Art & Exhibitions

Anri Sala at the New Museum: Our Engineered Answer to Picasso

THE DAILY PIC: The Albanian shows how far we've come from our modern roots.

THE DAILY PIC: The Albanian shows how far we've come from our modern roots.

THE DAILY PIC (#1483): Yesterday, the New Museum in New York opened a major solo show of Anri Sala, an Albanian-born artist who now lives in Berlin. The exhibition is fabulous, and proves Sala is the worthy heir of the very greatest 20th-century artists – Kandinsky, Picasso, Bourgeois and all the other giants of modern art who underlie every one of our 21st-century efforts.

Today’s Pic is a still from a projected video called Long Sorrow that is every bit as complex and compelling as anything by Sala’s illustrious predecessors. His video shows the great free-jazz improviser Jemeel Moondoc playing his sax while perched dangerously high on the façade of a Modernist apartment building in Berlin. In the video’s New Museum presentation, another saxophonist, André Vida, walks into the gallery every once in a while and responds, live, with his own improvised riff on what he hears and sees his colleague playing in the projection. It feels as though we’re trapped inside a peculiar game of infinite regress – caught between two mirrors that happen also to be warped.

But here’s what makes this piece notable, even by the standards of Sala’s great antecedents: He is engaging with all the classic devices of modern and contemporary art (improvisation, intuition, expression, disorientation, the ephemeral) but his piece come at those devices from a great distance – not so much engaging with them, really, as simply representing them. That is, the actual high-tech means that Sala uses aren’t “artistic” at all; they are the standard video and audio tools of Hollywood and Madison Avenue. They are trained on those earlier Modernist devices but they aren’t of a piece with them. The classically modern idea that form should mirror content breaks down in Sala’s art: Nothing could be less like a wild jazz improvisation than a highly engineered depiction of it, complete with crane shots.

So even as we enjoy the feel of Modernist innovation in Sala’s musical subjects – it’s there in the building he shows us as well – we have to recognize this innovation’s past-ness, and that it belongs to a world we can only look at and digest as an image, at several removes from where we are today. The musical radicalism of Moondoc and Vida is of a piece with the building that Moondoc is hanging from – both building and music are now subjects of nostalgia and antiquarianism rather than of live engagement with ideas that are fully current. It so happens that I love the kind of music those jazzmen are playing, but I love it the same way I love Mozart and Bach.

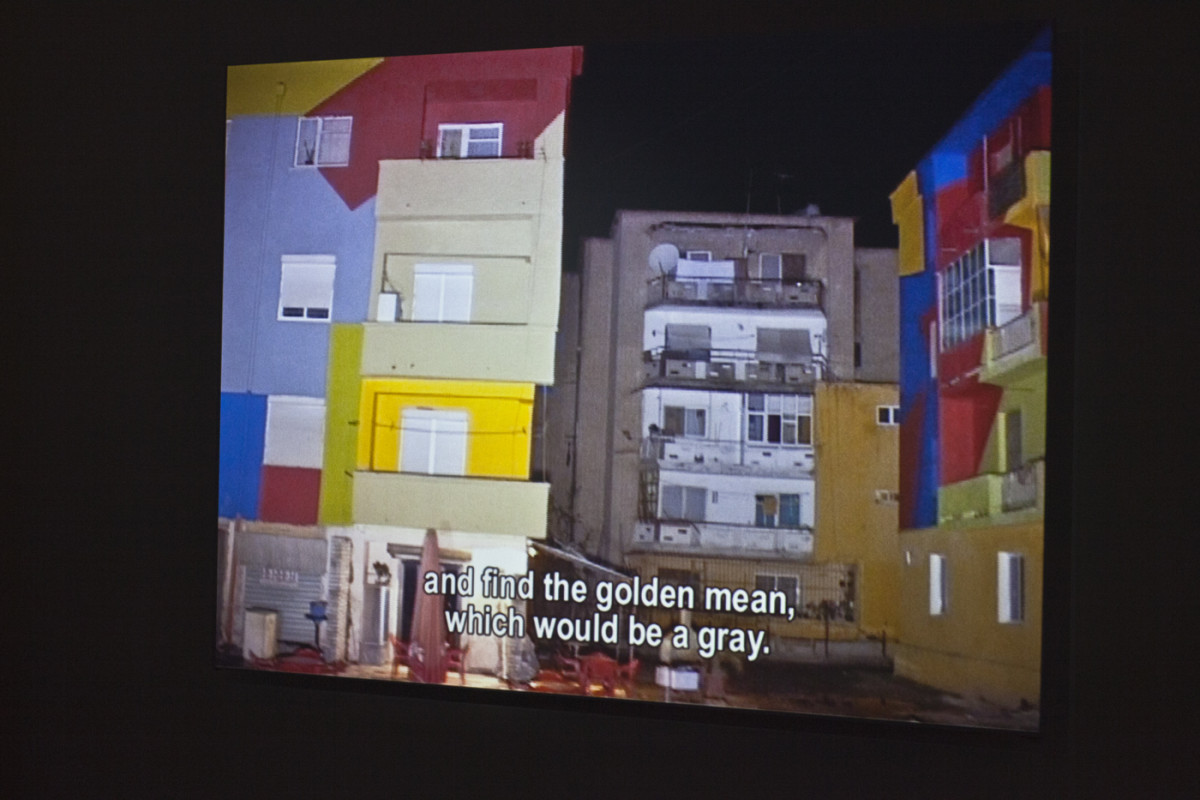

The same issues are at play in many of the New Museum’s other Salas – in a wonderful documentary video about an attempt to enliven the city of Tirana by painting its buildings in Color Field patterns, as well as in amazing installations riffing on the music of Ravel and Schoenberg. (I wrote at length about the Ravel piece in 2013, when it was in Venice.) We can’t truly inhabit the once-radical art that these works are about. We can only re-present it for cool and calm recollection.

What’s strange is that Sala does such a great job manipulating our recollection that it feels as though he’s creating a new cutting-edge, even as he seems to show that one can no longer exist. (Photos by Lucy Hogg)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.