Art World

How Artist Duo Semiconductor Turned Subatomic Data Into a ‘Chiming Time Sculpture’ for Art Basel

For Audemars Piguet's 4th Arts Commission, the British creative duo aims to show viewers how cutting-edge science works.

For Audemars Piguet's 4th Arts Commission, the British creative duo aims to show viewers how cutting-edge science works.

Not long after finishing their new Audemars Piguet-commissioned project for Art Basel, artists Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt realized something. The British duo, who work under the name Semiconductor, had created the very same kind of device for which the Swiss company has come to be known for the last 150 years: a timepiece.

“When we visited the Audemars Piguet factory in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland, we were blown away by these chimes inside the watches that they showed us,” Jarman tells artnet News. “We’d never seen watches with these chimes inside. Then, much later on, we realized that we’d actually made a big chiming time sculpture ourselves.”

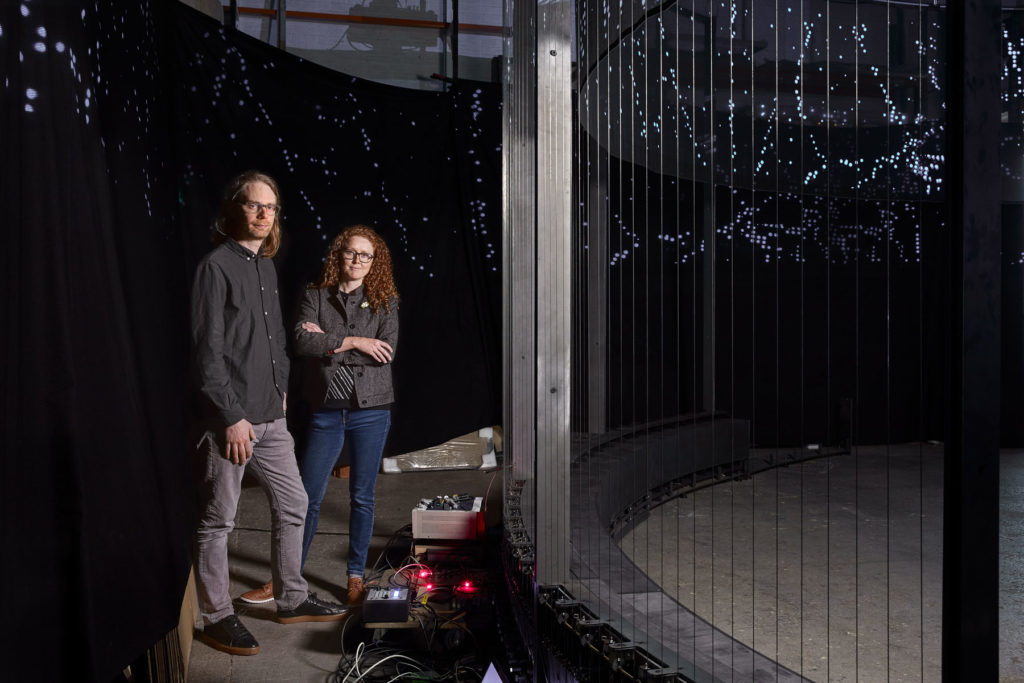

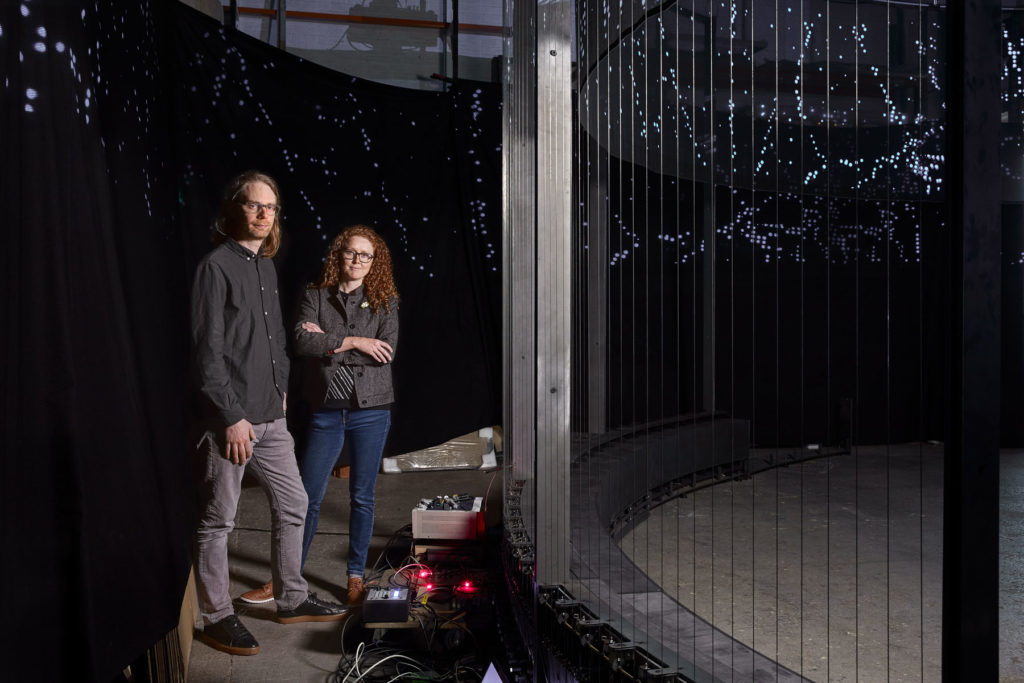

Semiconductor, HALO (2018). Installation view. Courtesy the artists and Audemars Piguet.

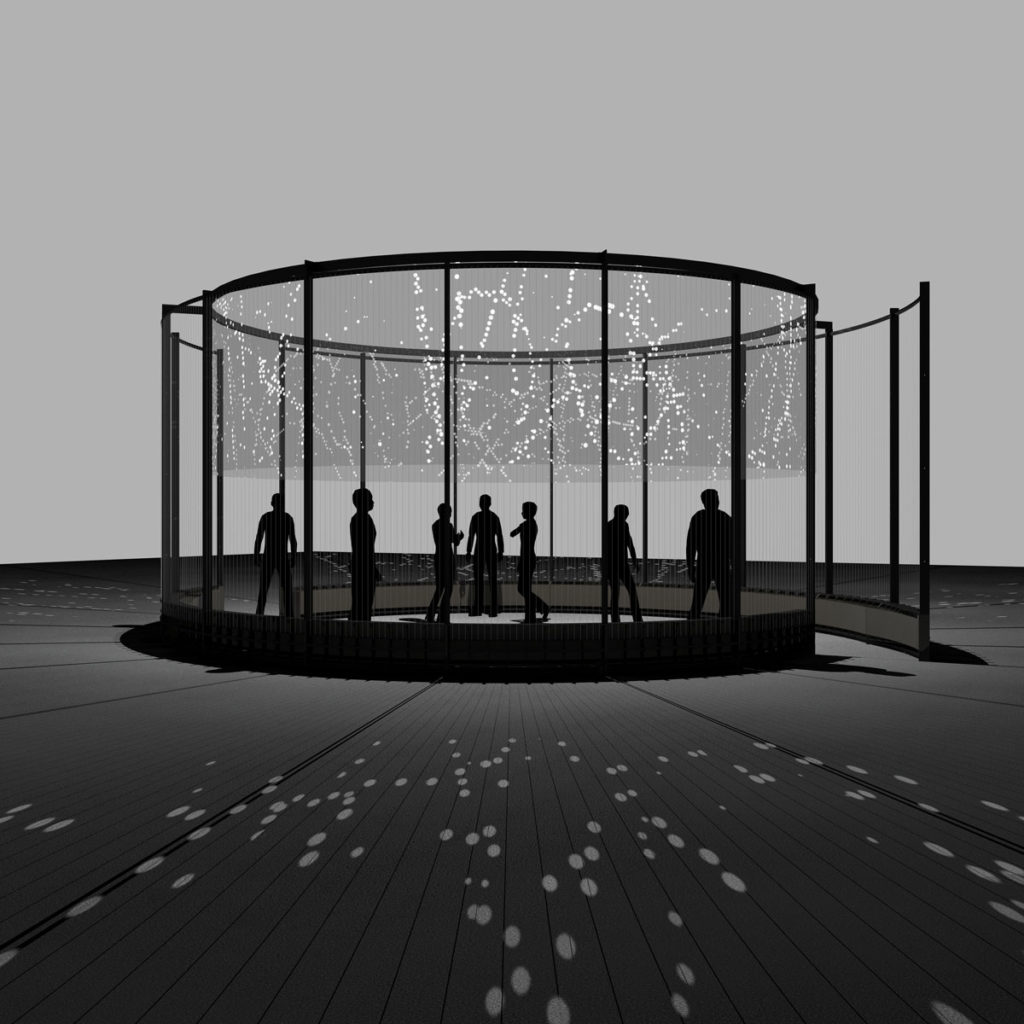

Semiconductor’s project, the 4th Arts Commission from Audemars Piguet, is a site-specific installation titled HALO. It takes the form of a 13-foot-tall, 33-foot-wide cylinder that translates subatomic data into visual and aural experiences.

On its interior walls is a 360-degree screen that displays animated graphics generated from data collected by a subatomic particle collider at CERN, one of the world’s leading laboratories for particle physics in Geneva. The outside of the cylinder is lined with 360 vertical piano strings, stretching from floor to ceiling, which are struck with small hammers—also triggered by the data. The strings aren’t tuned to a musical system; their tonality is determined by the space in which the project is installed. Thus, the sounds the installation emits—which, according to the artists, are not traditionally pleasant—are an acoustical manifestation of particles colliding.

Detail of Semiconductor’s HALO (2018). Courtesy the artists and Audemars Piguet.

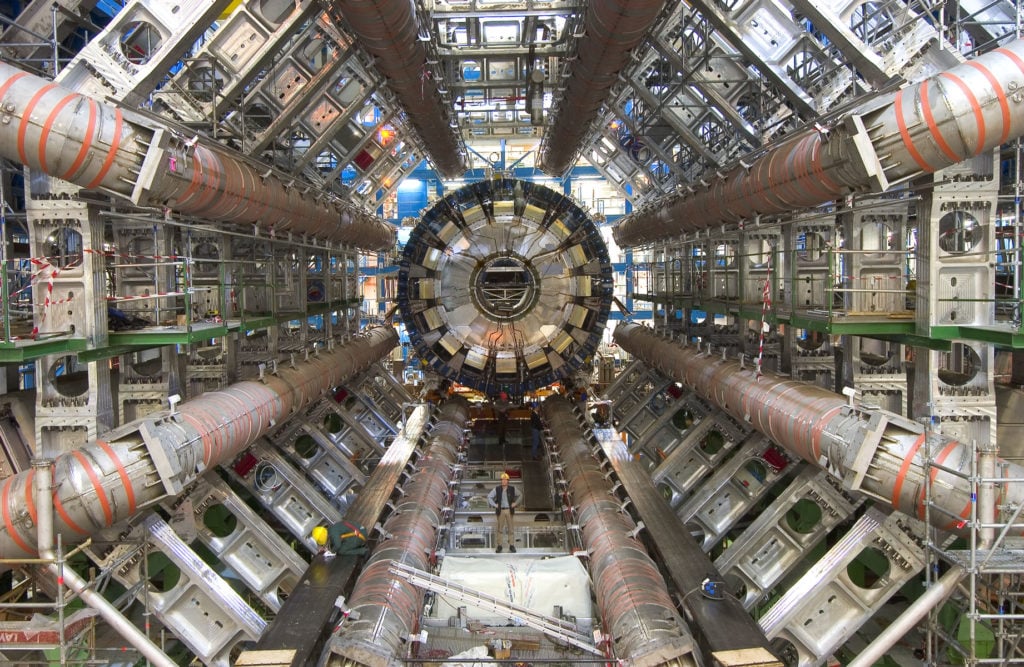

CERN is home to the Large Hadron Collider, a 16-mile-long tube of superconducting magnets that crashes protons into one another at nearly the speed of light, simulating the conditions that existed one billionth of a second after the Big Bang. The collision breaks apart the protons and produces new particles of energy, allowing scientists to study the very makeup of matter. The collider is the biggest and most powerful particle accelerator in the world.

The seeds for the project first began in 2015, when Jarman and Gerhardt participated in a residency at CERN. For two months, they spent their time conducting research, filming the campus, and simply walking around. “We poked our noses into things as much as possible,” Jarman says. “We wanted to have a first-hand experience.” She recalls a couple of occasions in which she and Joe came out of rooms to find that there was a radioactive sign on the door.

Detail of Semiconductor’s HALO (2018). Courtesy the artists and Audemars Piguet.

The artists also spent a great deal of time interviewing theoretical physicists. “Well, I say ‘interviewing’ them, but that’s not entirely accurate,” Jarman says, laughing. “It’s quite difficult to interview theoretical physicists—they’re always about a hundred steps ahead of you.”

That knowledge gap was itself of interest to the artists, though. “We’re always looking at the language of science, whether it be the tools they use or the verbal language or the way they document their data,” Jarman says. The duo sought to create a work that could be appreciated by everyone, regardless of their knowledge of particle physics.

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN. Courtesy of CERN and Audemars Piguet.

“In HALO, you don’t need to know the scientific information behind it, or even that it is scientific,” Jarman explains. “First and foremost, it’s an experience. Rather than translating the data, we want to transcend the data, so that it becomes something else.”

Mónica Bello, the head of arts at CERN who curated the project, echoes the sentiment. “The work can be appreciated because it’s very experiential,” she says. “It allows you to dive into another reality. In a way, it’s a time machine…that confronts us with the paradox of time as a social construct. And that all of us have a very different idea of what time is.”

Jarman and Gerhardt working with Mónica Bello, the head of arts at CERN. Courtesy the artists and Audemars Piguet.

For Jarman, the beauty of the project is that it harnesses both nature and science. “Looking at it, you get a sense that there’s nature in there somewhere—there’s a complexity and chaos to the data that man would not be able to create. By the same token, there’s a structure to the data and how it’s made up that has man’s signature, ” she says. “We call it the ‘technological sublime’—experiencing nature, but through the language of science and technology.”

HALO will be on view June 13–17 at the Messeplatz exhibition space in Basel.