People

Author Roxane Gay, Who Loves Art But Dislikes the Art World, Has Some Advice for Galleries: ‘Stop Being Terrible’

The writer spoke to Artnet News about collecting, navigating the art world as a newcomer, and more.

The writer spoke to Artnet News about collecting, navigating the art world as a newcomer, and more.

Roxane Gay has run out of wall space. The award-winning author and essayist, for whom art collecting is a newish venture, has, in just three years, amassed a formidable collection that inspires and delights.

Last week, I called Gay at home to talk about her collection, which she has begun posting about occasionally on Twitter, where she’s also amassed a cult following of 830,000. Her online presence, her books Bad Feminist and Hunger, and her approach to collecting all share a keen sense of observation and an appreciation for strong points of view.

Below, Gay opens up about toxic gallery culture, the pressures placed on creatives of color, Seth Rogen’s ceramics, and what visual art does and doesn’t do for her writing.

Tell me about the beginnings of your relationship with visual art. Did you look at art a lot growing up?

I did. My mom was very big on cultural education and even though we never lived in cities, we always lived reasonably close to cities. When we lived in Virginia, we went to D.C., when we lived in New Jersey we went into New York, when we lived in New England, we went to Boston. So I grew up around art and my parents collect Haitian art. I remember thinking, “This is beautiful” or “this is weird” or “I could do that.” [laughs] A lot of times, we think we can do whatever “that” is, but the reality is that we don’t, and art exists for a reason; it’s a practice, and it always made me think.

When and why did you begin collecting it?

I’m very new to art collecting. I got into it because my wife, [writer, designer, and podcast host] Debbie Millman, is a very big collector. Like many people, I just thought that art went for the millions of dollars that you hear about in the news. But she showed me that there are lots of price points between zero and Basquiat. I started to explore and acquire pieces. And now it’s out of control.

A work by Caroline Wells Chandler in Gay’s home. Photo courtesy Roxane Gay.

What do you like to collect?

I prioritize work by Black artists, and then women artists and queer artists and artists of color. And then the very, very last thing I collect is white men. I think I have one piece by a white guy. I mean, they’re fine… actually no, I have a couple pieces, but those are my priorities.

It all started when we were in Paris on vacation and we went by a gallery on a walking tour that had this beautiful textile work by Caroline Wells Chandler. And I couldn’t remember the name of the artist or gallery, so I spent months trying to find it on Google Maps and calling up every gallery. I found out who they were and where to find them, so the first real piece I bought ended up being an amazing piece of theirs called Schoolbois. From there, it sort of snowballed. I have two great pieces from Alexandra Grant—we did a work trade—and then I have a piece by Jesus Rafael Soto, whose work I love. I have a Jenny Holzer sculpture. I have four pieces by Mickalene Thomas, who I think is excellent. I have some Marilyn Minter. I have a Barbara Kruger. Edwin Schlossberg and a Julian Opie. So those are the white guys… I actually just got a William Kentridge, who’s also a white guy, now that I think of it.

I have a couple Julie Mehretus. I have a Kahlil Robert Irving. I just got a Brenna Youngblood. I’m very excited about that one, and trying to figure out where I’m going to put it. I’m kind of out of wall space, but I will figure it out. And my wife got me a Jenny Saville, who I’m a fan of. She also got me a Warhol print of an elephant, because I love elephants. There’s this great English artist named Emma Hopkins—I just got a piece from her that’s really cool. I have a Bisa Butler, who’s amazing. I love, love, love her work. And then I have a work by a young woman, Sadie Barnette, who renders pages from her father’s FBI files. I have a piece from Christo and Jeanne-Claude. I have a couple Lichtensteins—that’s my number one artist, even though I know it’s cliché. Whatever. I have some Hans Haacke. Tracey Emin. Tschabalala Self. I have a great piece by Yinka Shonibare, who’s lovely.

That’s an incredible collection.

It is. I mean, I’m proud of it. I just like what I like. And I get it, in some ways it’s an investment, but I actually don’t intend to do anything with them but display them. They just make me happy.

I think that’s the best reason to collect.

I do, too.

I saw—I think—that you got a vase by Seth Rogen recently. Is that right?

[laughs] That is true, yes. I did.

What’s the deal with Seth, do you think? Why is there so much hype around his work?

I think that any time a celebrity can do something outside of their field and do it well, people are surprised because we tend to think that celebrities are merely what we know them for. And the reality is that he’s actually a very good ceramicist and he would be good whether or not he’s Seth Rogen. Also, he’s a guy, and at least for me, it’s like, “A man making art? Wow.” Because I tend to have a very low opinion of them. But not Seth, I think Seth’s wonderful. The work’s really good, it’s brightly colored, and I think he’s willing to put himself out there with his art despite the fact that people can be quite mean about it, which is weird. If he just wants to fucking smoke pot and make pots, let him do it. I think everyone should pursue an artistic ambition. You know, good for him.

New vase. And yes. Yes it is. pic.twitter.com/qPX2HrDn6M

— roxane gay (@rgay) March 27, 2021

I think there’s also something almost vulnerable in how he began making those little weed pots in public and how he’s grown as an artist because he’s really put himself out there by showing he’s trying to do work beyond the schtick that got him into this, and it’s also technically more ambitious. The response to that, I agree, has been interesting—people would almost prefer him to stick to the schtick.

Absolutely.

I am interested to know if you have thoughts on how galleries can reach new collectors, particularly collectors of color, more effectively.

Oh, and I just remembered—I have a work by Lorraine O’Grady. I’m so thrilled about that one.

I mean she is incredible.

She is. She really, really is.

In terms of galleries, I think that galleries can remove some of the snobbery around the gallery experience and stop acting like they don’t want to sell their art because that’s really off-putting. And for someone like me, who doesn’t know anything about the art world, when a gallery is off-putting, I just assume nothing is for sale. I’ll leave and go spend my money somewhere else. I think that attitude is really terrible. But I also think how they treat their employees is really terrible. I’m not particularly interested in spending my money in a place that exploits people. So I think just fixing themselves up would help—stop being terrible.

Consumer education would go a long way, too. I don’t think that people understand that you can acquire art from $100 all the way up to $100 million. People should talk more about prints and what prints are and how they’re not just posters. [laughs] I think talking about supporting up-and-coming artists, and how it’s not a gamble but an investment in an artist’s practice, is incredibly useful. And I think doing outreach to various communities… I think they don’t do it because they want art to have this exclusivity around it and I don’t think that’s necessary. Art should be something that everyone can enjoy, and not only in museums.

In your view and experience, how is literary gatekeeping similar or different to art-world gatekeeping?

I think there are some similarities, but not many. At least in the literary world, if you have a pen and paper, you can write and you can get your work out there. Art practices require a little bit more in terms of resources… even just to make art, supplies are quite expensive. Writing is slightly more democratized, but in terms of being able to make a sustainable living from it, there are similarities—and the publishing world is as dominated by whiteness as art discourse.

I’m thinking, too, of the advice you gave the anonymous person of color working for a classical music organization in your recent New York Times column, where you suggest they try to introduce work by classical composers of color to their colleagues and repertoire. In the wider cultural world, do you think the conversation is indeed shifting a little more toward the stories of people of color? Is that actually happening?

I think it’s happening, but I think we are doing the shift. We are not waiting for the conversation to shift to us, we are demanding the attention, as we should. It’s not happening as broadly and as quickly as we need it to, and I think that’s incredibly frustrating to a lot of people, but I think we have to continue demanding instead of waiting for these white gatekeepers to love and accept us. We have to find new ways of external validation that do not predicate themselves on white supremacy. We have to continue to support one another and make sure that we are mentoring up-and-coming writers and artists. When you achieve a certain level of success, you have to make sure you are doing everything in your power to ensure that you are not the only one in any room.

It’s obviously not the job of people of color to try and make this world fairer and more equitable, which you write about often, but you’re also candid about the fact that, in practice, change happens in the uncomfortable moments when we have to look those issues in the face and raise them time and time again. Often, it does come down to people of color to not only initiate but continue those conversations to ensure they remain in the air. How do you reckon with this in your own work as a creative person—that it’s not your job to do this work, but the work must get done and you are, so to speak, good at it?

I just try to have a sense of self-preservation in that it isn’t actually my job to do this work. My creative work has to take priority and unfortunately sometimes it doesn’t and that’s incredibly frustrating. So I have to always remind myself that someone has to do this work, but I am not the only person who has to do this work, and I do not have to do this work only. Because it’s actually just a fraction of what my creative process is. And so I just try to have a fine balance.

*Loud meowing begins in the distance*

Is that your cat?

Yeah…

Amazing.

He is just meowing intensely at the street.

Maybe something’s happening out there.

Maybe.

Two works by Julie Mehretu. Photo courtesy Roxane Gay.

Recently, you shared on social media a not-so-nice experience that you had while trying to pick up an artwork at a gallery. Could you tell me a little more about that?

It was just one of those daily microaggressions… so in the grand scheme of things, don’t cry for me, it’s fine.

I had bought a piece of art through a secondary gallery and I had told them I would be there to pick it up in the next two days, but I didn’t give a specific time. So they were expecting me broadly, but not at the specific time I showed up. And I just walked in and there was no one really at the front desk, but then I looked around the corner and there was a young woman sitting there who had watched me walk in and watched me stand there for a few minutes. It’s okay, but it was like… “Huh.” When she said, “How can I help you?” and I said, “I’m here to pick up some art,” she said, “For who?” And I was like, “Huh, alright. Of course. It certainly couldn’t be for me.”

In the end, I ended up tweeting about it, but I didn’t name the gallery because this woman was very young and this one person is not responsible for a system that does this kind of thing. I think people should be held accountable for their actions, but I do not think 800,000 people need to know who the specific person was. So later that day, I actually got an email from someone who was like, “Oh, I was reading about your experience with the gallery and I just thought, ‘Ugh those galleries are so terrible.’” And then she said, “Oh my god, I hope you weren’t picking up art at my gallery.” And it turned out I was. So she explained what happened and apologized and so that was good. Apparently, the young woman had just started working in a public-facing role and they’re not actually used to people picking up their own art, which… I still think microaggression was part of it, but I get it.

It probably didn’t help, too, when she found out you were Roxane Gay.

Oh, I don’t think she knew who I was. I’m just a writer. But you know, the explanation certainly made sense and I think it will never happen again. And that’s good.

Are there other galleries where you’ve had similar experiences? I mean there’s a sort of cold culture to galleries on the whole, especially the ones in New York, but are there any other experiences that stand out?

There was one other gallery in Los Angeles, actually, where I walked in to look at some art and they had invited me to come, but the person who had invited me wasn’t there. So I was just standing there and I literally walked around for 10 minutes while the two gallery assistants watched, went back to work, and didn’t say a single word to me. So I just left and never bought art from there.

Gallery people love to look at you and then look away.

Yeah! And like, you’re probably working here for free! It’s just like, “What are you doing, friends?” This isn’t going to get you to the promised land.

Kara Walker, Insurrectiokn! (Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On (2000). Courtesy of HBO.

You have spoken about how artists like Kara Walker and Julie Mehretu have managed to inform your own creative process as a writer. In an interview, you said that you love how Walker prioritizes Black bodies and highlights, in your words, “the absurdity of some of the things Black bodies have been subjected to.” You also said her work challenges you. I’m wondering how, exactly, on both a personal and creative level.

Well, I think her work is very provocative and very interesting. She works in caricature and she revels in the grotesqueries of racism and I love that she is willing to take risks that Black artists for many years were reluctant to do because their entry into the art world was so precarious and so tenuous that they could not take those kinds of risks. There are plenty of Black artists, to be clear, who have taken risks throughout art history, but she does it in a really cheeky way. There’s a lot of wit to her work. They’re funny to critique, but she really goes for it and I admire that about her. It certainly encourages me to go for it in the kinds of things that I do.

In that same interview, you also said that “art doesn’t ask you to just react, but to move toward something different.” I’ve been thinking about that a lot. What exactly did you mean by that?

I think, ideally, art makes you want to learn more about whatever the artist is doing and seek out other art. I think good art can be more of a door to other things than a closed room.

Can you think of a time when a visual artwork moved you toward something different?

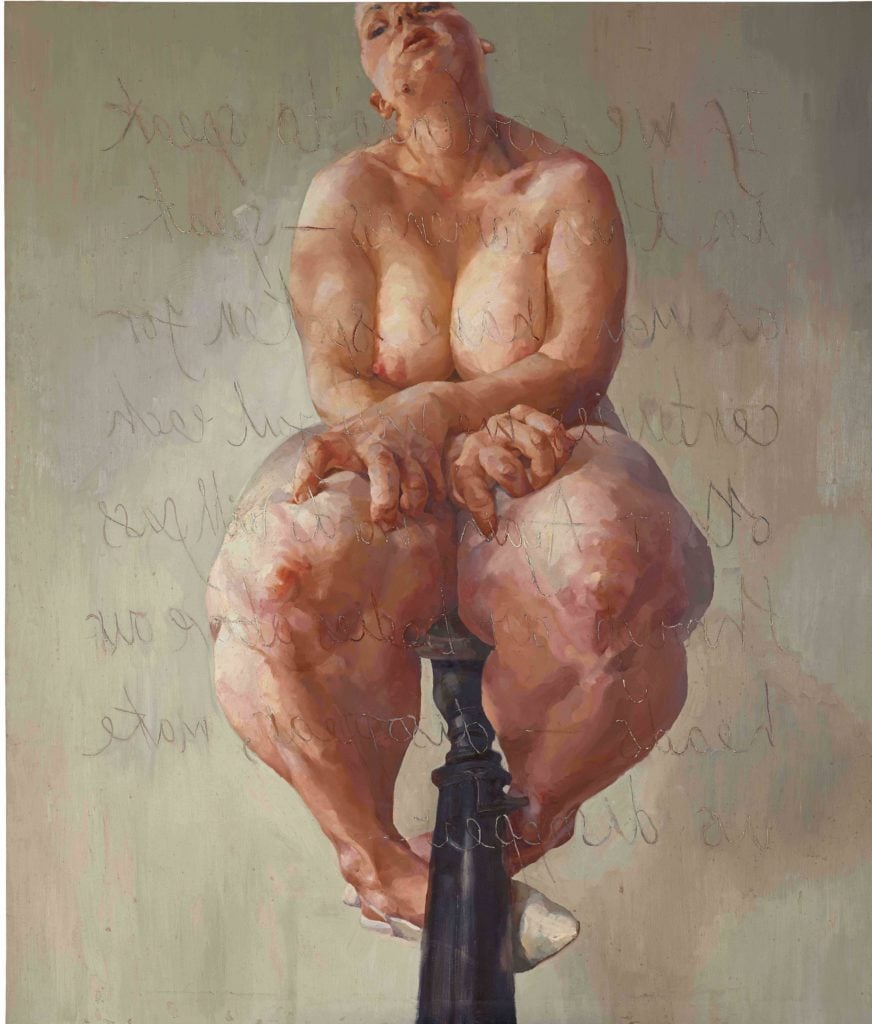

Oddly enough, the artwork that really moved me toward something different was a piece by Jenny Saville at The Broad in Los Angeles. I can’t remember the name, but it was a piece of a glorious fat woman and I just loved seeing that kind of a body on an art canvas, taking up so much space in the gallery. It was prominently featured and really well hung. That just made me think, “Yeah, you don’t actually have to hide your body.” It was a celebration and rarely do we see… We see fat tolerance, but we don’t see fat celebration. So it just reshaped some of my thinking around fat bodies.

You’ve been generous in your counsel and advice for how young writers can hone their craft to make it as true as possible, how they might use their writing for a greater good. Have you thought about how your writing advice might apply to young visual artists?

The number one piece of advice I give to up-and-coming writers is to be relentless and to have a day job until you don’t need one, because it just frees you up if you’re not stressing about how to make ends meet. And you don’t have to live in New York. I would say the same thing to a young visual artist. You have to commit and take your practice seriously even when no one else will—and for most of your career, no one else will. And that’s okay… no, it’s actually not okay, but you can still make art despite that because you have a vision and it’s great and important to execute that vision. You don’t have to do it every day, but consistency is key to developing and expanding your craft.

Jenny Saville, Propped (1992). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

I wanted to ask you about Debbie Millman, your wife, who as you mentioned is an avid art collector and also an artist and designer herself. What have you noticed about being part of a relationship between a writer and artist?

It’s great to be with someone who respects the need to make art and be creative and understands that sometimes it’s going to happen at inconvenient times, like in the middle of the night, which is when I do most of my writing. She’s so dedicated to what she does and it’s just really affirming. She’s also my number one fan—just a super cheerleader, because she knows what goes into making the work that I do and I also know what goes into her practice. So it’s very easy for me to be her number one fan.

How did you hold up creatively in 2020?

For the first part of 2020, I did not get much done creatively at all. I was like many people, just trying to figure out what the hell was going on and like… when was I going to die? My wife watched a lot of MSNBC and they have a very intense tone and it was just incredibly overwhelming, and so I didn’t really know how to write. I was also slowing down from basically six years of constant travel and touring and finally I had a minute to myself. That was the longest I’d been in one place since 2014. About six months in, I started writing regularly again and I don’t know that I finished anything, but I at least got going on some things that I long needed to get going on.

Is there anything from that time that you want to take into your life moving forward, even if it’s just trying to be in one place for longer stretches when and if you can?

Definitely. Both my wife and I are rethinking how we live. Pre-COVID, especially in New York—we’re back and forth between New York and L.A.—we were going out all the time. I miss theater very, very much, but we want to slow down. I’m definitely still going to do speaking engagements, but I’m going to travel a lot less. At least I hope.

Are you pro or anti-Zoom?

I’m over Zoom, but I also recognize what it has made possible. When COVID started, I instantly lost most of my income overnight and that was very scary. I was like, “Okay, I can make it a year.” Which, phew, thank god. [laughs] But then six months later, people were like, “Oh we can actually do events over Zoom.” I don’t think it’s a replacement for a live event and the energy and excitement that comes with that, but I do think that it is an acceptable substitute for now. When people want you to go to a place that’s really remote, it can be a great substitute. I think it’s going to be a balance between the two moving forward.

When was the last time you went to a museum?

Recently, I was writing a piece for the Frick about the rehanging at the Met Breuer building. That was a virtual tour, but I’m actually going physically this week. The last museum before that was the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.

If the world were COVID-free, what would be a perfect art-seeing day for you? Where would you go, who would you go with, and what might you do before and after?

I would definitely go with Debbie and I would probably go to MoMA, which is one of my favorite museums. I’ve actually never been to the Whitney…

Oh!

I know, right? I’d like to go to the Whitney. New York has so many museums, so the perfect day would be to go to two museums and see some interesting and challenging art and then go to a couple galleries. We actually live in Chelsea, so you can’t spit without hitting a gallery here. I loved Sikkema Jenkins gallery when I went. And then in Los Angeles, my favorite gallery is Roberts Projects. I hope I don’t hear a horror story about them now. But recently, we saw the Jeffrey Gibson show and then the Brenna Youngblood show and those were excellent.

I’ve only heard good things about Roberts Projects, just for the record.

Oh good. Because these days you find you enjoy someone and then you find out they’re an actual serial killer.

Right. Like, “Okay, time to be done with this.”

And I’m willing to make that sacrifice for the greater good. When you think about what bad actors cost people in harm, it’s not worth it at all.

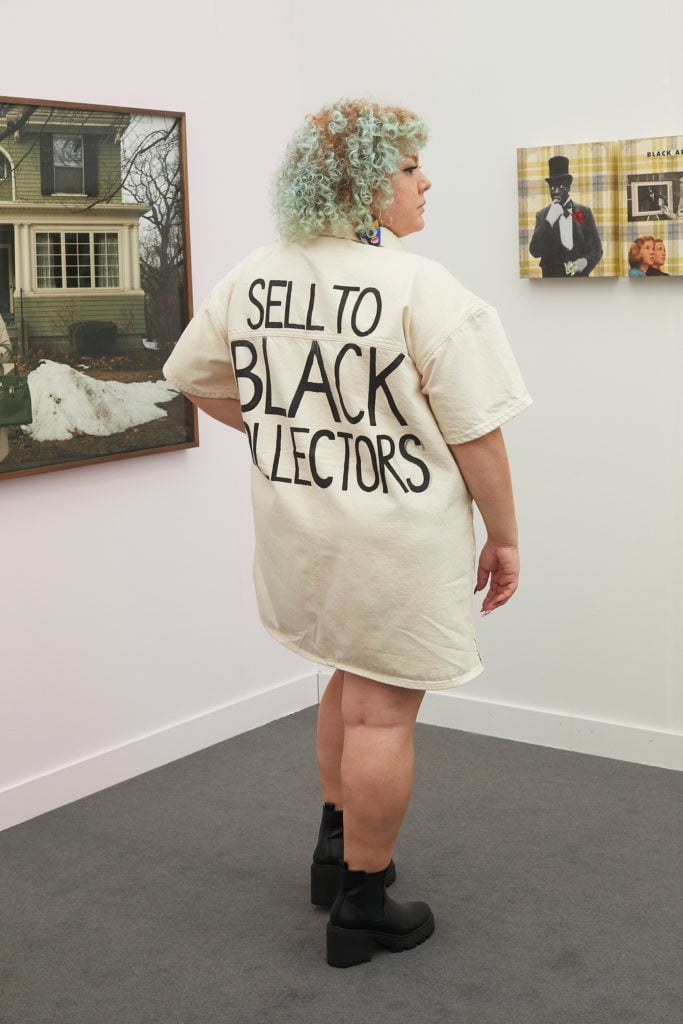

Artist Genevieve Gaignard at Frieze Los Angeles. Photo by Jennelle Fong.

Is there anything you want to end on?

I will just say I saw an image recently online that said “Sell to Black Collectors.” And I think the fact that that image needs to exist is an interesting thing and I think we need to talk more about the reluctance at times for artists to sell to Black collectors. Cause it’s like, “Wow… you’re going to block your own blessing?” It’s crazy, actually. Racism is crazy and it’s that powerful.