Art & Exhibitions

Whitney Museum Hangs Jackson Pollock Painting the Wrong Way

The Pollock catalogue raisonné tells a different story.

The Pollock catalogue raisonné tells a different story.

A Jackson Pollock canvas is hung in an unconventional way in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s inaugural exhibition, “America is Hard to See.”

In a handbook of the collection, Pollock’s 1950 drip painting Number 27, 1950 is shown horizontally, as it is in the Pollock catalogue raisonée.

But at the Whitney today, it’s displayed vertically.

It’s signed in a way that would suggest it was meant to hang horizontally, such that the signature reads top to bottom as the painting currently hangs.

The curators’ unconventional installation is intentional, says a museum spokesperson, and is based on photographs showing that Pollock hung it that way in a 1950 exhibition at New York’s Betty Parsons Gallery.

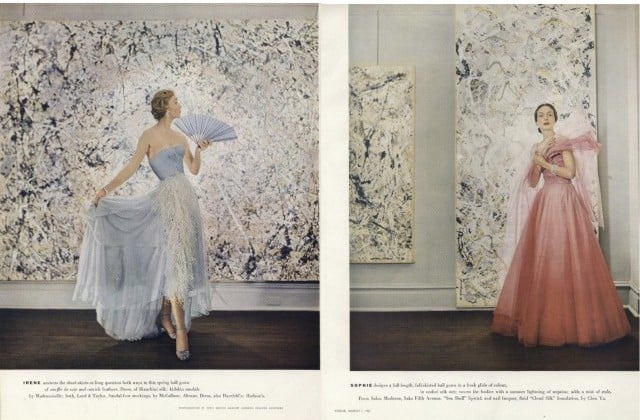

A 1951 Vogue spread shot by Cecil Beaton shows Pollock’s painting Number 27, 1950 (right), hanging vertically at Betty Parsons Gallery.

“It was a revelation,” then-Whitney curator Lisa Phillips told the New York Times in 1999, when she saw a lecture by art historian T.J. Clark with an image of the painting hanging vertically. She’s now the head of New York’s New Museum.

Installation view of Jackson Pollock’s Number 27, 1950 (1950).

Photo: via artnet News.

“I’ve heard that the vertical hang at Betty Parsons was due to space limitations, but I haven’t seen any documentation to support that,” said Dana Miller, curator of the museum’s collection, in a phone interview today. “Space was perhaps a factor, but if Pollock had objected to it being hung vertically, it wouldn’t have happened. Also, it was hung that way after the signature was applied. Had the signature not been on the painting in the Betty Parsons show, I don’t think we would have done what we did. But because it’s signed in the Betty Parsons show and it’s hung vertically, it became an option we were comfortable with.”

Miller also points out that the vertical hang is the only one that was ever photographed, as far as she knows.

“The only photographic documentation we have access to prior to the Whitney’s acquisition of the painting shows the painting in its vertical hang, in the Betty Parsons show,” she said. “The Whitney bought it in 1953, shortly after it was made. It’s not as though there was a long exhibition history.”

The Whitney has hung it this way before, too, in its 1999 show “The American Century: Art and Culture 1900-2000.” At the time, longtime Museum of Modern Art curator Kirk Varnedoe told the Times that had Pollock not wanted the painting to hang vertically, Parsons never would have displayed it that way.

“I’m not gonna lie, it’s not a no-brainer, and we discussed it at length,” Miller said. “We initially planned to install it horizontally, but we felt it had a greater sense of scale when you turn it vertically. We live in a city that has some of the most amazing horizontal Pollocks. But this one is just 106 inches wide [just under 9 feet], and at that relatively diminutive scale it doesn’t have that same sense of immersiveness. For the purposes of this show we felt that the work held its own and had a greater sense of scale when hung vertically.”

Miller cautions against reading too much into the vertical hang.

“This is not definitive,” she said, and pointed out that in future installations, “It will be hung horizontally, and it will be hung vertically.”