In the vast, gilded cupola hall of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum on Monday evening, filmmaker Wes Anderson stood in an eggplant-colored corduroy suit before hundreds of Austrians, as well as friends Tilda Swinton and Jason Schwartzman.

“We thought it was going to be easy,” Anderson admitted, speaking of his foray into curating with his wife, designer and novelist Juman Malouf. “Of course, we were wrong. But we didn’t expect to be so wrong for so long.”

Indeed, the first-ever curated exhibition by the filmmaker and Malouf was a challenge not only for the duo, but also for the museum. “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures,” which opened on November 5, is the largest exhibition the institution has ever done. (Indeed, in terms of the number of objects included, it is bigger even than the hugely ambitious Bruegel exhibition in the neighboring wing.)

The couple pulled from all 14 of the museum’s massive collections, which include some 4.5 million objects in total and span 5,000 years. From these, Anderson and Malouf chose and arranged a staggering 430 pieces, almost half of which had never been seen before. Most were tucked away (some without inventory numbers) in the darkest corners of the 19th-century building. (The show will travel to Fondazione Prada in Milan next spring.)

Exterior view of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. ©KHM-Museumsverband

“Their favorite part of the museum was the things that are sleeping softly on white cushions on shelf number 42 on the third floor of a storage room,” says Jasper Sharp, an adjunct curator of modern and contemporary art at the museum. The duo’s carte blanche invitation to create a show at the Kunsthistorisches originated with Sharp during a chance encounter through a mutual friend.

The project is the latest in a series of artist-curated exhibitions Sharp has been spearheading at the elegant Habsburg-era institution. Ed Ruscha and Edmund de Waal were the first two contemporary artists invited to put their own twist on its holdings. Since the museum is no longer updating its collection, the series is an experimental way to find new possibilities for visitors to experience its world-renowned trove of objects.

Anderson and Malouf, of course, are not really artists. But the cultural couple had been coming to the museum for years and were already steeped in its treasures. Or so they thought.

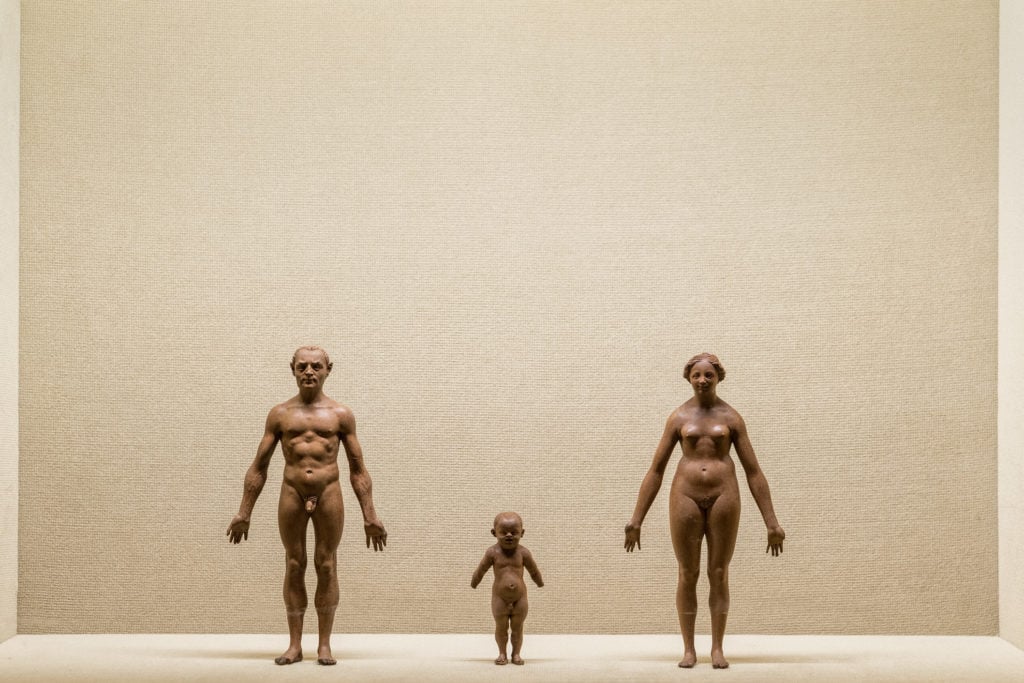

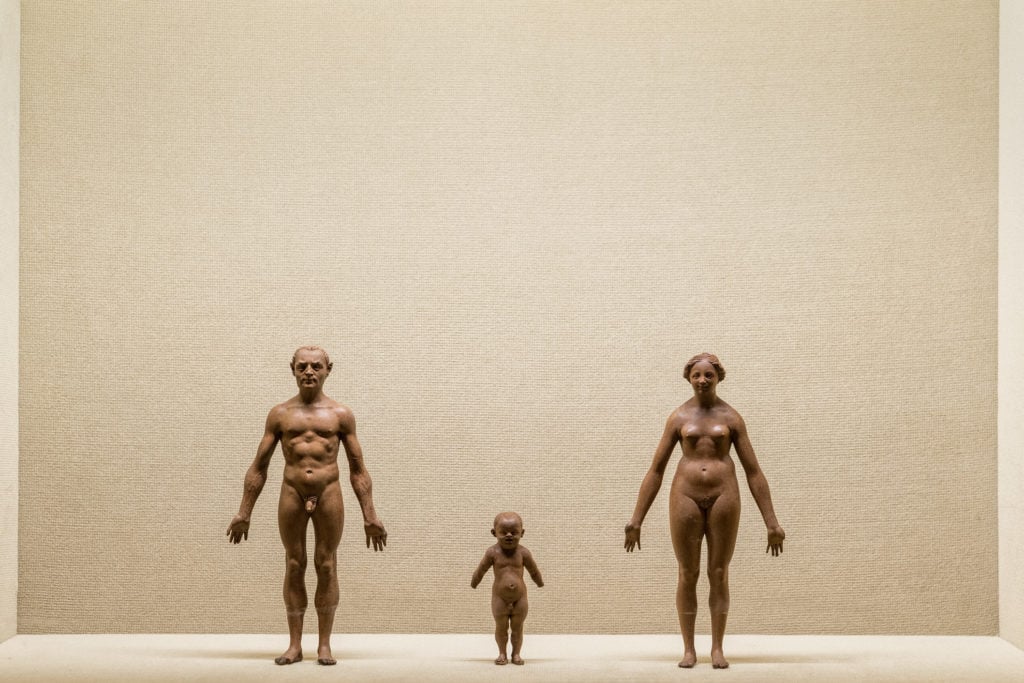

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

A Show About Misfits

So what does an art show co-organized by Wes Anderson look like? True to his auteur style, it’s a totally quirky presentation of affectionate misfits. Arranged into constellations that break all the art-historical rules, it stands as an homage to overlooked items, a somewhat novel way of curating that, knowing the filmmaker’s offbeat aesthetic, is altogether unsurprising.

In their first meeting at the museum, Sharp recalls how the couple would glide right past the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s larger-than-life gold-framed war heroes or towering masterpieces of baroque saints. Instead, they were captivated by the oddities in the museum’s Kunstkammer (translated: art cabinet), a holding of stunning curiosities collected by Austrian monarchs over centuries; it’s the most significant of its kind in the world.

But the objects in their show are not necessarily dazzling. The oldest object is a gnarled piece of fossilized wood dating back hundreds of thousands of years. Then there are three dark green emu eggs that were laid especially for the show six weeks before the opening. They sit in a custom-built vitrine which looks a bit like incubator in this context, across from the diminutive Spitzmaus (shrew) mummy that gives the exhibition its name.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

On a walk through the exhibition, Sharp paused in front of the shrew’s tiny 4th century BC tomb, which is the size of a large shoe box and stands in the center of the show. “It’s like chubby ballerina who can’t dance very well having her one night as the white swan,” said the British curator. Normally, the little coffin sits quietly in a row of several other tombs in the Egyptian wing.

Sharp estimates that only one in 5,000 visitors may have taken a moment to even notice the Spitzmaus before Anderson and Malouf pulled it from the sidelines.

Everything on view here follows this pattern. There is a series of three large portraits of Petrus Gonsalvus and his family from the 16th century, who were all afflicted with hypertrichosis and were completely covered in hair from head to toe. Another room, dedicated to vessel-like objects, includes only the suitcase for the war robe of a Korean Prince. Nearby, a glass that belonged Napoleon sits, in its case.

Meanwhile, a row of 22 miniature busts spans styles and centuries, organized not by chronology or context, but by size. Broken limbs from unknown sculptures are given their own vitrines too, alongside a wayward finger from an early Roman-era statue that is also unknown.

“These are things that would not normally be shown,” Sharp notes. Sometimes, objects like these were just gifted to the museum, even though they aren’t exactly prized possessions.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

Outsiders Curating Outsiders

Perhaps the duo’s penchant for the collection’s oddball items also stems from their own awareness of being outsiders in a prestigious establishment replete with trained art historians, curators, and conservators.

One senior curator said that some of museum staff were skeptical of the project at first. “We would get an email from Wes asking, ‘Do you have a list of green objects? Could you send us a list of everything you have that is yellow?’ Our data system does not have these categories.”

Because of this, the curators and conservators had to manually search their storage, an often painstaking process due climate controls and the condition checks needed, neither of which Anderson or Malouf were aware of.

The extra labor required was taxing, but the duo’s alternative criteria had a welcome side effect: It leveled the usual hierarchies. Several staff members said it resulted in new revelations. They just had to “learn to unlearn” their ways of working.

Wes Anderson, Juman Malouf, and Kunsthistorisches Museum director Sabine Haag in their first-ever curated exhibition. © KHM-Museumsverband. Photo: Rafaela Proell.

The presentation of their curated sections was also astoundingly direct, without a single title or didactic panel. (There was a booklet to walk around with, though the day before the opening the two curators were still moving things around, so it was slightly out of sync.)

Boxed-off, color-coded “rooms” were set up like self-contained tableaux: A room focused on fauna affectionately recalled Anderson’s love of adorable, diminutive creatures. The characters and landscapes of 2009’s Fantastic Mr. Fox or this year’s Isle of Dogs were echoed in the yellow mischievous eyes of Cat, an 18th-century German painting by an unknown artist, which felt like it could have been made this year.

Across from Cat was a circa 1663 painting called A Malformed Deer, depicting a too-large rendition of the animal dominating an otherwise normal, pastoral landscape. One could have imagined either work featured somewhere in the background of the various rooms of Anderson’s Budapest Hotel.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM Museumsverband.

Another room highlights curious paintings of well-fed aristocratic children (one curator pointed out how the room was carpeted, making it quieter, like a nursery). Another contained precious green stones and jeweled glass, miniature sculptures, and a green silk dress worn by a famous Viennese actress in the 1970s.

Anderson acknowledges some of the institutional skepticism in his cheeky opening statement: “One of the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s most senior curators […] at first failed to detect some of the, we thought, more blatant connections; and, even after we pointed out most of them, still question their curatorial validity.”

But, the filmmaker says, this show was about trial and error. He and Malouf seemed to be quite honestly unafraid of taking risks and making mistakes.

In the “wooden” room, a masterfully carved sculpture of Jesus Christ stands beside a wooden, tribal-looking figurine from the neighboring World Museum. They are worlds apart, but standing in the same position.

“Both of these things have a certain magic,” explained the curator. “Together, they have even more magic. Anderson and Malouf helped us see that.”

See more views from the exhibition below.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

Exhibition view of “Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures.” © KHM-Museumsverband.

“Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures from the Kunsthistorisches Museum” curated by Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf is on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum until April 28, 2019.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.