Leonardo da Vinci lovers hoping that the Louvre’s blockbuster anniversary exhibition will settle questions concerning the whereabouts of the missing $450 million painting, Salvator Mundi, will have to keep holding their breath. With just three days to go until the exhibition’s public opening, the question of whether the prized painting will be present or absent still hangs in the balance.

The largest-ever exhibition of Leonardo’s work is set to open at the Louvre this week, on October 24. The show, which has been 10 years in the making, marks 500 years since the death of the Renaissance master. Its two curators, Vincent Delieuvin, from the Louvre’s department of paintings, and Louis Frank, from the department of prints and drawings, have exhaustively re-examined the existing bibliography of Leonardo’s life, and have made new headway into the master’s life and work.

While the Louvre already owns five paintings and 22 drawings by Leonardo, it will also show nearly 120 paintings, sculptures, drawings, manuscripts, and objets d’art on loan from some of the world’s most prestigious art institutions, including the Vatican Museums and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In all, the exhibition features some 160 works, including at least nine paintings and 80 drawings by Leonardo, as well as works by his two main disciples, Marco d’Oggiono and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.

The Salvator Mundi

Whether the most expensive painting in the world, which is believed to be owned by the Saudi crown prince Mohammad bin Salman, makes an appearance in the show will be as much a “surprise” to the curators as it will be to visitors, Delieuvin says. Salvator Mundi has been conspicuously absent from public view since it sold at auction at the end of 2017 for $450 million.

“If the painting is there, it is because the lender has decided to lend it. If it is not there, it’s because the lender decided not to,” Delieuvin says. “We still don’t know if it is coming, the lender hasn’t given the final say yet.”

Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi is seen at the Christie’s in New York in 2017. Photo by Mohammed Elshamy/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

The validity of the work’s attribution to Leonardo has been subject to contention among art historians, but the French curators cannot weigh in on debates over privately owned works because they are functionaries for the state. An attribution from the Louvre will only be given if the painting is loaned for the exhibition.

The show certainly does not depend on the inclusion of this particular work, however. “The way the exhibition is constructed, it is not conditioned on the presence or absence of any painting,” Delieuvin says. Because of Leonardo’s profound interest in science and technology, the curators decided to include in the show all the infrared reflectograms that show deeper layers of paint, and sometimes hidden images, on the artist’s canvases.

These will in some cases be shown side-by-side with their companion paintings, and in others will stand in for works that are absent, such as the Annunciation from the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, the National Gallery of Washington’s portrait Ginevra de’ Benci, the Madonna of the Carnation from Munich’s Alte Pinakothek. The Lady with an Ermine will also not be on loan from the National Museum in Krakow, Poland.

Vincent Delieuvin poses next to the Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum. Photo by Eric Feferberg/AFP via Getty Images.

The Mona Lisa will remain on view in its permanent hanging space, in the museum’s grand Salle des États, rather than move to be with the rest of the show in the Napoleon Hall. Delieuvin explains that this is purely for practical reasons: The majority of the 30,000 visitors who come to the Louvre every day want to see Mona Lisa, and the Napoleon Hall can only accommodate a maximum of 7,000 people. “If we put the Mona Lisa down there, the exhibition would be practically unvisitable,” he says.

Leonardo’s most famous painting will also figure into a new virtual-reality experience at the end of the exhibition. “This will allow people to rediscover the Mona Lisa, and I think that it will give people the desire to go upstairs and see the painting in her room, which has just been renovated with a new intense and deep dark blue color,” Delieuvin says.

Political Interference

A bitter political standoff between officials in France and Italy over international loans briefly threw a wrench into the exhibition, as Italy’s former nationalist culture ministry tried to renege on loans previously promised to France, with one official complaining that “Leonardo was Italian, he only died in France.”

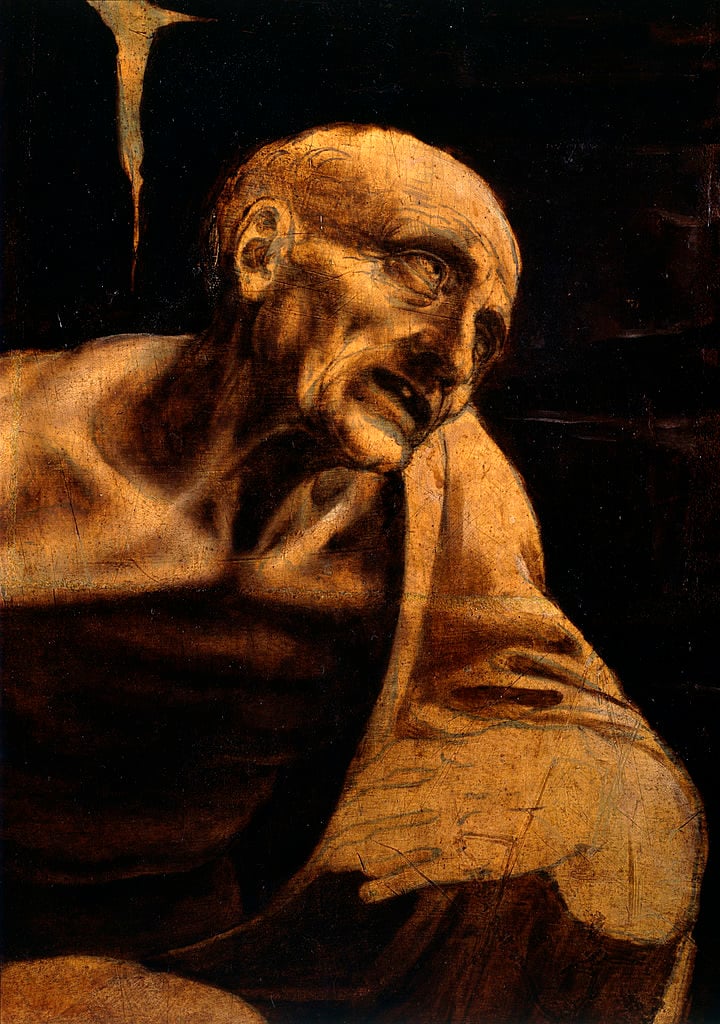

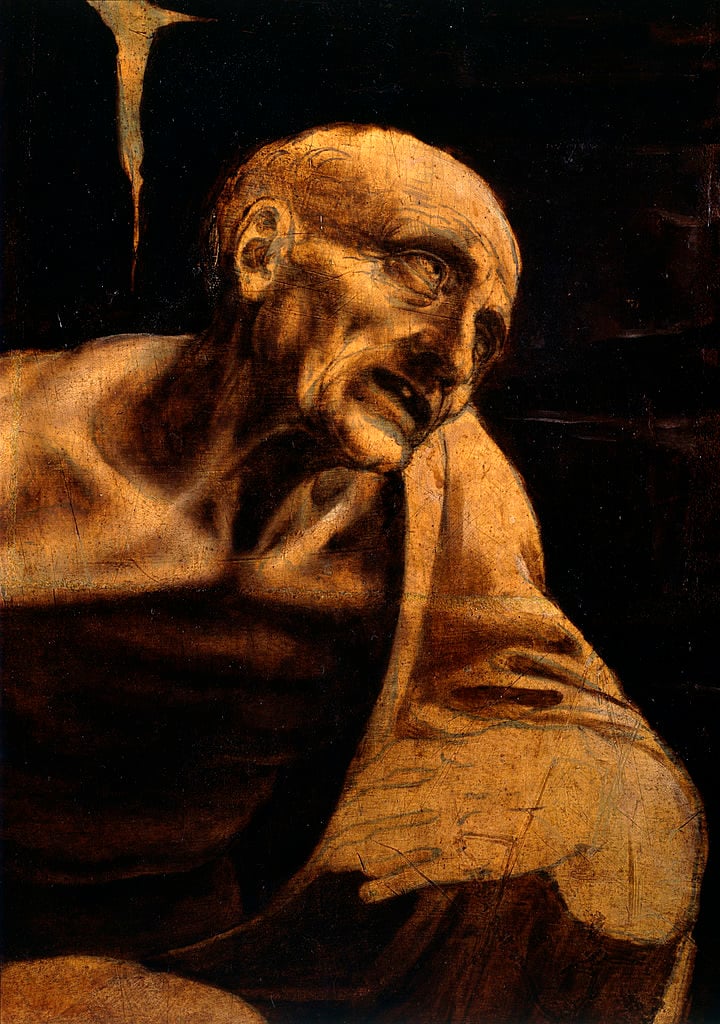

A detail of Saint Jerome in the Wilderness at the Vatican Museums. Photo by Electa/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images.

However, important loans were eventually secured, including Leonardo’s iconic Vitruvian Man, after an eleventh-hour court ruling threw out a case mounted by an Italian heritage conservation group that tried to block it from leaving the country. Other “extraordinary works” loaned from Italy include the Vatican Museums’s Saint Jerome in the Wilderness.

But it was not just the Leonardos in the exhibition that were hard won. The exhibition begins with a sculpture by Andrea del Verrocchio, under whom Leonardo apprenticed during his youth in Florence. Verrocchio’s Christ and Saint Thomas, owned by Florence’s Orsanmichele, that was offered in exchange for 16 reciprocal loans, including two Leonardos.

Asked whether national politics often interferes with curatorial work, curator Louis Frank says that it comes up primarily when a subject captures public opinion as much as Leonardo does. “But it is worth noting that, in the majority of cases where a loan was refused, it was not for political reasons,” Frank says, adding that most of the loans were negotiated between museums, not heads of state.

Overall the curators say they are “very happy” with what they have managed to secure for the exhibition, and expressed particular thanks to the generosity of the Queen of England, who has loaned some 24 drawings from the Royal Collection. Despite the ongoing Brexit discussions, the UK was the biggest lender of works to the exhibition, sending works from the British Museum, London’s National Gallery, the Courtauld, and the National Galleries of Scotland, among others.

New Revelations

The exhibition is the outcome of 10 years of curatorial research. “When we began our work we didn’t understand anything about Leonardo, because the bibliography is immense and, above all, it is contradictory,” Frank says. “We had to start all over again to understand.”

Delieuvin undertook the enormous task of reading the entire bibliography concerning Leonardo and, together, the curators re-examined all the available historic documents and literary sources relating to the artist. They redid transcriptions and translations, and carried out new laboratory analyses. The Louvre’s own works have undergone new technical analyses, and three—Saint Anne, La Belle Ferronière, and Saint John the Baptist—have had fresh conservation treatments.

“All this means that we now have an image that is not totally different, of course, from the Leonardo we know, but it is now built on foundations that are clean and solid, and there are many details that we have clarified,” Frank says.

A visitor looks at the painting The Virgin of the Rocks at the Louvre. Photo by Jacques Demarthon/AFP/Getty Images.

Their research has, for example, offered up a better understanding of the history of the two versions of the Virgin of the Rocks. Until now it was believed that there was a years-long conflict over the earlier painting, which is part of the collection at the Louvre, after it was rejected by the Brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception for being heretical because of its depiction of an angel figure. “Today we understand that this was a false idea, and there are many of this kind of false ideas in the historiography of Leonardo,” Frank says.

The case was solved with the use of infrared reflectography, which shows that the angel figure was actually a later addition to the first painting, indicating that the conflict was instead a financial one resulting from the brotherhood not wanting to pay the supplement that the painters wanted.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne Inv. 776 © RMN, musée du Louvre / René Gabriel Ojéda.

A further example of the curators’ break from traditional beliefs about Leonardo’s work concerns the Mona Lisa and Saint Anne, which were long thought to be late works, dated at around 1510. A document discovered in 2005, however, which has been a source of contention among art historians, shows that both works were actually in advanced stages as early as 1503. The Louvre curators have accepted this new chronology, which means it took the artist 15 years to create the Mona Lisa and Saint Anne.

“For us, one of Leonardo’s fundamental traits is that he pursued the execution of his works over a very, very long time, which is to say that, for us, he was not at all someone disinterested in procedural execution, for whom painting was something abstract that came after the conceptual work,” Frank says. “To the contrary, the execution was essential for him. Once he found an idea, he reworked it infinitely, and that was really what was at the heart of his life. So we have put the science of painting, the divine diversion, back at the very heart of Leonardo’s life.”

“Leonardo da Vinci” is on view at the Louvre, Rue de Rivoli, 75001 Paris, France, October 24, 2019,–February 4, 2020.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.