On View

As Egon Schiele Centenary Exhibitions Open, Museums Address Abuse Allegations Against the Artist

The MFA Boston has revised wall labels to address his alleged mistreatment of women.

The MFA Boston has revised wall labels to address his alleged mistreatment of women.

Museums around the world are gearing up to celebrate the centenary of the death of Egon Schiele (1890–1918). But in light of the art world’s ongoing reckoning with the #metoo movement, curators are having to ask themselves new questions about the Austrian artist, who faced criminal charges in 1912.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which opened an exhibition of work by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) and Schiele last week, has produced new wall labels that directly address the charges against the younger of the two Austrian artists. When he was 21, Schiele was arrested for the alleged kidnapping and statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl. He was later acquitted on both charges, but spent 24 days in jail, and was eventually found guilty of “immorality” because the girl had seen some of the nude works hanging in his studio.

The labels appear in the exhibition “Klimt and Schiele: Drawn” (February 25–May 28, 2018), which is drawn from the holdings of Vienna’s Albertina Museum and examines how the two Austrian artists depicted the human body.

“Wall labels in the exhibition acknowledge that Schiele has been a part of the current conversation, and don’t shy away from these issues,” a representative for the museum told artnet News. “Instead, the interpretation creates context for visitors, including facts about the artist’s life and the reception of his works—then and now.”

The wall text notes that “recently, Schiele has been mentioned in the context of sexual misconduct by artists, of the present and the past. This stems in part from specific charges (ultimately dropped as unfounded) of kidnapping and molestation.” It also notes that Schiele “has long had a reputation as a transgressive at society’s edges.” Elsewhere, the wall text includes a section subtitled “Schiele: The Stuff of Scandal.”

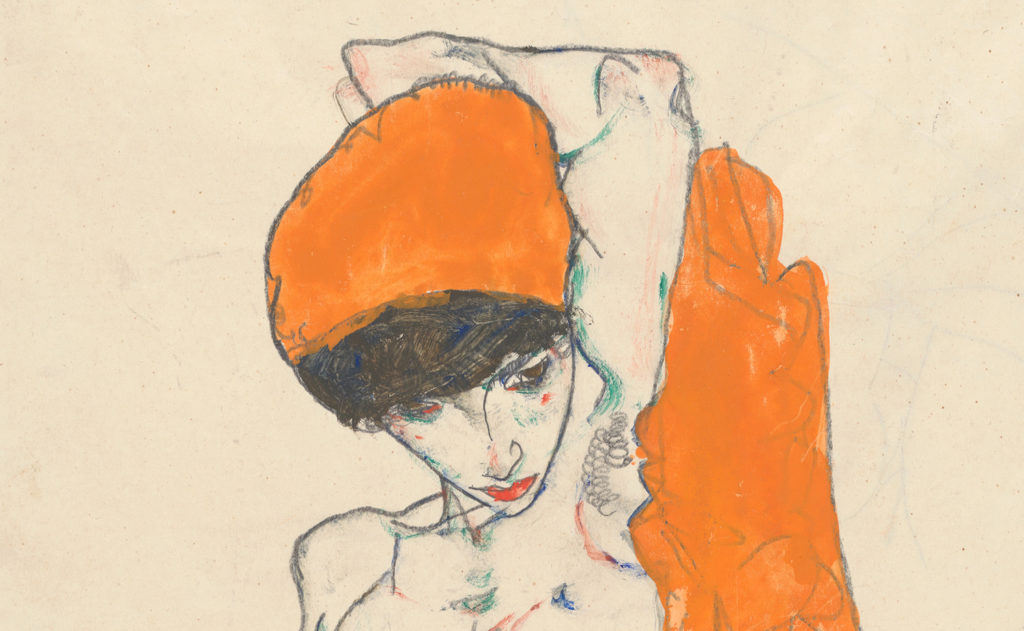

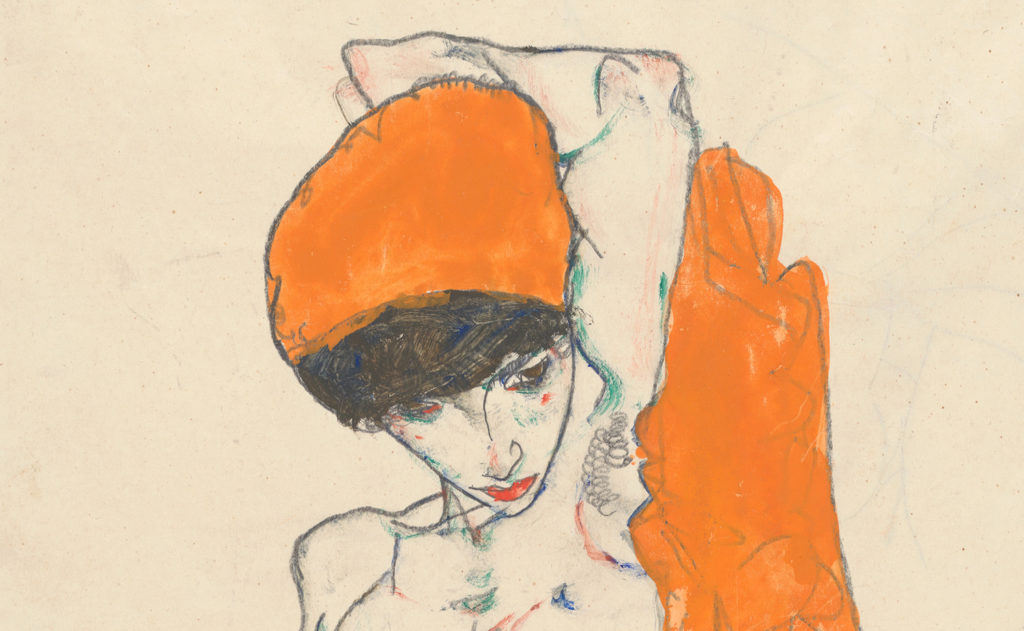

Egon Schiele, Portrait of a Girl (c. 1907). Courtesy of the Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is still mulling over how it might address the issue in a forthcoming exhibition. This summer, the Met will present a rarely seen collection of erotic artwork by Klimt, Schiele, and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)—another artist who has been accused of mistreating women—in “Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection” at the Met Breuer (July 3–October 7, 2018).

“Like other museums, the Met reappraises its collection in light of new research and interpretations,” Sheena Wagstaff, the Met’s chairman of Modern and contemporary art, told artnet News in an email. “This work takes the form of publications and object labels, as well as exhibition wall texts.”

In January, the New York Times questioned whether museums should consider informing viewers when artists on display—including Schiele and Picasso—have been accused of sexual harassment or assault. The performance artist Emma Sulkowicz stood nearly naked in front of work by Picasso and Chuck Close at New York museums in a protest inspired by the Times piece, and would have targeted Schiele too, but could not find any of his work on view in New York.

Emma Sulkowicz’s protest performance, with Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo courtesy of Sangsuk Sylvia Kang.

As museums mull how to address these issues in their presentation of work by historic artists, one thing is clear: the work itself is here to stay. As the MFA so diplomatically put it, “we encourage our visitors to draw their own conclusions, while recognizing the range of responses Schiele’s works can elicit: from empathy, to discomfort, to inspiration among subsequent generations of artists.”

See more erotic works by Schiele and Picasso from the MFA Boston exhibition and the Met’s Scofield Thayer collection below.

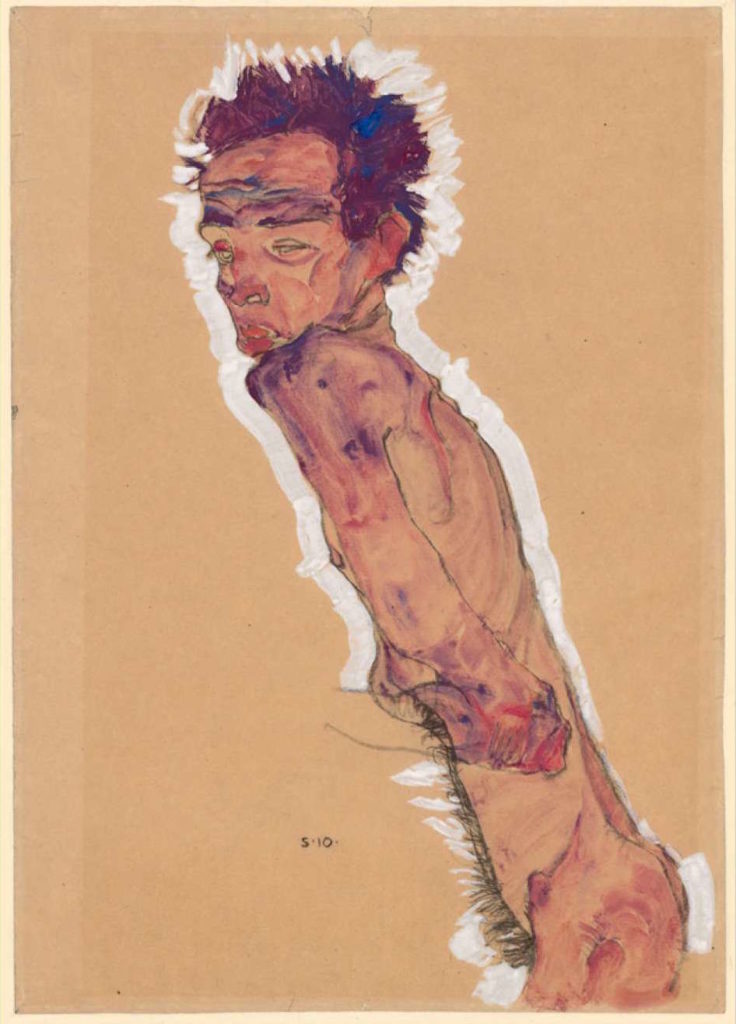

Egon Schiele, Nude Self-Portrait (1910). Courtesy of the Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Egon Schiele, Portrait of the Artist’s Sister-in-Law, Adele Harms (1917). Courtesy of the Albertina Museum, Vienna.

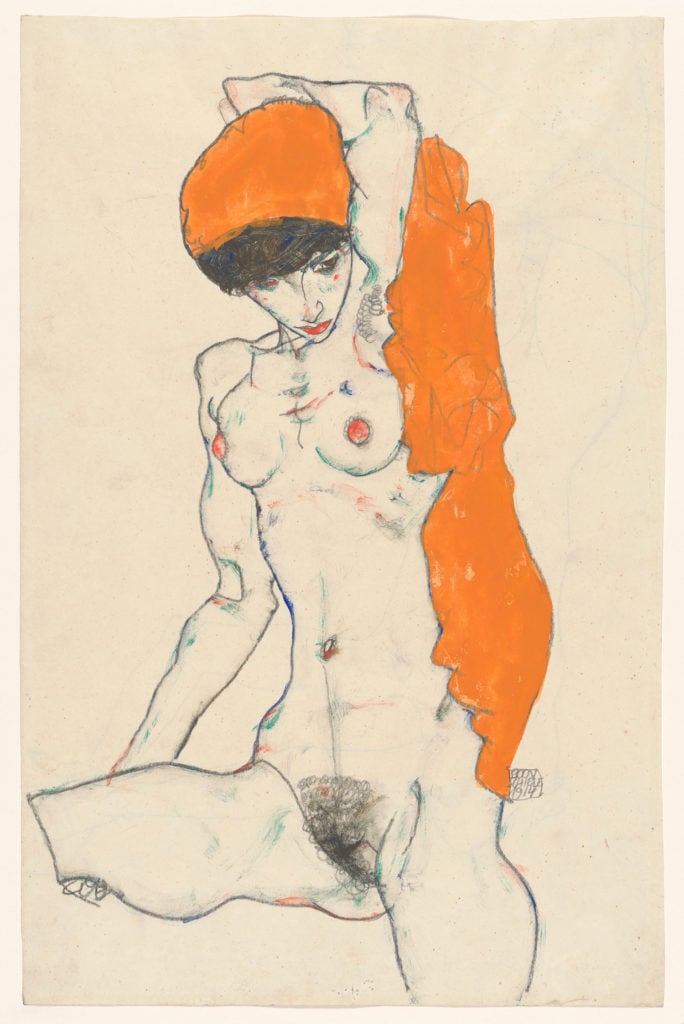

Egon Schiele, Standing Nude with Orange Drapery (1914). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982.

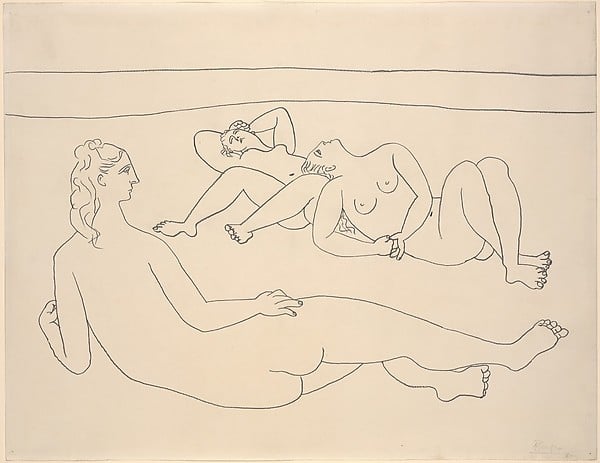

Pablo Picasso, Three Bathers Reclining by the Shore (1920), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. © 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

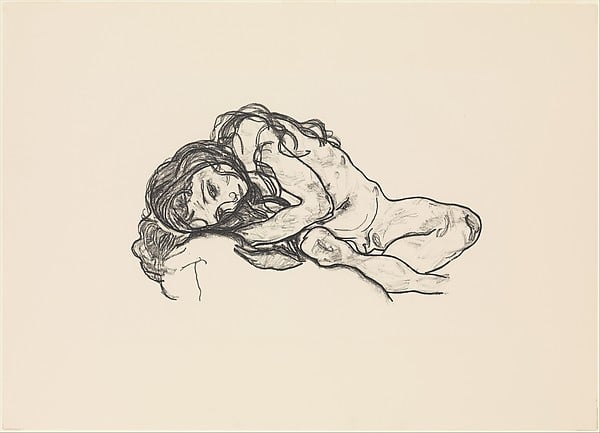

Egon Schiele, Girl (1918), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

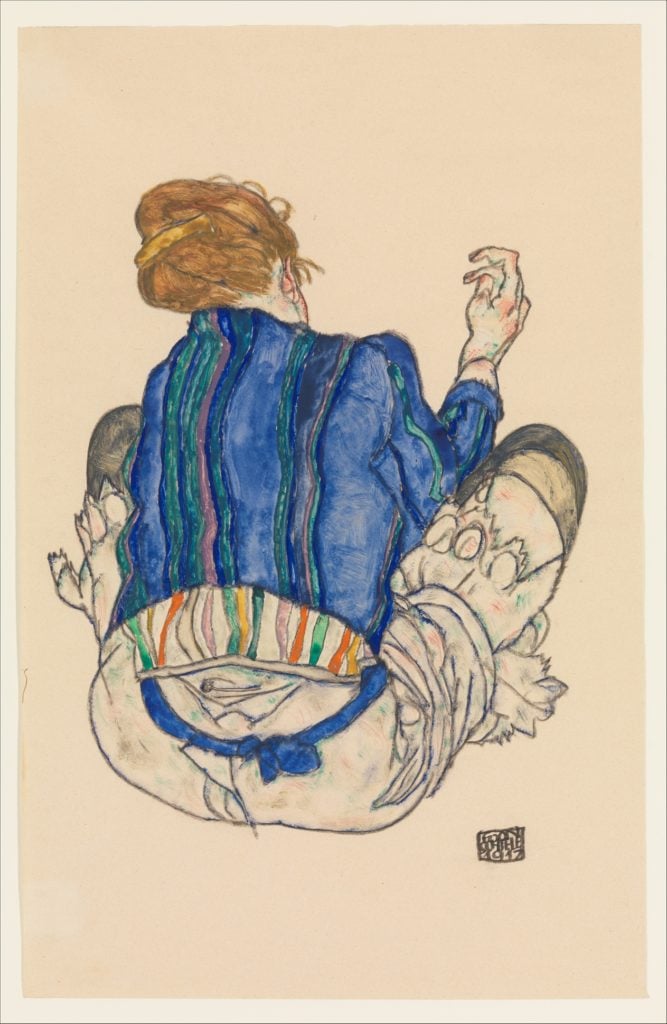

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman, Back View (1917), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

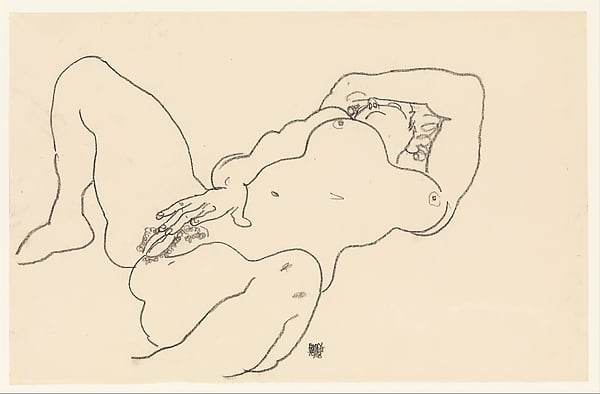

Egon Schiele, Reclining Nude (1918), donated to the Met by Scofield Thayer. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.