In these turbulent times, creativity and empathy are more necessary than ever to bridge divides and find solutions. Artnet News’s Art and Empathy Project is an ongoing investigation into how the art world can help enhance emotional intelligence, drawing insights and inspiration from creatives, thought leaders, and great works of art.

What the gallery says: “Both [Josef] Albers and [Giorgio] Morandi are best known for their decades-long elaborations of singular motifs: From 1950 until his death in 1976, Albers employed his nested square format to experiment with endless chromatic combinations and perceptual effects, while Morandi, in his intimate still lifes and occasional landscapes, engaged viewers’ perceptual understanding and memory of everyday objects and spaces.

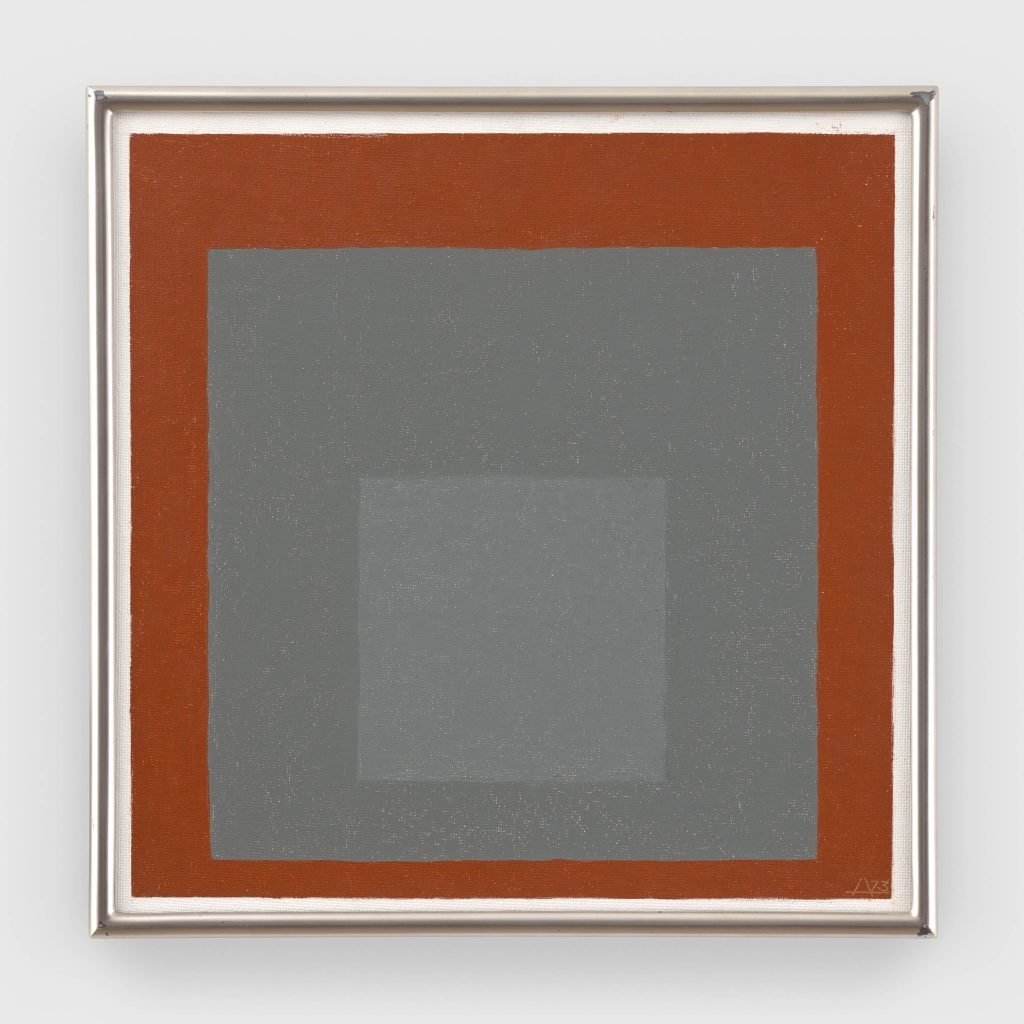

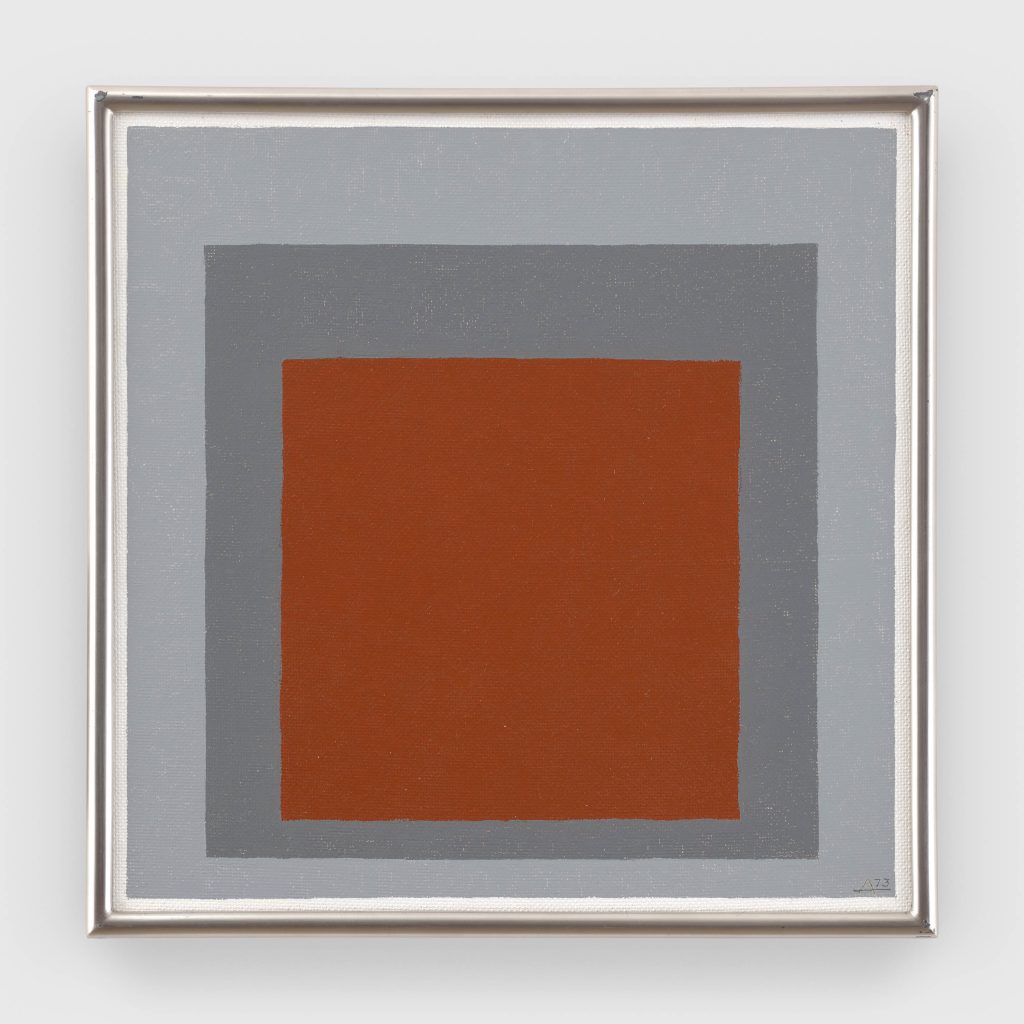

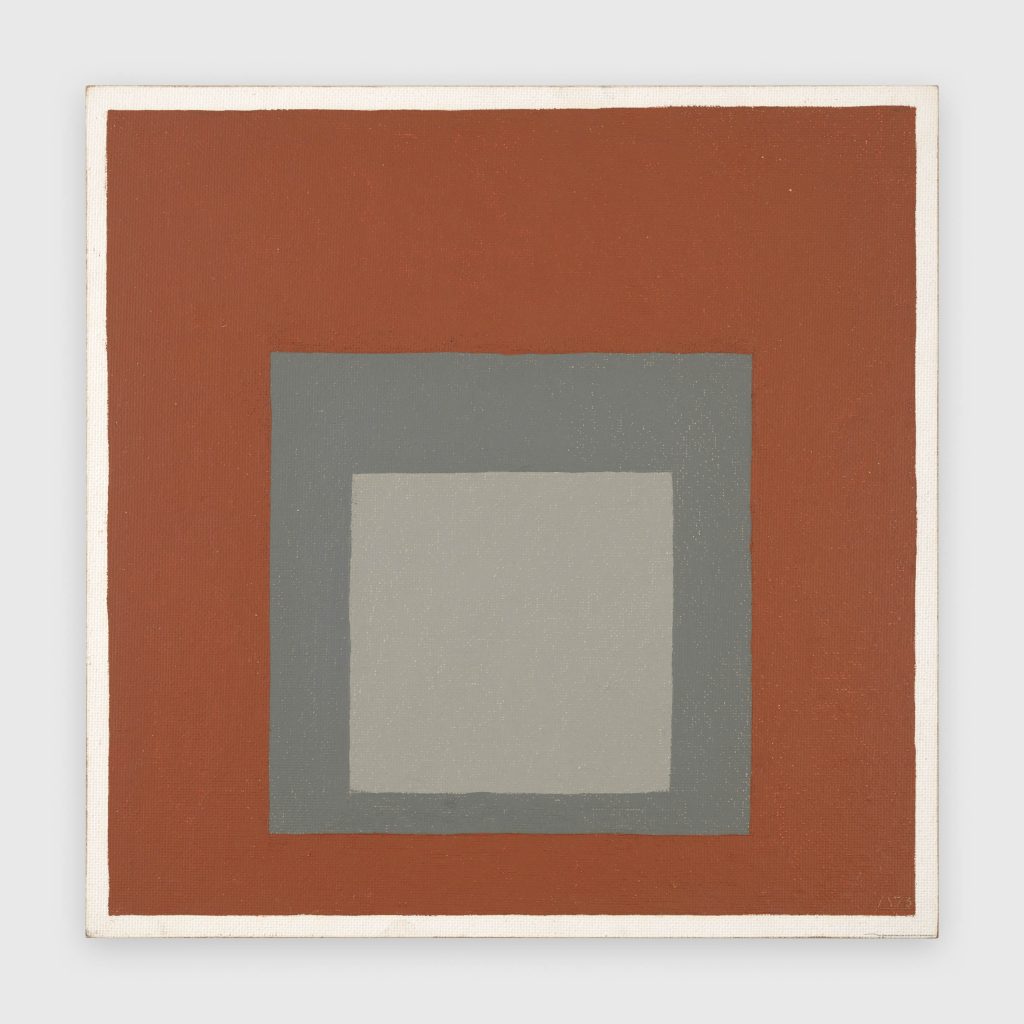

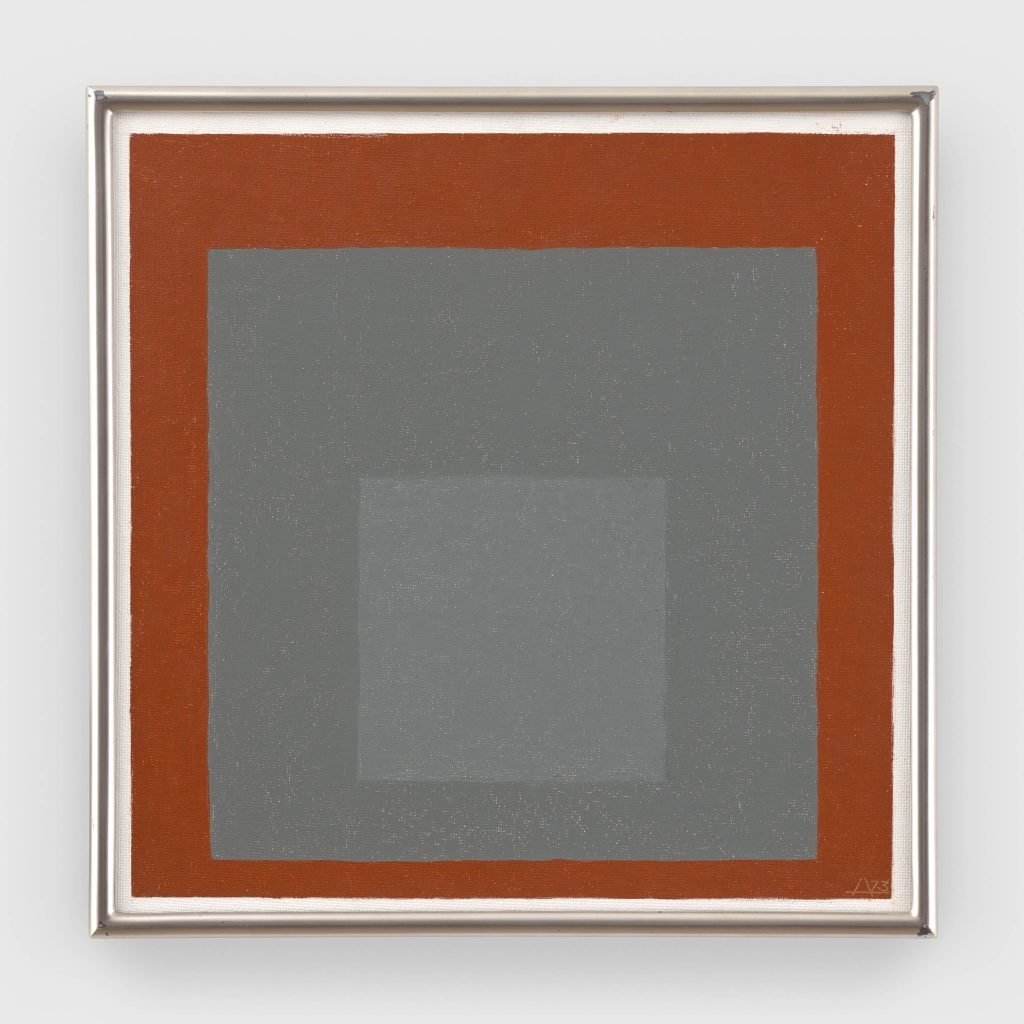

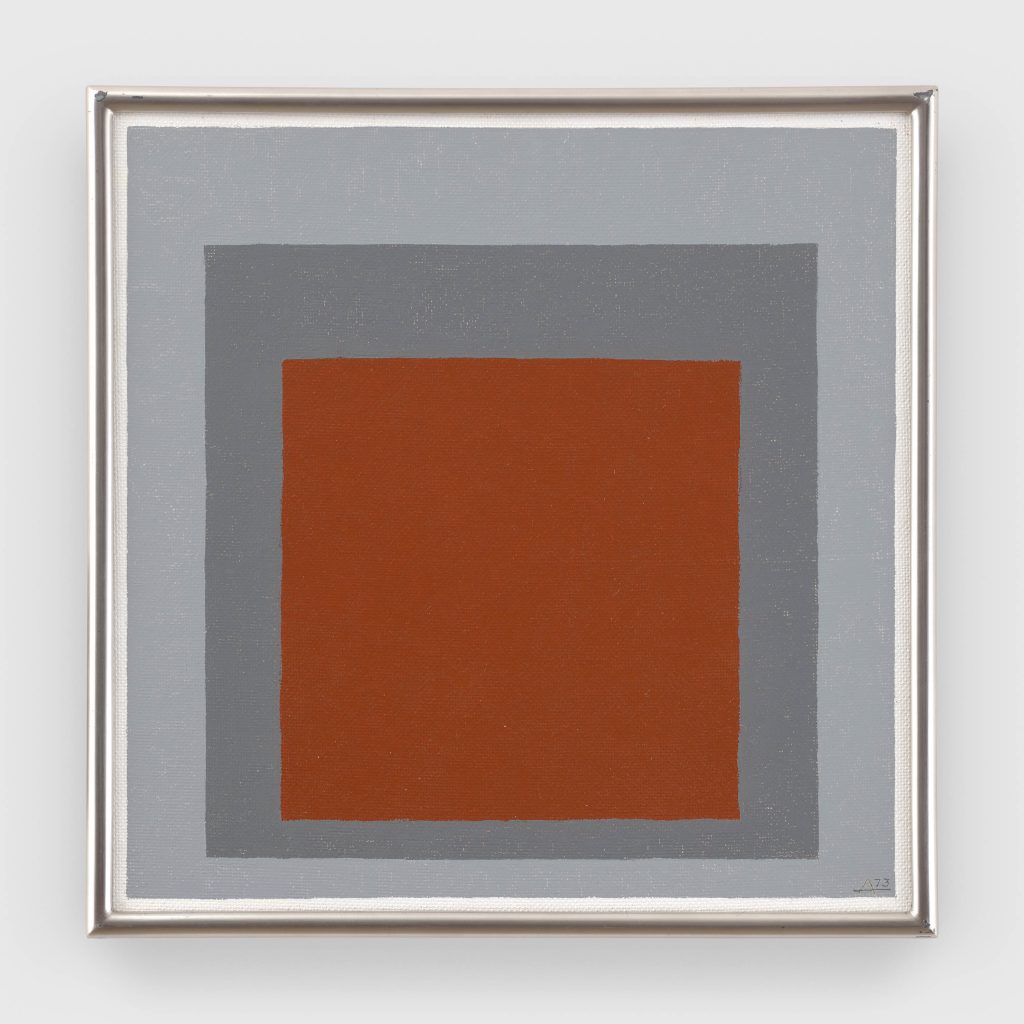

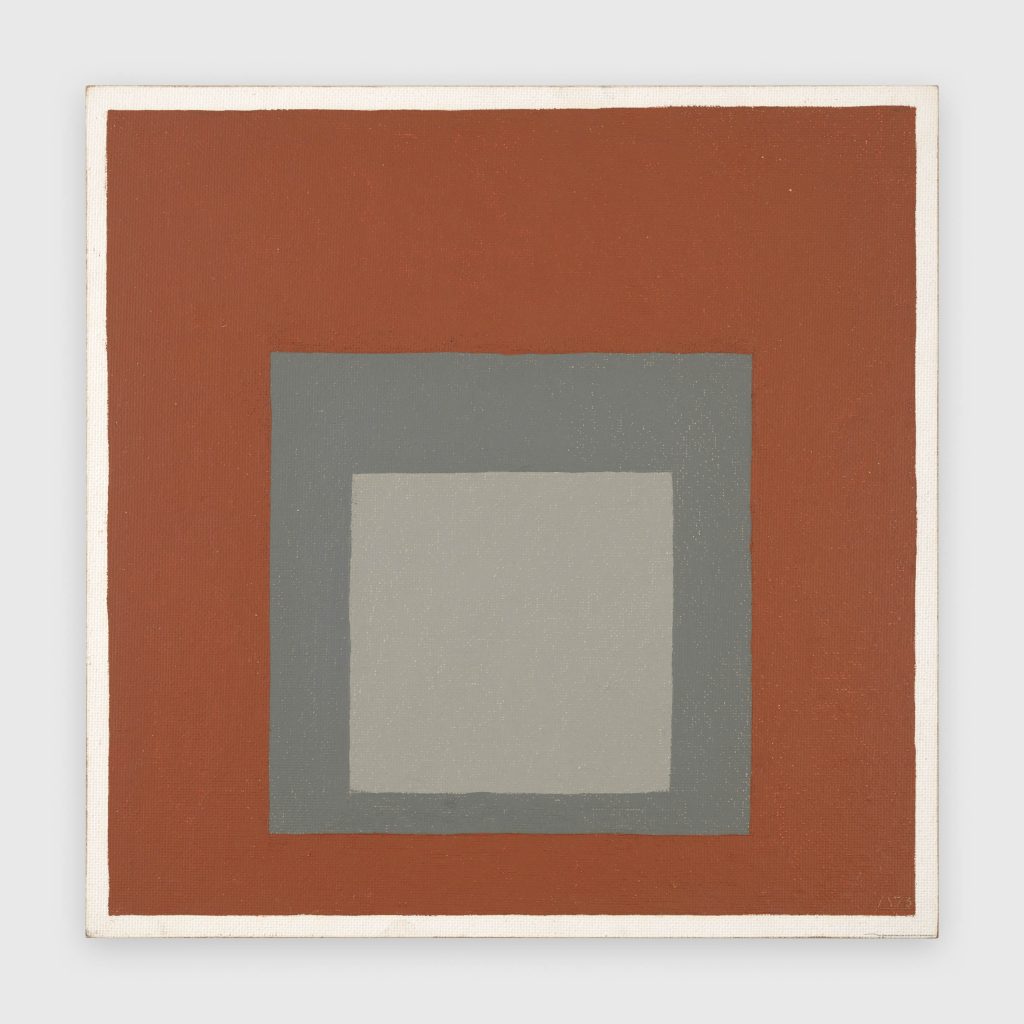

‘Albers and Morandi: Never Finished’ will put each artist’s distinctive treatment of color, shape, form, morphology, and seriality in dialogue. Looking specifically at the stunning palettes of Morandi’s celebrated tabletop still lifes depicting humble vessels and vases and Albers’s seminal ‘Homage to the Square’ series, the exhibition will elucidate how the two artists’ careful daily acts of duration and devotion allowed each to highlight the essence of color and the endless possibilities of their respective visual motifs.”

Why it’s worth a look: Albers and Morandi, contemporaries born two years apart, diverged in many ways. While Albers focused, especially at the end of his life, on a proto-postmodern exploration of relationships, stressing that all things are affected by their context, Morandi brooded over still lifes and landscapes, somehow managing to capture the anxieties of the 20th century in seemingly quiet forms.

Both artists were concerned with color especially, and each one used it as a structuring and restricting element: Albers in his sometimes brash juxtapositions of blocks of pigment, Morandi in his more subtle, often monochrome palette. This show reveals the underlying mechanics that drove the artists in their differing yet crucially overlapping pursuits. Beyond that, the exhibition also reveals the emotional intelligence of two artists who figured out ways to be enormously emotive without using expressive marks.

How it can be used as an empathy workout: Both artists believed in cultivating observational powers to better understand the world around them. As Morandi once noted: “One can travel the world and see nothing. To achieve understanding, it is necessary not to see many things, but to look hard at what you do see.” And for Albers, the interactions between a work’s materials allowed the development of what he called “visual empathy.”

“Respect the other material, or color—or your neighbor,” he told his students.

Make sure to take time to look at each work carefully, noticing how the artists captured light, shadow, and their objects’ relationships to the spaces in which they sit. A sense of lonely beauty runs through Morandi’s 1947 work Fiora, for example, while Albers’s 1954 Study to Homage to the Square captures a kinetic kind of energy in bright, warm-toned hues.

What it looks like:

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta (Still Life) (1957). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta (Still Life) (1953). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Giorgio Morandi, Fiori (Flowers) (1947). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Josef Albers, Study to Homage to the Square (1973). © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and David Zwirner.

Josef Albers, Study to Homage to the Square (1973). © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and David Zwirner.

Josef Albers, Study to Homage to the Square (1973). © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and David Zwirner.

Josef Albers, Study to Homage to the Square (1954). © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and David Zwirner.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.