Art & Exhibitions

In Times Square: Warhol, Dylan, Harry Smith—and Scholar Tom Crow

THE DAILY PIC: Warhol's Screen Tests, and Crow's take on Pop art

THE DAILY PIC: Warhol's Screen Tests, and Crow's take on Pop art

Thanks to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and Times Square Arts, tomorrow, and every night for the month of May, the video billboards in Times Square will be filled with ten of Andy Warhol’s great Screen Tests—his three-minute filmed portraits that are as profound as any Rembrandt. (But they only screen from 11:57 to midnight; consumerism cannot spare more than a few minutes daily for art; Warhol would have understood. At least the Screen Tests won’t be made to loop, which is always a travesty of their original fleetingness.)

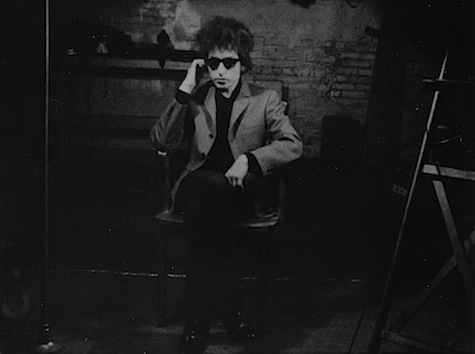

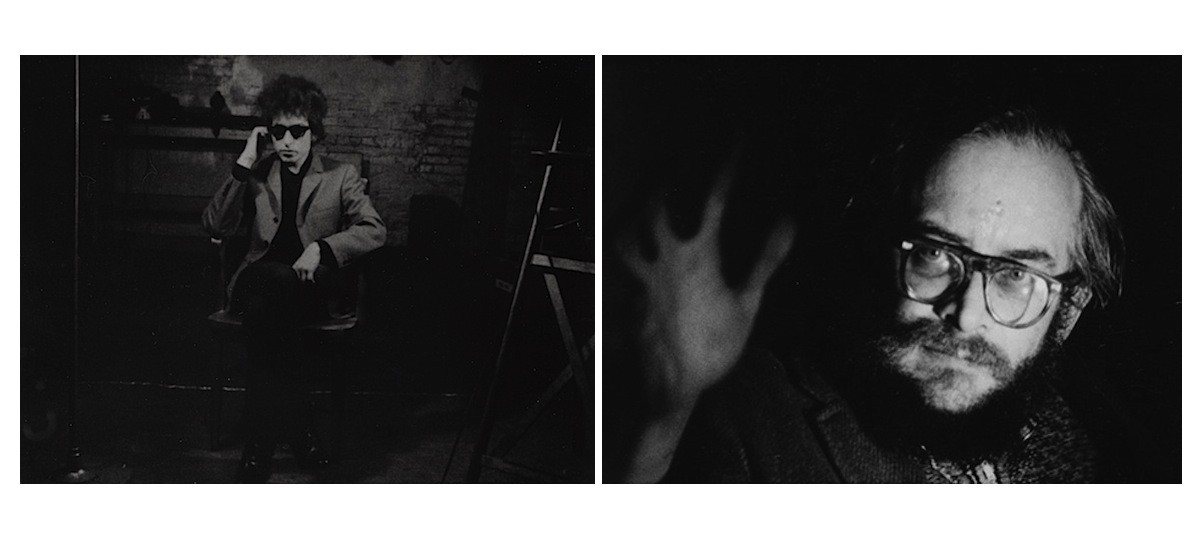

For today’s Daily Pic, I’ve chosen stills from Warhol’s moving portraits of Bob Dylan and Harry Smith, because those two are central protagonists in an important new book called The Long March of Pop, by the scholar Thomas Crow.

Crow argues that a conflicted, vibrant relationship to folk art and folk music is central to understanding the great American Pop art of the 1960s (including Warhol’s), as well as the most important popular music of that era (especially Dylan’s). He traces the absurdly complex interactions between folk, fine and popular art forms across the first half of the 20th century – a story in which a central part is played by Harry Smith, an experimental filmmaker (like Warhol) whose records spread word of America’s greatest folk traditions (especially to Dylan). There’s no space here for me to go into greater depth than that on Crow’s achievement, but I will add a kind of footnote to it.

What Crow didn’t know or note when he wrote his book—because no one had researched it—was that the Pittsburgh where Warhol grew up and got his education was a hotbed of folk art. Crow does point out that the art world’s interest in outsiders got its start at the 1927 Carnegie International exhibition in Pittsburgh, which included a headline-grabbing work by the local laborer John Kane. What counts as new news is the fact that the Carnegie’s art museum continued to show untrained artists—including Horace Pippin, Grandma Moses and Henri Rousseau (who got a major solo)—long after other influential institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art, had lost their original interest. This puts Warhol much deeper, and more self-consciously, into the debate of folk versus modern than Crow could have realized: You could say that his path from folk- (and mom-) inspired illustration, in the 1950s, to sleekly modern fine art, in the 1960s, is all about this debate. (And a final footnote to my footnote: The program at Pittsburgh’s Outlines gallery, only now being recognized as one of the great modern-art venues of the 1940s—and as a crucial Warhol influence—once presented a concert by the major folk musician and scholar John Jacob Niles, further proving the importance of the folk/modern nexus that Crow has unearthed elsewhere.) Image ©2015 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved.

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.