Art & Exhibitions

Andy Warhol Died 29 Years Ago Today, Here’s a Look at One of His First Silkscreens

THE DAILY PIC: From his very first silkscreens, Warhol was a kind of Old Master.

THE DAILY PIC: From his very first silkscreens, Warhol was a kind of Old Master.

by

Blake Gopnik

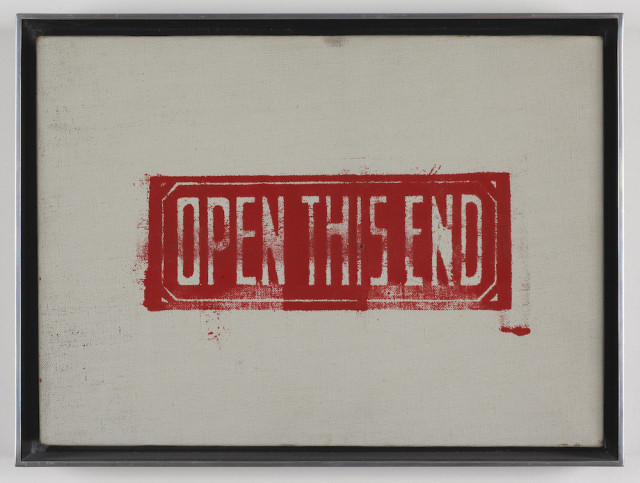

THE DAILY PIC (#1495): Andy Warhol died 29 years ago today in a hospital in New York, after a routine gallbladder operation. It seems only fitting to commemorate the end of his artmaking by revisiting its beginnings. The work I’ve chosen as today’s Daily Pic was made in the spring of 1962, as one of the very first of the silkscreened canvases that became Warhol’s signature mode for the next quarter century. It’s the titular work in a touring exhibition called “Open This End: Contemporary Art from the Collection of Blake Byrne,” curated by the art historian Joseph Wolin and now at the Wallach Art Gallery of Columbia University.

From the moment Warhol’s silkscreens started to appear, observers compared them to the readymade sculptures that Dada artist Marcel Duchamp had come up with 50 years earlier: A real store-bought urinal, for instance, transformed into a work of art simply by virtue of Duchamp’s declaration that it should be displayed as one. Before they were ever called Pop Art, Warhol’s pieces were labelled neo-Dada. But I think that’s always been a misreading of Warhol’s art.

For one thing, the shipping label depicted in Open This End is nothing like a readymade, because its prototype doesn’t seem to have actually existed. Like other works in the same series (This Side Up, for instance, or Fragile: Handle With Care) Warhol’s silkscreen was based on a carefully measured, hand-made drawing that simply simulated the kind of printed, mass-produced label he might have come across in the course of sending and receiving packages. That means that Open This End is really a fairly traditional work, right in the thick of the still-life tradition of the Old Masters: It uses artistic representation, even invention, to draw our attention to some feature in the world that we might otherwise neglect. Like most works of art in the Western canon, that is, it’s built around the principle of ostension – a desire, first and foremost, to point at, and point out, the things all around us. That’s what makes it so very different from the Duchampian readymade, which is above all an absurdist gesture that talks about the nature of art and the art world, and hardly at all about the particular objects that Duchamp chose to present as art. It’s not hard to imagine that a porcelain toilet bowl would have done almost as good a job playing at sculpture as Duchamp’s urinal did. (Almost, I said: I recognize that there are special issues of gender and class involved in his choice of a urinal, and its shape also made it evoke the echt-artistic sculptural niches of the Renaissance. But those are clearly secondary concerns for Duchamp.)

Whereas, with almost every image Warhol ever made, the subject pointed to in his ostension is crucial to the meaning of the art. In the case of Open This End, there’s a very deliberate substitution of the work of art you expect to see on the gallery wall – a portrait or still-life or even abstraction – with the packaging it would normally come wrapped in. That substitution suggests (at last echoing Duchamp) that the institutions and procedures of the art world, and even its standard wrapping materials, are as worthy of our attention as any fine-art pictures those institutions and procedures are normally in aid of.

I wonder if the meaning of Open This End doesn’t also depend on the added fact – almost an insider’s joke – that Warhol himself had barely been involved in any of the art world’s institutions and procedures: For more than a decade his own art production, such as it was, had consisted of a stream of works on paper and commercial illustrations that hardly needed to be shipped with the care instructions of fine art. Some of his first care-worthy objects thus consist of the declaration that they are worthy of care.

One final thought: I can’t help feeling that the phrase Open This End comes with faintly salacious overtones about which end an artist is supposed to be open at, or not. (The Blake Byrne collection on view at Columbia is full of such overtones, which may have got me thinking along these lines.) In the 1950s, Warhol’s fine art had been built around pioneering homosexual content that had won him precisely zero attention or respect. His career only took off once he replaced sex as his subject with other kinds of American consumption.

Luckily, the sublimation only had to last a little while: Within two years of hinting that we should Open This End, Warhol gave us a Blow Job. (The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, partial and promised gift of Blake Byrne; © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.

See more Warhol works at artnet Auctions’ latest Pop Art sale.