Opening Ceremony

Nicholas Mahon has worked for the Jim Henson Company and Blue Man Group.

Nicholas Mahon has worked for the Jim Henson Company and Blue Man Group.

by

Sara Roffino

When hundreds of millions of people tuned in to watch yesterday’s Olympics Opening Ceremony in South Korea on Friday, they were greeted by a cast of fanciful tigers, dragons, and birds. It may have been the most-watched puppet show in history. But for Brooklyn-based puppet designer Nicholas Mahon, that five-minute performance represented a year of hard work.

Inside the $78 million temporary stadium in Pyeongchang, 85 puppets were brought to life by 100 volunteer puppeteers. They served as the introduction to the two-hour ceremony, which followed the story of five Korean children as they learned about the history of Korea and the true meaning of peace. In addition to the viewers at home, more than 35,000 intrepid fans stood in below-freezing temperatures to witness the spectacle in person.

“The Land of Peace” segment during the Opening Ceremony of the PyeongChang Games. Photo: Jamie Squire/Getty Images.

One of the dozens of creatives behind the puppet show is Canadian-born Mahon, who has been working from a small nook in his Brooklyn apartment to oversee the design, fabrication, and activation of the monumental figures. He began working on them a year ago, when a Korean design team presented him with the first pencil-on-paper drawings of the characters they wanted him to bring to life.

“My role in this project was to look at the drawings and then to translate their lines into real life and figure out the construction method of these puppets,” Mahon tells artnet News. “It’s a matter of figuring out the materials, where the joints should move, and how they should move. The whole philosophy behind puppetry is about lending your soul to an inanimate object so it can seem alive.”

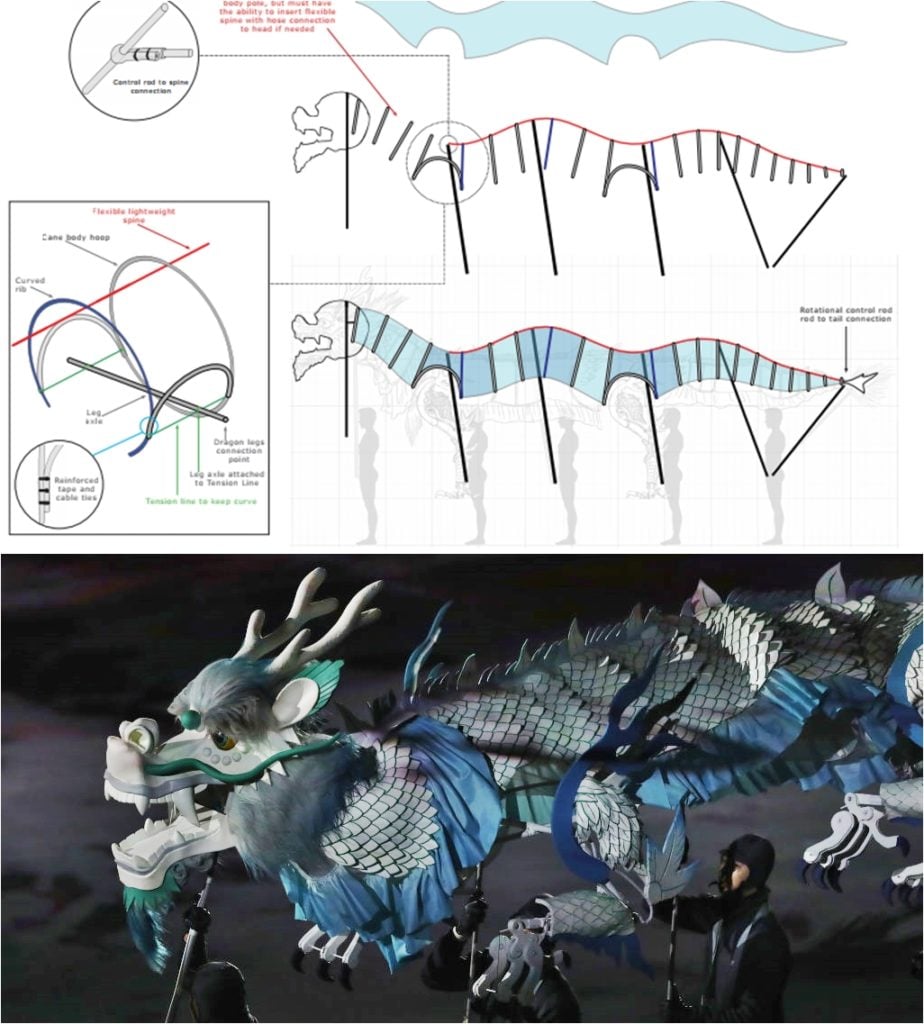

Top: Schematic for the Dragon Puppet, courtesy of the International Olympic Committee. Bottom: The Dragon Puppet at the Opening Ceremony in Pyeongchang.

The puppets were made from aluminum frames with padded foam cladding that was then covered with handmade Korean paper. Though the process combines traditional and contemporary Korean fabrication techniques, the puppets were built by a team in Malaysia over the past several months.

The monumental characters—some up to 15 feet long—include animals and figures from Korean folklore, such as a dragon, a man-bird, and a giant white tiger. Their designs were inspired by traditional Korean paintings. “We took those wispy brushstrokes from painting and made the wisps into three-dimensional foam pieces that add to the movement of the tiger,” Mahon notes.

Detail of the lion puppet making its debut at the Winter Olympics. Image courtesy of the International Olympic Committee.

A team of six people was required to manipulate the tiger alone—and many of them had never before worked with puppets. Because of the scale of such ceremonies, organizers often turn to volunteers. “In this case, there are a lot of students and soldiers,” says Mahon, who also coached the puppeteers on how to move inside the costumes.

“I really encouraged them to play around and see what they can discover on their own,” he says. “Play is a really important part of the process.”

How does one become a professional puppet-maker? Mahon grew up in a small Quebecois village, where, like generations of children before him, he became enamored of Sesame Street. “There wasn’t a lot of cultural stimulation around, but Sesame Street brought culture into my living room and first piqued my interest in puppets,” he recalls.

It wasn’t until his early twenties that he considering pursuing the job professionally.

The process of constructing the puppets featured at the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in Pyeonchang. Image courtesy of the International Olympic Committee.

After college, where he studied art, animation, and theater design, Mahon met Portland-based master puppeteer Michael Curry, and the two developed a close relationship. Curry invited him to come work in his studio, where he stayed on and off for 10 years before moving to New York and taking on freelance clients such as the Jim Henson Company and Blue Man Group.

“What I love about puppets is that it’s about being a great sculptor, but you’re also a painter, and you need to be able to sew, and to know about mechanics and materials and even, ideally, you’re also kind of an actor, and you think about story,” Mahon says.

In 2015, Curry asked Mahon to collaborate as artistic directors of the European Games in Baku, Azerbaijan—his first foray into the international ceremony world. He has since overseen other projects in Baku as well as Abu Dhabi’s Mother of the Nation Festival in 2016.

Opening Ceremony of the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Photo: Richard Heathcote/Getty Images.

The process of building a ceremony that will captivate people around the globe isn’t easy. “You have to play to two different audiences: it’s theater for the tens of thousands of people in the stadium, but there are also millions of people watching remotely and those forms require different ways of moving and communicating and idea,” Mahon notes.

The job is also not for the sentimental. Like the Pyeongchang stadium itself, which will be used for a total of four events before it is demolished, the fate of the puppets is somewhat bleak. Sometimes, ceremony props and puppets are re-purposed for other events or end up in museums. But often, the puppets are simply placed in storage after their debut performance.

Child actors perform with artists handling a white tiger puppet during the opening ceremony of the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Photo: Jamie Squire/Getty Images.

“It is a little heartbreaking,” Mahon says. “The job of the puppeteer is to put our souls into these things, so to put them away in a box is hard on the little puppeteer’s soul.”