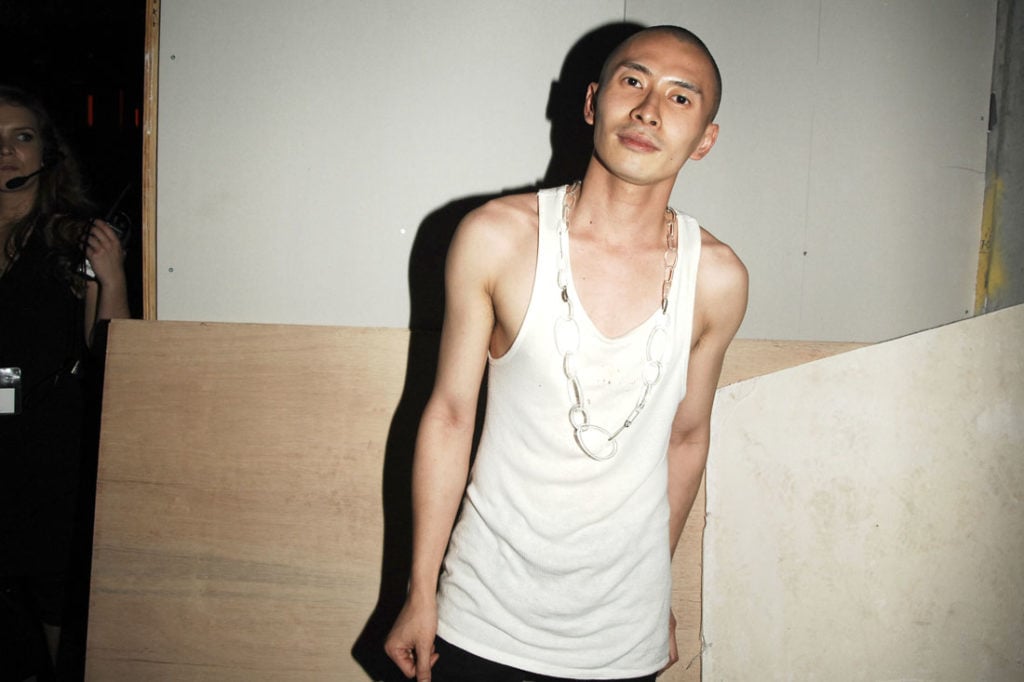

The party ended for New York’s art scene in March, when the city’s galleries, museums, and fairs—along with pretty much everything else—shut down. For Terence Koh, the artist formerly known as Asian Punk Boy and “the Naomi Campbell of the art world,” the party ended a few years earlier, when, in 2014, he “retired” from art and moved to a mountaintop in the Catskills. Koh gave up his cell phone, his performances with Lady Gaga, and his days getting “drunk and drugged” in Miami—and now he has some words of wisdom for former colleagues who may be struggling with isolation and lost opportunities.

“Living in the Catskills prepared me more than most people because I’m able to say, ‘OK, this is the situation and this is what life has brought you now,'” the artist tells Artnet News. “Life is always changing and always unpredictable.”

Even though the lockdown era has disrupted our daily routines, familiar traps will reappear, he says. “Being stuck at home you have just as many channels of escape as going out. The medium of escape is the same whether we go to a bar and flirt with somebody or go to the Whitney,” Koh says. “At home, when you’re about to check Instagram, try to slow down time itself and ask, Why do you want to check Instagram? Is it because you see future images of a heart, the image of love itself? An endorphin hit?”

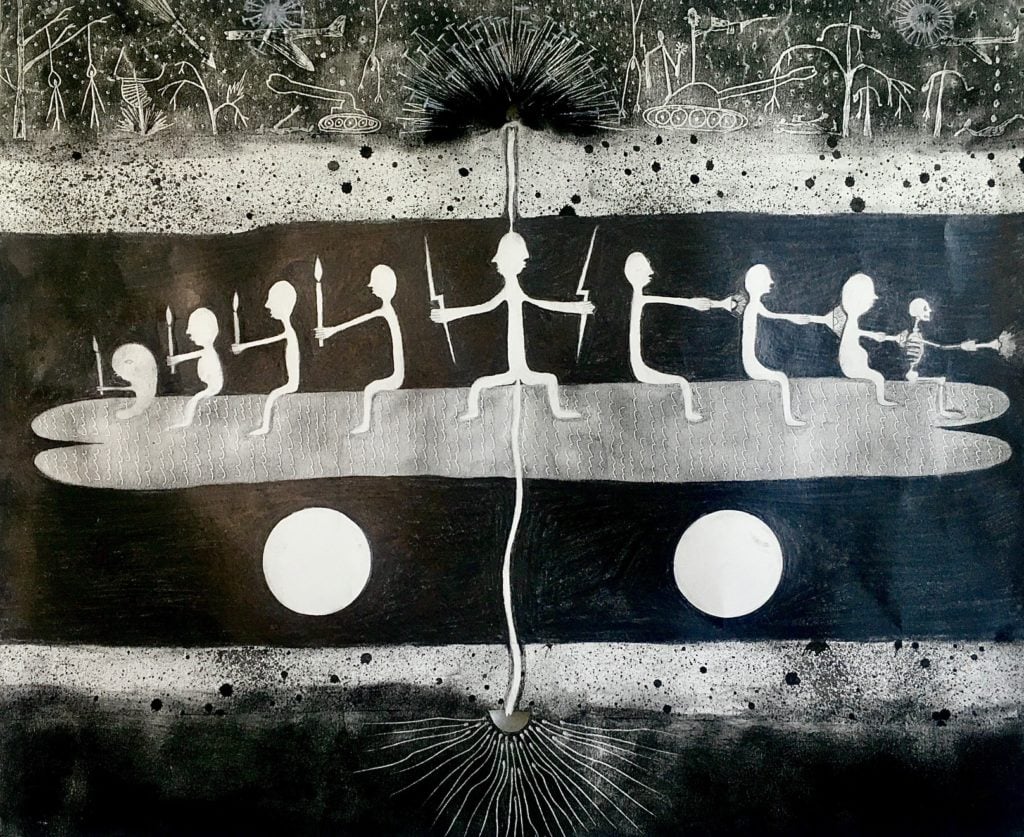

Koh has periodically resurfaced in the years since his “retirement,” though in more restrained form. He reconstructed a “bee chapel,” as well as sculptures derived from its wax, at Andrew Edlin Gallery in New York in 2016; two years later, he poured dirt on the floor of Brussels’s Office Baroque gallery and lit a fire pit on top. He was set to open another show at Edlin’s gallery last month, but it was translated into a virtual exhibition instead (through June 24).

Terence Koh, Untitled (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

“I went through despair at first when my physical show was cancelled,” Koh says. But in adapting to the online version, he discovered new modes of expression that felt just as vital as the drawing show he had originally planned. While those drawings are on view in the digital show, so are pages from Koh’s daily quarantine diary, recipes from his artist friends—including Marina Abramovic’s “recipe” for water—and an online store for bartering goods such as cassette tapes and a cannabis plant.

Ultimately, he decided, the virtual exhibition is just as good as the live one would have been. “Do we even need art galleries anymore?” Koh wonders. “Everything I want to do as an artist I’m able to do across all mediums, whether on Instagram or an online exhibition or a sculpture or a performance on Zoom or in a museum. I believe that the fundamental point of an artist, which is also the fundamental point of every human, is to open up all the possibilities for existence.”

And now Koh himself is experimenting with another possible existence—in Los Angeles, where the artist moved two years ago with his boyfriend, who had started to feel a little too alone in the Catskills. They’ve brought with them many of the habits they took up in the mountains—beekeeping, composting, gardening, and making pigments out of marigolds and daffodils.

Simon Haiku and Terence Koh during the second meeting of the Sunrise on Sunset Club, a group they started on the street with signs and chairs to discuss race and anything else. Courtesy of Terence Koh.

“A human being, I’ve discovered, is not meant to be alone so much, just like the honey bees who touch each other 3,000 times a day—their legs and antennas rubbing in all this nonverbal communication. It’s interesting what happens to a human without these senses,” Koh says.

“We all need this alone time, but what the Catskills taught me is that we’re capable of taking a breath anytime, anywhere, even in a dance club at 2 a.m. drunk—at any time, any human is able to take a breath and go back to this timeless moment,” Koh says. “It’s this return to a timeless moment that is the highest purpose of us as humans.” Which may come as good news for those who feel time moving very, very slowly these days indeed.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.