Art Fairs

Maurizio Cattelan Is on a Mission to Turn Reclusive Wisconsin Artist Eugene Von Bruenchenhein Into a Household Name

Cattelan is behind a presentation of the work of Eugene Von Bruenchenhein at Paris's Outsider Art Fair.

Cattelan is behind a presentation of the work of Eugene Von Bruenchenhein at Paris's Outsider Art Fair.

To most of the people who saw him around Milwaukee, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910–83) was eking out a living working at a florist and then a bakery. After developing a respiratory problem, likely through exposure to flour dust, he stopped working at the age of 49 and subsisted on social security.

Yet Von Bruenchenhein had a very different life behind closed doors: He was a prolific, self-taught multimedia artist. In addition to taking racy photographs of his wife Marie, he made vibrant, phantasmagorical paintings merging ideas about nature, geopolitics, sci-fi, and the apocalypse. He also constructed small sculptures from chicken bones.

Von Bruenchenhein’s work was unrecognized in his lifetime and repeated attempts to gain the attention of local dealers were met with silence. It was only after his death, when a family friend introduced his work to a curator at the Milwaukee Museum of Art, that his broad oeuvre started to attract attention.

Now, Von Bruenchenhein has found another unlikely champion: Maurizio Cattelan. The Italian artist has joined forces with Marta Papini, artistic organizer of Cecilia Alemani’s Venice Biennale exhibition “The Milk of Dreams,” to organize a special presentation of Von Bruenchenhein’s work at the Outsider Art Fair in Paris. Held in Atelier Richelieu, a short stroll away from the Louvre, this is the tenth edition of the fair, which runs from September 16 through 18.

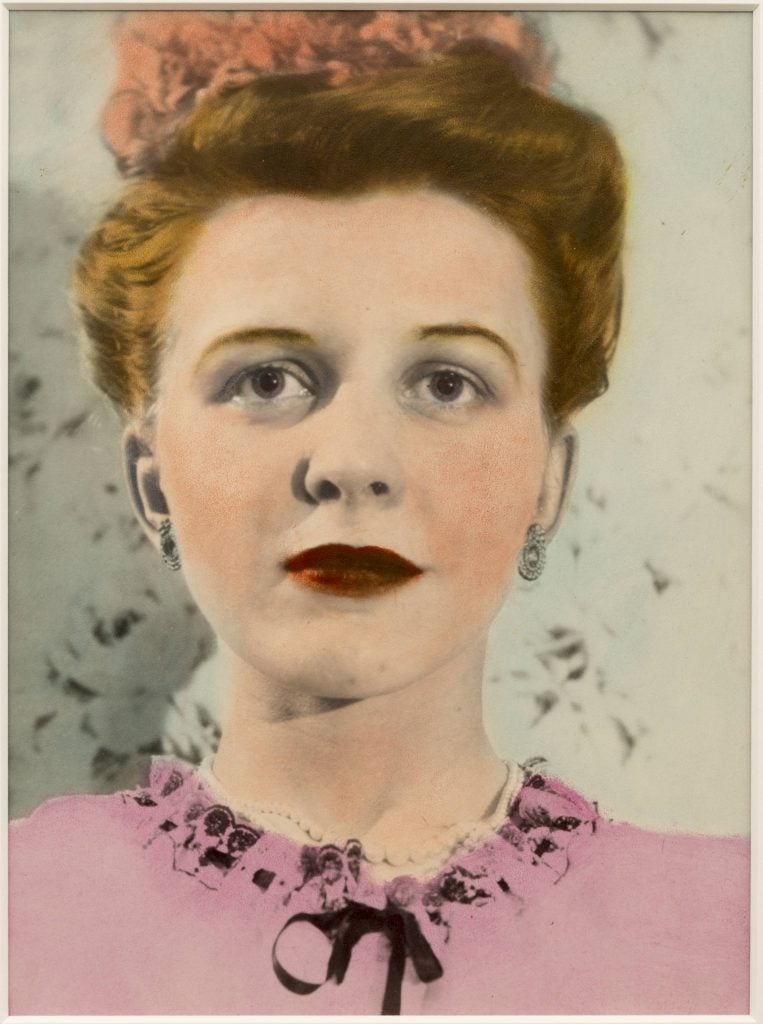

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, No. 795, April 10, 1959 (1959). Collection of KAWS.

Cattelan has been mesmerized by Von Bruenchenhein’s work ever since he discovered it in a group show in Chelsea many years ago. “His paintings impressed my memory in the same way that the light does with the film in an old camera,” Cattelan told Artnet News. “I couldn’t stop thinking about them.”

Meanwhile, dealer Andrew Edlin, who is also CEO of Outsider Art Fair, said: “Maurizio has loved this field and attended our fair for as long as I can remember. His excitement about Eugene Von Bruenchenhein was unmistakable when he came to see our last solo show of his work at the gallery” in December 2020.

On view in the OAF Curated Space section of the fair are nine paintings that Von Bruenchenhein made between 1956 and 1960. Although at the time his audience was limited to close family and friends, the artist numbered and dated all of the canvases, recording the exact day in slanted, looped handwriting across the picture. He would paint frenetically, often completing a work in a single day. This inspired Cattelan to bring historical context to the presentation by displaying each work below the front page of The New York Times from that same date.

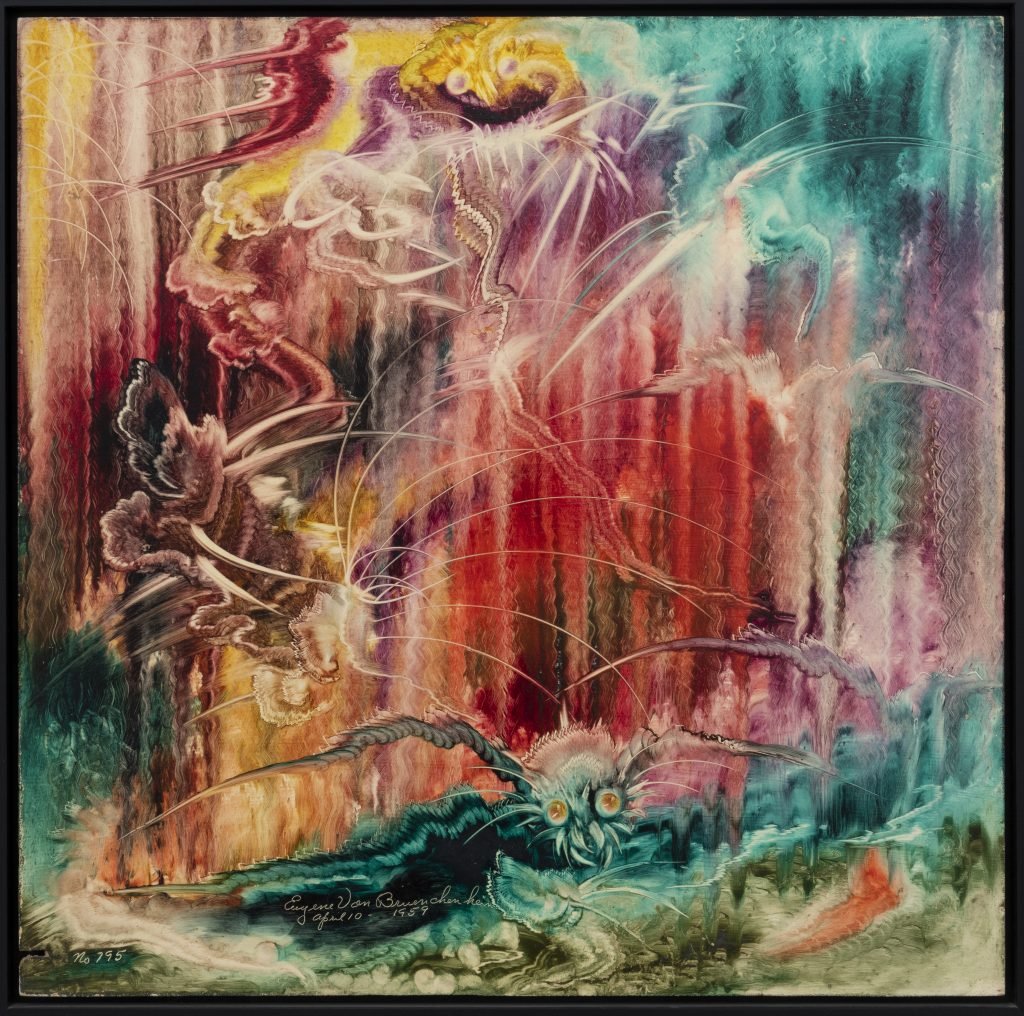

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Untitled (Sept 19 – 65) (1965). Photo courtesy of the Outsider Art Fair.

“Recently, I saw an exhibition of conceptual art from the 1960s that made me think Von Bruenchenhein’s work might be re-read in this sense; he would date every painting with the exact day, as On Kawara did all his life,” Cattelan explained. “When I spoke to Andrew Edlin about this, he proposed that we curate a show that would suggest this interpretation.”

Cattelan’s idea of pairing the paintings with the New York Times enables us to see what issues were preoccupying Von Bruenchenhein at the time. For instance, Wand of the Genii, Nov 5, 1956 depicts concentric circles in rippling pink, green, yellow, and cream exploding across the nocturnal sky above arcades of arches. The headlines of The New York Times on November 5, 1956, report on Britain and France invading Egypt “by air” during the Suez Crisis. Von Bruenchenhein’s foreboding painting could be read as a meditation on the air strike’s threat to Egyptian heritage.

This painting is also the only one for sale in the display. Priced at €65,000, it is one of the more expensive pieces at the fair, where many works are in the four-figure range. Edlin sourced Von Bruenchenhein’s other paintings from private collections; five of them belong to the artist KAWS.

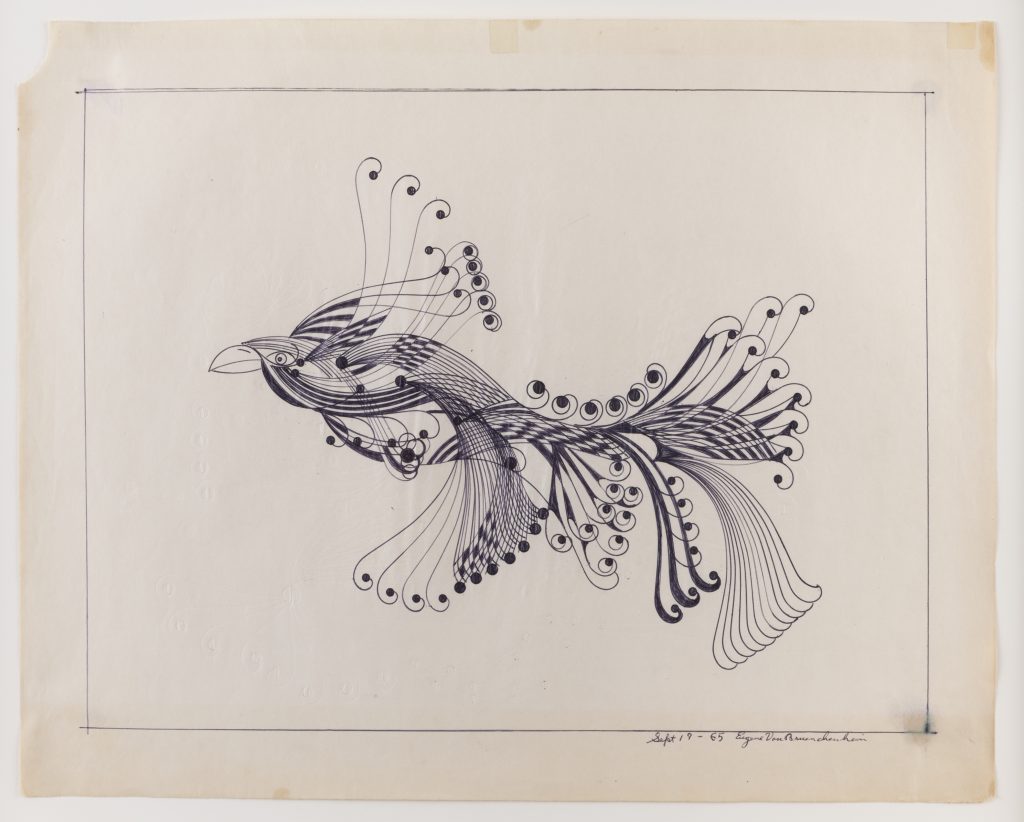

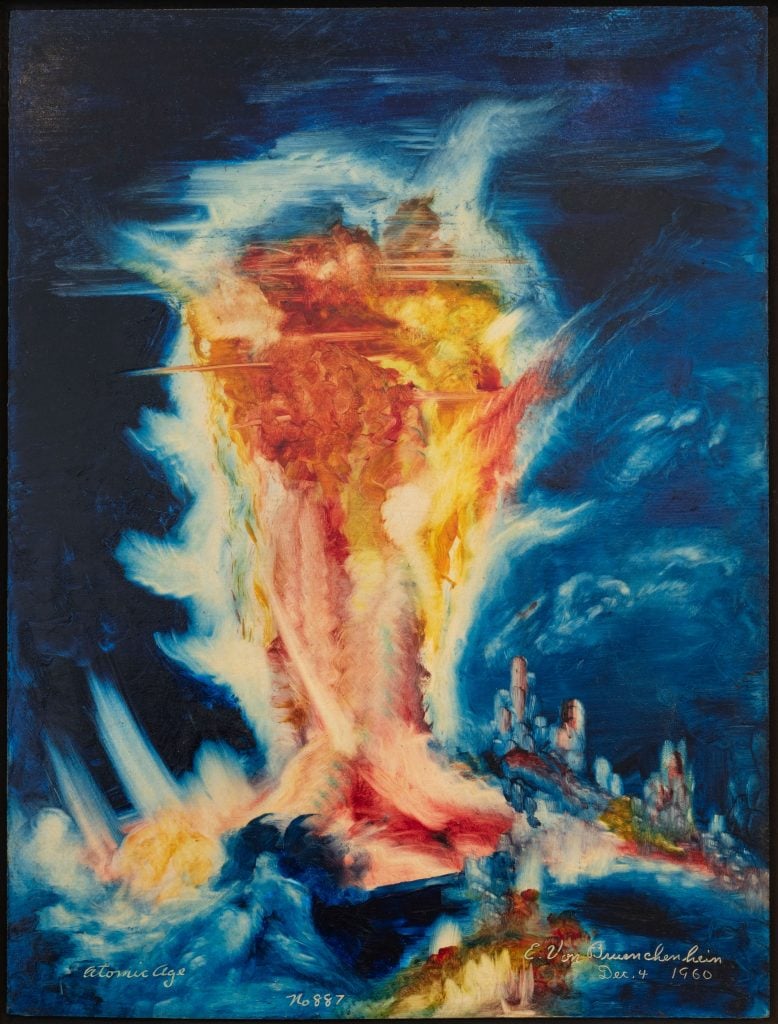

Sometimes, the link with the front pages of The New York Times is tenuous. No. 535, Jan 1, 1957—a dynamic painting with dragon-like creatures amid swirling abstract elements—seems unrelated to any specific news event. Meanwhile, Atomic Age (No. 887, December 4, 1960), which depicts a blazing mushroom cloud, seems to recall the first French nuclear test, codenamed Gerboise Bleue, from February 1960.

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Atomic Age (No. 887, December 4, 1960) (1960). Collection Joshua Rechnitz.

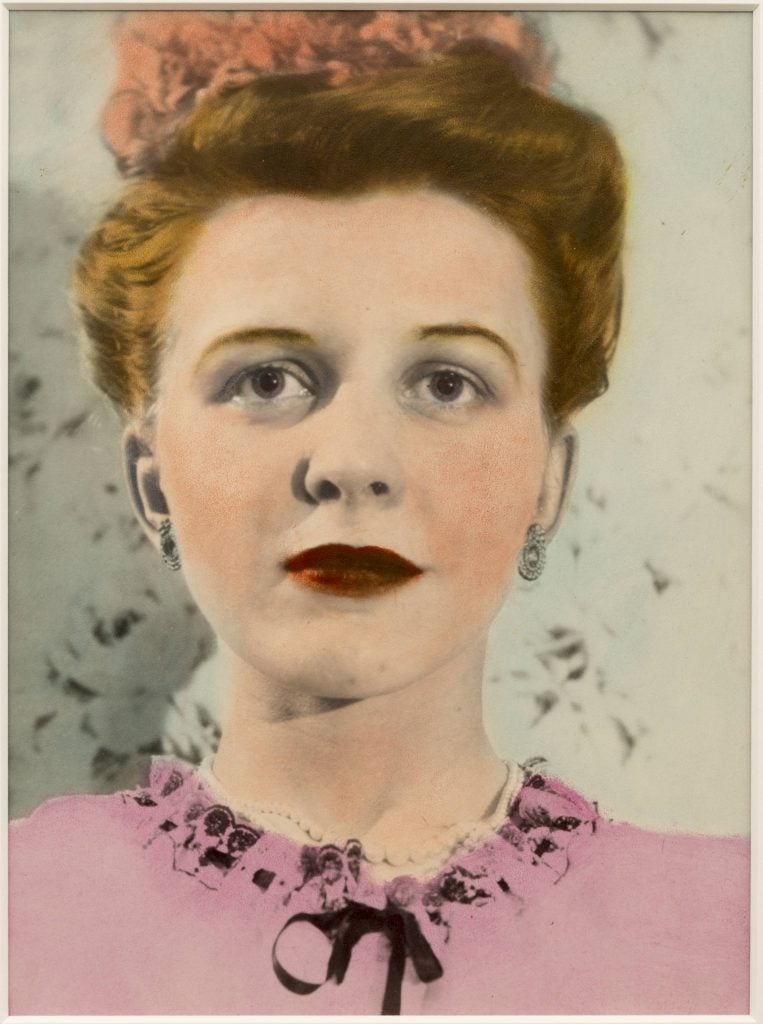

Also on offer are several drawings, priced at €12,000 each, and photographs, including a black-and-white portrait of Marie topless and gazing lovingly at the camera, priced at €6,000. A self-portrait loaned from John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, is shown alongside a similarly styled portrait of Marie. “I don’t believe that Von Bruenchenhein would have been so prolific if it wasn’t for Marie,” Cattelan said.

Indeed, Von Bruenchenhein is perhaps best-known for his pin-up photographs of Marie. A selection of these images figured in the exhibition “Alternative Guide to the Universe” at the Hayward Gallery in 2013. That same year, several of the artist’s futuristic paintings appeared in the central Venice Biennale exhibition, “The Encyclopedic Palace,” curated by Massimiliano Gioni. Von Bruenchenhein’s work was the subject of a solo show at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, which opened in 2010.

It is the consistency of Von Bruenchenhein’s visual language that appeals to Papini. “What I find fascinating about his practice is the visual coherence despite the diversity of media he adopted,” she said. “Whether it was paintings or bone sculptures, photographs or clay vessels, one can always see a fil rouge that connects one piece to the other, as if they were conceived to live together.”

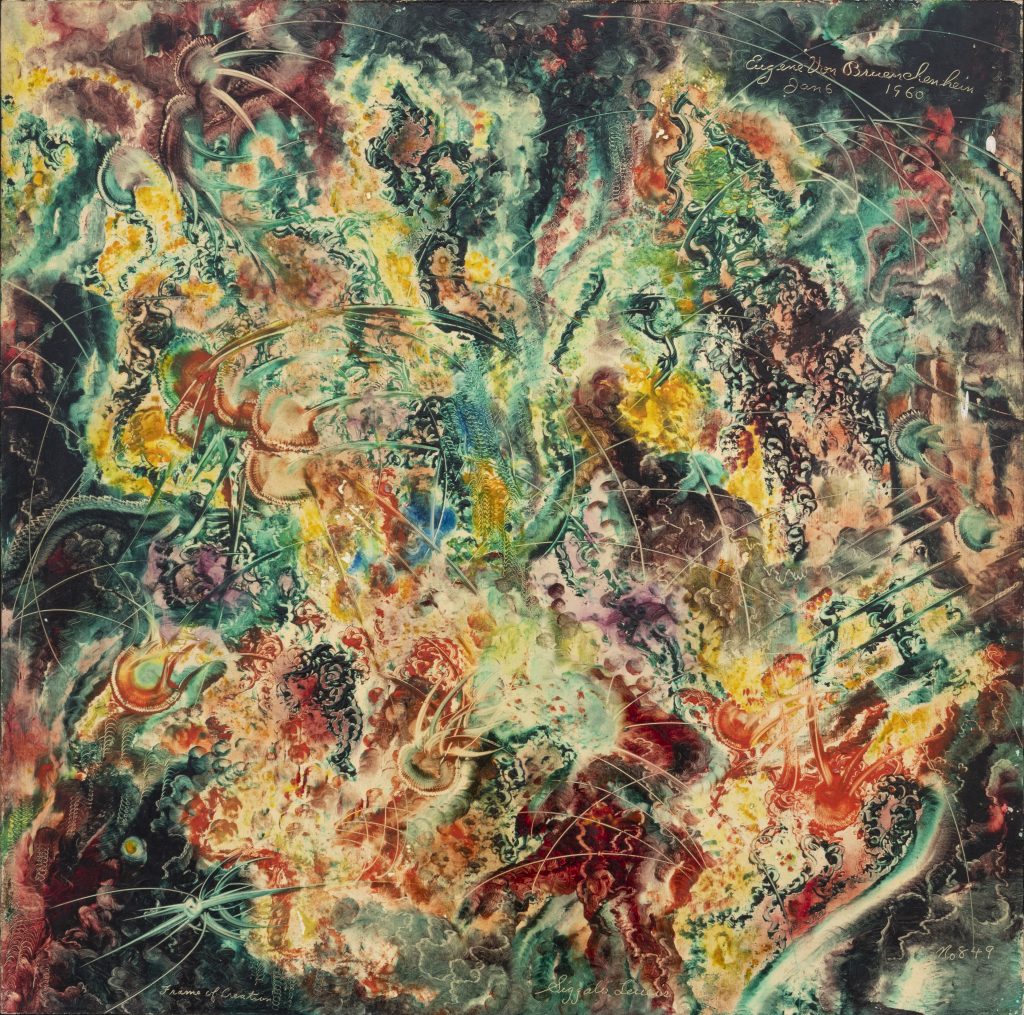

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, No. 849, Jan 6, 1960 (1960). Collection of KAWS.

Nonetheless, Von Bruenchenhein is still considered an outsider artist—something that Cattelan is extremely keen to address. “I believe he was an outsider only because no one let his work be in the “official” art world before his death, even if he tried hard to get that kind of recognition for his whole life,” Cattelan said. “This is so sad that I feel we need to repair it. I wish he could see how much his work is loved now.”

The market has been warming up, too. Although Von Bruechenhein’s work is still traded relatively rarely at auction—only 31 of his works have ever hit the block, according to the Artnet Price Database—his prices are climbing. His auction record of $47,500 was set this February at Christie’s New York for a small oil painting from 1958, which handily exceeded the $30,000 high estimate.

On a personal note, Cattelan added: “I wish I had half of his determination and self-confidence. He was so convinced about what he was doing that he would not stop and give up. I’m very insecure all the time, and looking back at my work I see many mistakes and things that I would love to change. I don’t think my work has anything to do with his and probably this is what fascinates me the most.”