Artist Benjamin Hannavy Cousen (b. 1977), who studied at the University of Leeds, near where he lives, has a practice centered on transforming literature into visual art. Developing a unique “color register” for each book he focuses on, his works are effectively a visual translation. An author himself, Hannavy Cousen has written widely about art, history, and visual culture, lending another facet to his artistic practice. Employing a distinctive and proprietary method of applying paint via a syringe, the artist not only tackles the boundary between visual art and literature but also between painting and sculpture, offering a textural, tactile element to his works.

We reached out to Hannavy Cousen to learn more about his inspirations, how he creates his work, and his future plans.

Benjamin Hannavy Cousen in his studio. Courtesy of the artist.

Tell us about your journey as an artist. Where did you start?

Art has always been an integral part of life. It was part of my childhood. My parents met at art school and my father is a painter. I always felt like it was what I would like to do, however, for complex reasons, I pursued an academic life until I realized what I really wanted was to make meaningful things through art. I needed to take a leap of faith. It became easier when I landed upon the language of paint I now use. This emerged from studying literature and art history; I was interested in these two languages and wanted to combine them into a new manner of expression.

Can you talk about how you make your work from a technical perspective?

I construct most of my work using a syringe and needle, and I have begun to see them more as constructions than paintings. I needed a way of layering color so that each line retains its integrity and is “readable,” almost archaeologically, despite being overlayed and buried. I construct paintings that make physical the process of reading. One cannot unread something, there is an accumulation within memory. Often my paintings have a huge agglomeration of paint, which is like this acquisition of “read” text. These works become about memory itself—the use of literature is a tool to attempt to express something universal.

These works are simply paint on a flat surface. The three-dimensional shapes are from layering the paint, they emerge through physics rather than design.

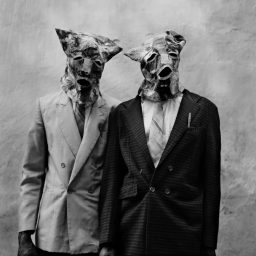

Benjamin Hannavy Cousen, detail of The Sea, The Sea (History) (2020). Courtesy of Merville Galleries.

Literature plays a central role in your work, with your pieces being titled after novels. How do you choose which books to focus on? How do they figure into each work beyond the title?

Books play an integral part. The colors that appear in each painting are the colors that appear in the text. If there is “red” in the book before a “blue,” then “red” will appear in the painting before “blue.” I have developed a “color unconscious.” Every text has this unique unconscious. It’s my job to bring this out and make it into an object. These authors have in some way unwittingly created these paintings, and I am collaborating with them.

There is often a nod to the subject matter of the book. For example, the painting of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea (2020) has a disturbing serpentine form meant to echo the sea monster that haunts the story.

As for choosing the books, I find it is best to read without preconceptions of what will make a painting. It is always obvious what will work.

What do you want the viewer’s experience of your work to be like?

I hope there is some sense of joy. It is important that my paintings are accessible as objects without having to know all the theory that goes into them. I realize this makes them seem like aesthetic objects, but I like that they can be both aesthetic and carry meaning. If I wanted them to be purely aesthetic, I would stop partway through the construction when they “look” best.

I hope they [lead] to a new way of looking at texts, painting, and memory. I’d like viewers to take away this sense that there are undercurrents in everything, that things are both not what they seem and what we make of them.

Benjamin Hannavy Cousen, Storm of Steel (2019). Courtesy of Merville Galleries.

What artists—or authors even—have influenced your work the most?

I try to be open to influence from anywhere it might spring. I’ve recently been experimenting with Instagram and there is some interesting stuff on there. But I can come up with a classic list: Bridget Riley, Ali Smith, Virginia Woolf, W. G. Sebald, J. M. W Turner, Gerhard Richter, Bob Dylan, Nick Cave, PJ Harvey, Werner Herzog, Søren Kierkegaard, Gilles Deleuze, and D. Ferrett.

Last year, you had a show “Rings of Saturn and Other Objects” at Merville Galleries. Tell us about it.

It was named after W. G. Sebald’s book The Rings of Saturn (1995)—although I have not braved trying to paint Sebald yet. In the main room, we created a Rothkoesque meditative chapel-type feeling. But there was a contradiction because many paintings were quite dystopian: Chernobyl Prayer (2020), The First Circle (2020), 1984 (2017). It’s interesting how many Russian texts I do—I like that I am making translations of books, and these are translations of translations (Walter Benjamin would call this a continual process of refinement). There were also sci-fi paintings about Isaac Asimov, Ted Chiang, and M. John Harrison, as well as more playful pieces such as Alice in Wonderland.

Benjamin Hannavy Cousen, The Penguin Book of English Short Stories (2017). Courtesy of Merville Galleries.

Looking towards the New Year, do you have any new projects planned? Or any new ideas that you’d like to engage with?

There are a lot of plans. In October, I was a guest artist at the Sculpture Gallery in Leeds, and Boys in Zinc (2022) is on display there now. I’m interested in this nexus between painting and sculpture, and I have ideas for making sculptures that become paintings. I am also going to make a different series that may not be so closely associated with literature.

I’ve been working with Merville Galleries for seven years, which has been fantastic, but they’re no longer doing art fairs and shows. With their support, I’m seeking new representation and look forward to the opportunities and challenges that will bring.

Learn more about Benjamin Hannavy Cousen and his work here.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.