Artist and activist Michelle Hartney quietly staged a performance at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on Saturday night, calling on the august institution to reconsider its role in glossing over the sexual misdeeds of some of art history’s biggest names.

Hartney affixed new wall labels next to works by Paul Gauguin, who moved to the South Pacific and took several native teenage girls as wives, and Pablo Picasso, who in his 40s had an affair with the teenage girl Marie-Thérèse Walter. Next to Picasso’s portrait of Walter, The Dreamer, Hartney posted a label with her own name and the work title Performance/Call to Action.

In the description, she quoted comedian Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix special Nanette: “The history of western art is just the history of men painting women like they’re flesh vases for their dick flowers,” said Gadsby, who went on to quote Picasso as saying, “‘Each time… I leave a woman, I should burn her. Destroy the woman, you destroy the past she represents.’ Cool guy. The greatest artist of the twentieth century.”

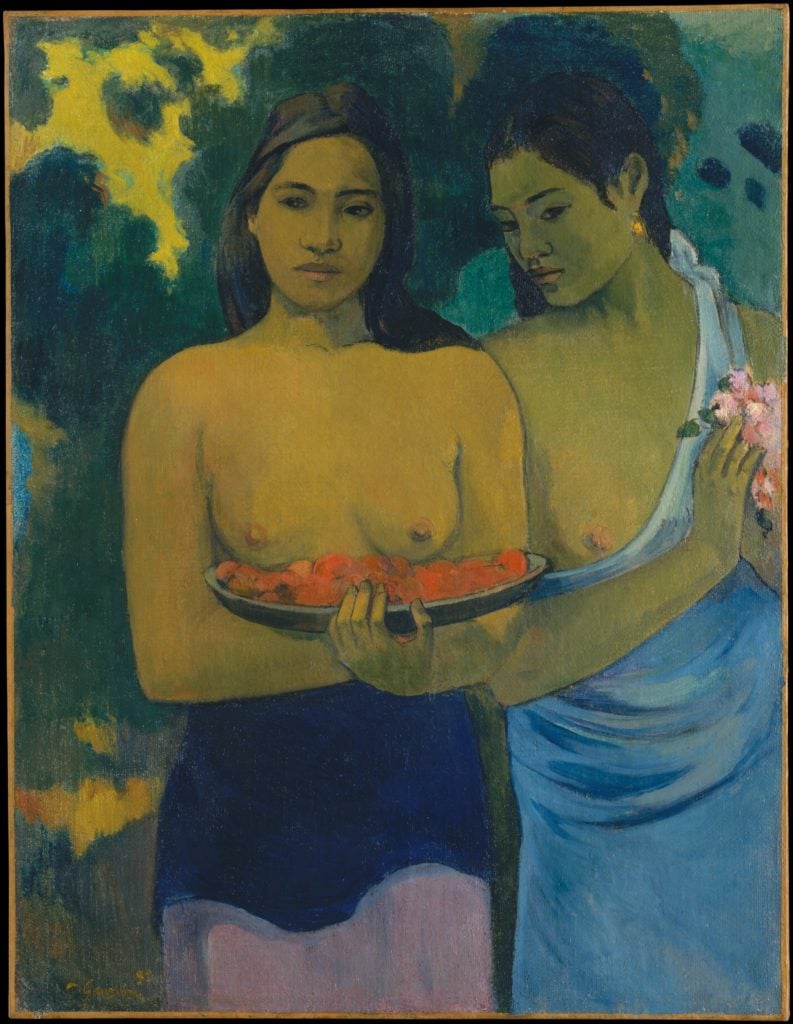

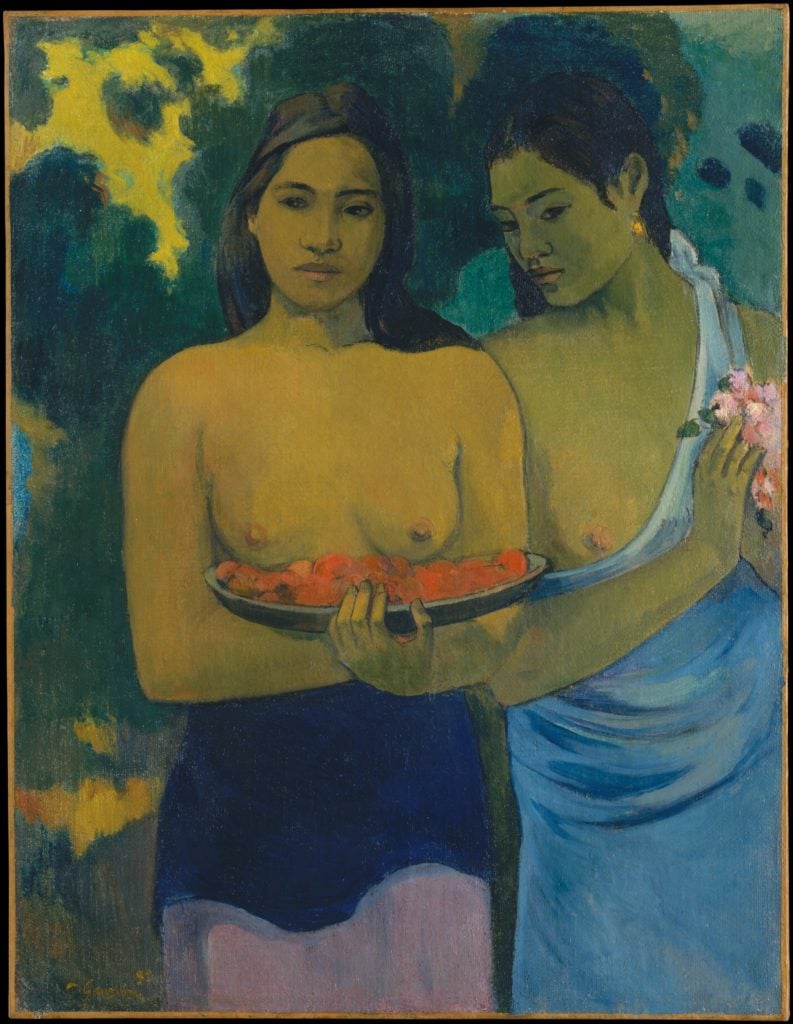

Alongside Gauguin’s Two Tahitian Women, Hartney posted an excerpt from a February article by Roxane Gay, “Can I Enjoy the Art but Denounce the Artist?”

“We can no longer worship at the altar of creative genius while ignoring the price all too often paid for that genius,” Gay wrote. “In truth, we should have learned this lesson long ago, but we have a cultural fascination with creative and powerful men who are also ‘mercurial’ or ‘volatile,’ with men who behave badly.”

“I think people are coming around to the idea that providing historical context doesn’t take away from a work of art,” Hartney told artnet News. “Museums almost infantilize viewers by thinking they can’t handle having this biographical information. What’s wrong with with having an aesthetic opinion about a piece of artwork and other feelings about the artist himself? I look at Gauguin’s painting on a aesthetic level, and they are amazing and beautiful. But I also think he was pretty horrible to take three teenage brides. I can have those two feelings about it.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bpw4PQFFPWw/

A representative for the Met declined to comment on the protest, other than to say that Hartney’s labels were removed as soon as they were discovered by museum staff.

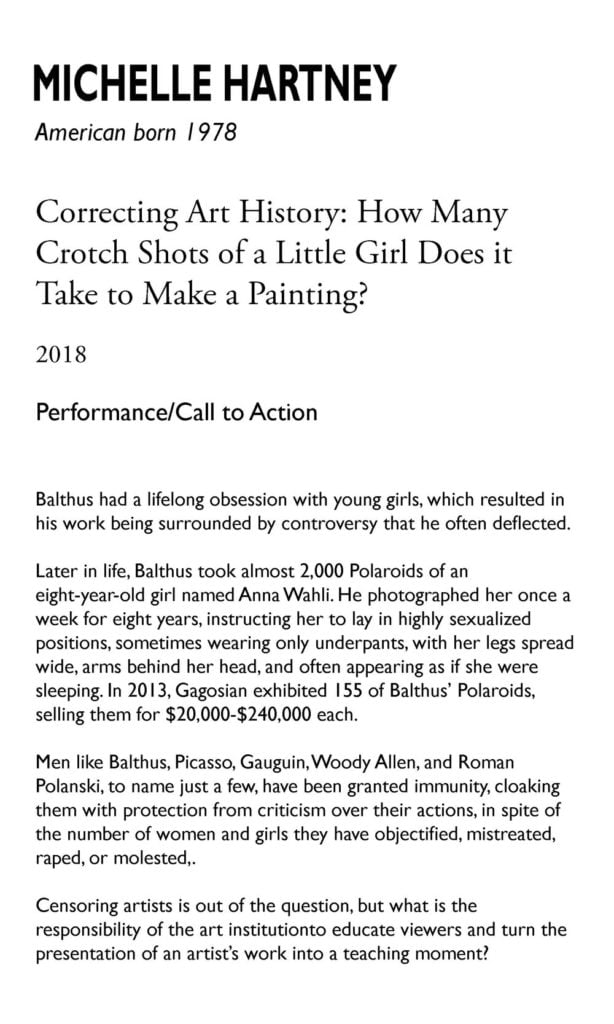

This isn’t the first time Hartney has addressed this issue. Earlier this year, she staged a similar protest at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, her alma mater, appending additional wall texts next to the display of Balthus’s painting Girl With Cat.

Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women (1899). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hartney titled her response to the work Correcting Art History: How Many Crotch Shots of a Little Girl Does It Take to Make a Painting?, and offered a description of the artist’s “lifelong obsession with young girls.” She pointed specifically to his 2,000 Polaroids of a young girl named Anna Wahli, sometimes clad only in her underwear, taken over a period of nine years beginning when she was eight. (Unlike with Gauguin and Picasso, this was in the 1990s.)

“Some people could consider those Polaroids child pornography,” Hartney said. “And Gagosian was selling them for $20,000 each. So far they have sold at least 20, the gallery told me.”

Michelle Hartney put this label up next to a Balthus painting at the Art Institute of Chicago earlier this year. Photo courtesy of Michelle Hartney.

The school told Hartney that it would revoke her alumni privileges if she ever did it again. “On one level I get it, but on the other hand, my school is threatening to punish me for a piece of performance art,” she said.

Hartney was inspired in part by a viral petition late last year protesting a provocative Balthus painting at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. As a debate over censorship swirled, the Washington Post‘s Philip Kennicott rejected calls for the painting’s removal, or for the addition of a warning label noting that “some viewers find this piece offensive or disturbing, given Balthus’s artistic infatuation with young girls,” as the petition suggested.

Balthus’s Thérese Dreaming (1938) sparked a petition demanding its removal at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Even that would be a concession too far,” Kennicott wrote. “By that standard, the museum might have to include hundreds, if not thousands, of warning labels, and not just for works made by heterosexual men with an erotic interest in girls.”

As the #MeToo moment picked up steam earlier this year, Kennicott wasn’t alone in his concern that the pendulum was in danger of swinging too far. “At some point you have to ask yourself, is the art going to stand alone as something that needs to be seen?” Jock Reynolds, the director of the Yale University Art Gallery in Connecticut asked the New York Times. “Pablo Picasso was one of the worst offenders of the 20th century in terms of his history with women. Are we going to take his work out of the galleries?”

Hartney maintains that she is staunchly anti-censorship, but that museums are doing the public a disservice by refusing to acknowledge the ugly truths about some of the artists in their collections. In February, artist and activist Emma Sulkowicz raised similar concerns with a performance protest in front of Chuck Close’s paintings at the Met and MoMA.

“I don’t want to preach to museums and say ‘I know the answer,'” Hartney says, “but I think maybe trying a different way of presenting work could be interesting. It could educate even more, which is what these institutions aim to do.”

Balthus, Girl With Cat (1937). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, ©Balthus.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.