In Diego Velázquez’s cryptic Las Meninas (1656), a portrait session appears to be in progress. The young Infanta Margaret Theresa, King Philip IV of Spain’s first child, is resplendently posed in the center of the frame, encircled by her entourage and a dog. Velázquez himself, brush and palette in hand, is standing off to the side and gazing at a large canvas, suggesting that he is painting the scene we are seeing. Or maybe not. The only glimpse we get of the depicted canvas, alas, is its reverse.

But for artist Miguel Ángel Blanco, Las Meninas invited a tantalizing contemplation of a rarely seen aspect of paintings. That thought has led him to curate a new exhibition at the Prado Museum in Madrid, which makes the case that a work of art is more than what’s on its face.

“On the Reverse” features about 100 works by the likes of René Magritte, Vincent van Gogh, Goya, Sophie Calle and Michelangelo Pistoletto—pulled from the collections of the Prado and 29 other museums—displayed so their backs face the viewers. The rears of these canvases reveal whole other realities: some bear the artist’s sketches or seals, some are stamped with reminders of the work’s provenance, and others contain whole other paintings.

A possible self-portrait, attributed to Orazio Borgianni (1600–10). Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

“Works of art are three-dimensional,” the museum’s director, Miguel Falomir, told The Guardian. “When we focus solely on the image, which is a reproduction of a given moment frozen in time, we get some information, but we miss a lot when it comes to everything that the work means as an object.”

The show is split into 10 chapters that variously explore the symbolism of the stretcher, painted trompe l’oeils depicting the rear of works, and the cuts and folds made to a canvas—still visible on its back—to adapt it to new locations or functions.

Most intriguing are the sections exploring how the backs of paintings serve as extensions of its face, or the artist’s creative process. For instance, Annibale Carracci’s The Ecstasy of Mary Magdalene (1585–1600) has on its back drawings etched in black chalk by the Italian painter’s students. The reverse of a Vicente Palmaroli canvas, meanwhile, is jotted with the artist’s landscape and figure notes.

Martin van Meytens, Kneeling Nun (obverse) (c. 1731). Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Martin van Meytens, Kneeling Nun (reverso) (c. 1731). Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

On view in a segment focused on two-sided paintings is a striking work that goes to the heart of the show. In Kneeling Nun (c. 1731), Swedish-Austrian court painter Martin van Meytens captured his titular figure bent over her devotional book in mid-prayer. Cheekily, on the reverse, he painted the same nun from the back, her habit pulled up to reveal her bare bottom.

“It’s an excellent example of a pornographic image half-hidden on the reverse that belonged to the Swedish ambassador to Paris, who kept it hidden and only showed it to special guests,” Blanco explained.

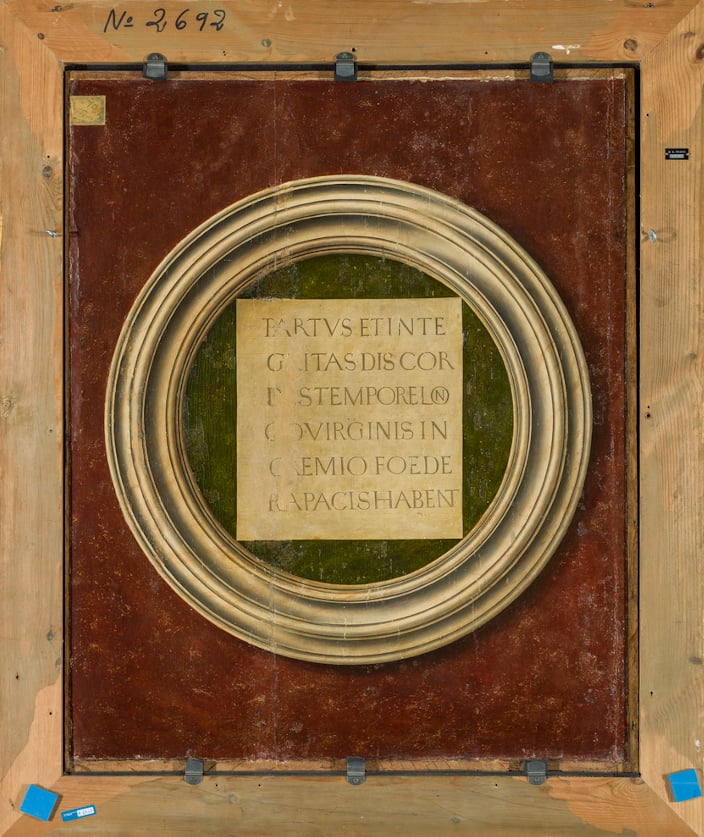

Vik Muniz, Verso (Las Meninas) (2018). Courtesy of the artist and the Elba Benítez Gallery

Las Meninas also shows up here. No, not the actual canvas, which is on view in the Prado’s Villanueva building, but a faithful reproduction of its back. The facsimile was created over a period of two years by Vik Muniz, who meticulously matched the dimensions and materials of the rear of this Velázquez work. The Brazilian artist even reproduced the same stains and rivets on the pinewood body, as well as the small plaque bearing the Prado’s inventory number.

“The exhibition aims to remind us of something that I think Velázquez would also want us to consider if he were here,” said Falomir, “which is that art—and painting in particular—isn’t just about the image itself.”

See more images from the exhibition below.

Installation view of “On the Reverse” at the Prado Museum. Photo © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Artist in his Studio (c. 1628). Boston, Museum of Fine Arts. Zoe Oliver Sherman Collection given in memory of Lillie Oliver Poor. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Sketches of figures on the reverse of Annibale Carracci, The Ecstasy of Mary Magdalene (1585–1600). La Coruña, Museo de Belas Artes da Coruña, depósito del Museo Nacional del Prado. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Salomon Koninck, A Philosopher (reverse) (1635). Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Zacarías González Velázquez, Two Fishermen, one with a Rod and the other seated (reverse) (1785). Madrid, Cuartel General del Ejército, depósito del Museo Nacional del Prado. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Installation view of “On the Reverse” at the Prado Museum. Photo © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior with the Artist’s Easel (1910). Copenhagen, SMK, National Gallery of Denmark. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

Anonymous artist, The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John / Christ presented to the People (reverse) (c. 1500). Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. Courtesy of the Prado Museum.

“On The Reverse” is on view at the Prado Museum, C. de Ruiz de Alarcón, 23, Madrid, Spain, through March 3, 2024.

More Trending Stories:

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments

Gerhard Richter’s Abstract Alpine Landscapes Will Converge at a Three-Venue Survey in St. Moritz