“What I wanted 20 years ago is happening today,” says the art dealer LaTiesha Fazakas.

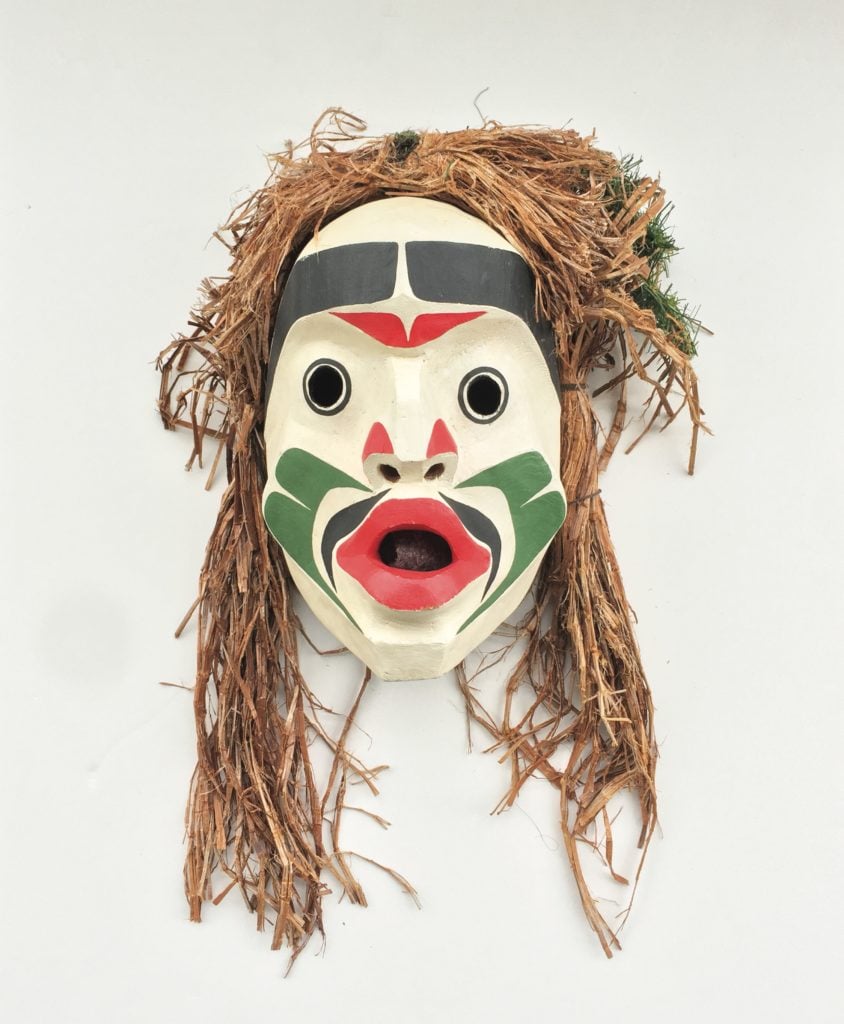

Having just landed in New York from Vancouver when she spoke with Artnet News yesterday, Fazakas was gearing up for her debut at the annual Independent art fair, one of nine major fairs dotting New York City this week. Fazakas will be showing work by the late Beau Dick, a Kwakwaka’wakw Northwest Coast artist and chief from Alert Bay, British Columbia (his name translates to “big, great whale,”) who has drawn acclaim for his masks that pertain to ceremonial dances.

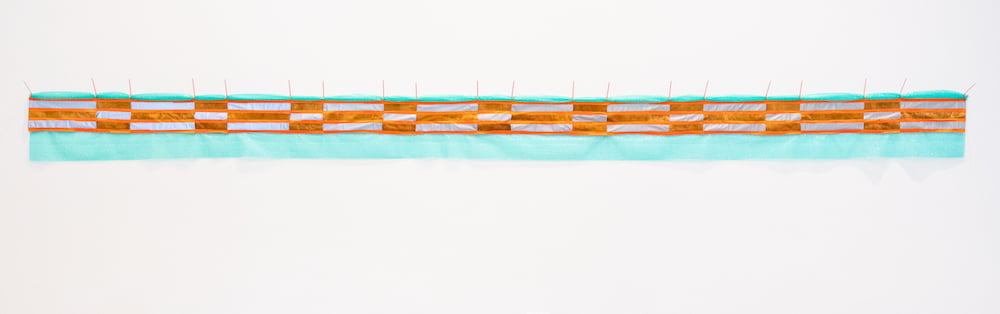

She will also show work by Dick’s longtime assistant Cole Speck, an artist who grew up on the Namgis reserve on Alert Bay, and wall pieces and sculptures by Maureen Gruben, an Inuvialuit artist who has been part of recent shows at the National Gallery of Canada and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

After decades of being pushed to the sidelines or lumped together in group shows with narrowly defined labels and parameters, work by contemporary Native American, First Nation, and other indigenous artists is finally drawing more serious and widespread institutional interest, critical acclaim, and rising prices.

“Museums and critics seem to be discovering these artists hiding in plain sight,” said David Penney, associate director for museum scholarship at the National Museum of the American Indian, which is part of the Smithsonian. “They are largely overlooked by the art critic community, American museums, and contemporary art centers. They show at museums that focus on American Indian content and their gallery representation are those who specialize with indigenous or ‘minority’ artists.”

Some of the more established First Nation and Native American artists he names include Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kay WalkingStick, Robert Houle, Shelley Niro, James Lavadour, Jeffrey Gibson, Marie Watt, Kent Monkman, Virgil Ortiz, and a collective called Post Commodity.

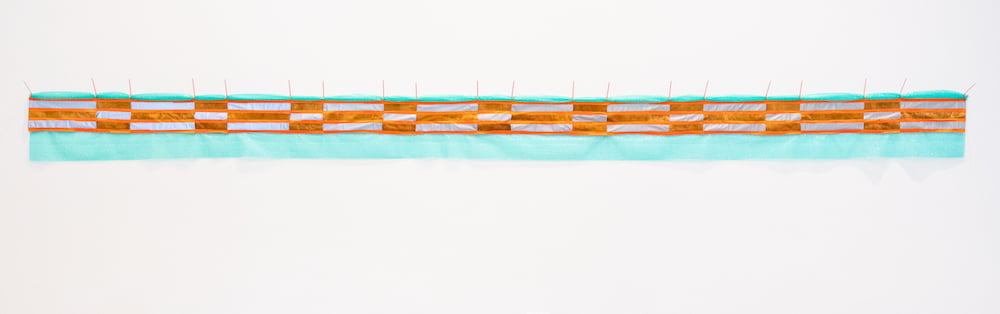

Marueen Gruben, Untitled (Delta Trim) (2018). Photo by Kyra Kordoski. Image courtesy of the artist and Fazakas Gallery, Vancouver.

Of course that is slowly starting to change now, some observers say. A few years ago, Dick’s arresting mixed-media ceremonial masks at the NADA art fair caught the eye of New York Times critic Roberta Smith, who subsequently tweeted that they were the best find at the fair. (He was also featured in documenta in 2017.)

“These are rich voices to be heard and so much interesting work to be engaged with and to explore. It’s finally getting out there and getting a wider voice,” says Fazakas.

A comparison of auction records and primary prices also reveals a big disconnect. For Dick, the Artnet Price Database shows 16 results, including a high of just over $14,000 for a mask sold in late 2018, at the Canadian auction house Waddington. On the primary market, prices for his work start around $10,000 to $15,000 and reach upwards of $150,000, according to Fazakas. “It’s kind of like two different animals with Northwest Coast art,” says Fazakas. “If you’re looking to buy Beau Dick’s work you’re not looking at auctions.”

There are no auction records available for Gruben, whose primary market prices range from $10,000 to $40,000, Fazakas says.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do since 2010 is rethink the context of what we see at art fairs, including what was excluded, marginalized, or left out,” said Matthew Higgs, founding curatorial advisor of Independent. “We’ve tried to introduce what I call ‘maverick’ voices. By that I mean art dealers whose programs and voices don’t necessarily follow consensus and who help shift attention.”

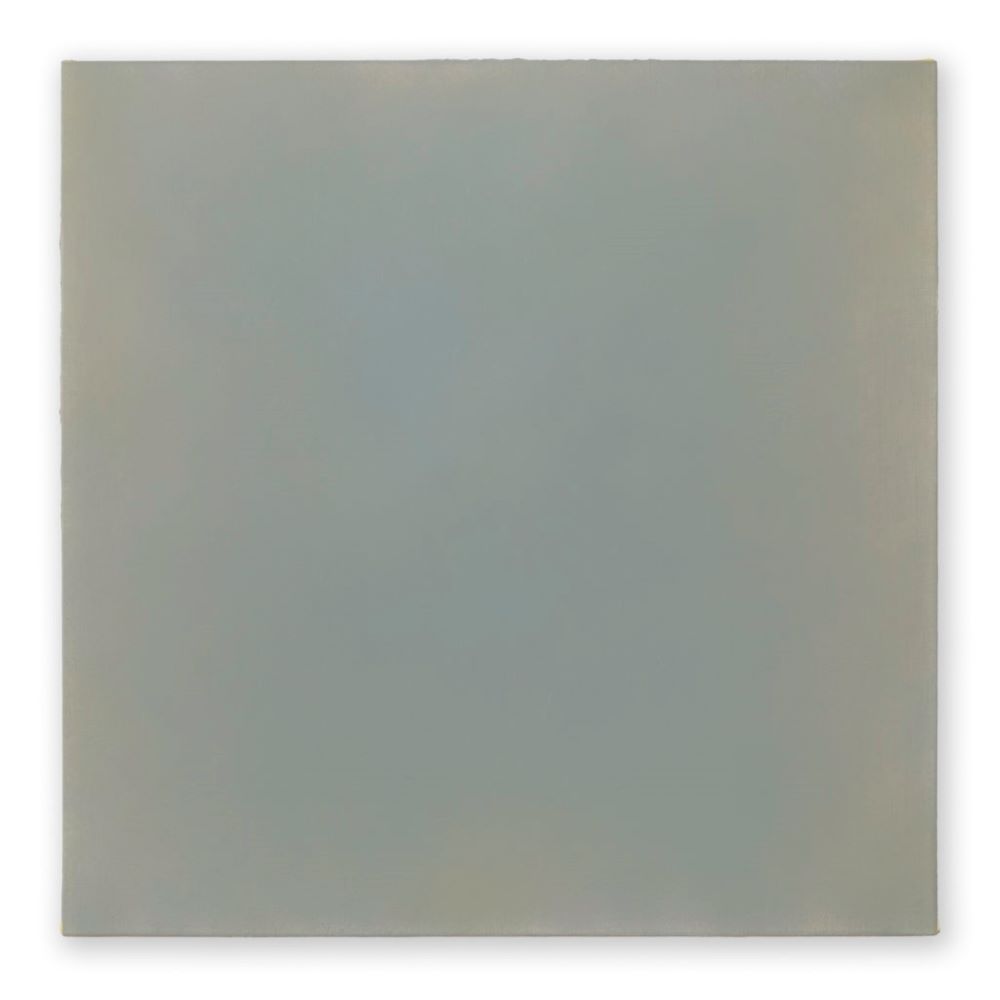

Higgs described the inclusion of Dick’s work in documenta as an encouraging sign. “Eventually these ideas start to settle and form within the mainstream. You have to be patient. We can’t accelerate that, but we can help it on its way.” This year, Franklin Parrasch will present work by Anne Appleby at Independent. Appleby is a Montana-based artist who is part Ojibwe and spent 15 years in an apprenticeship with an Ojibwe elder, learning to patiently observe nature. Her subtle paintings reflect her perceptions of natural elements over time.

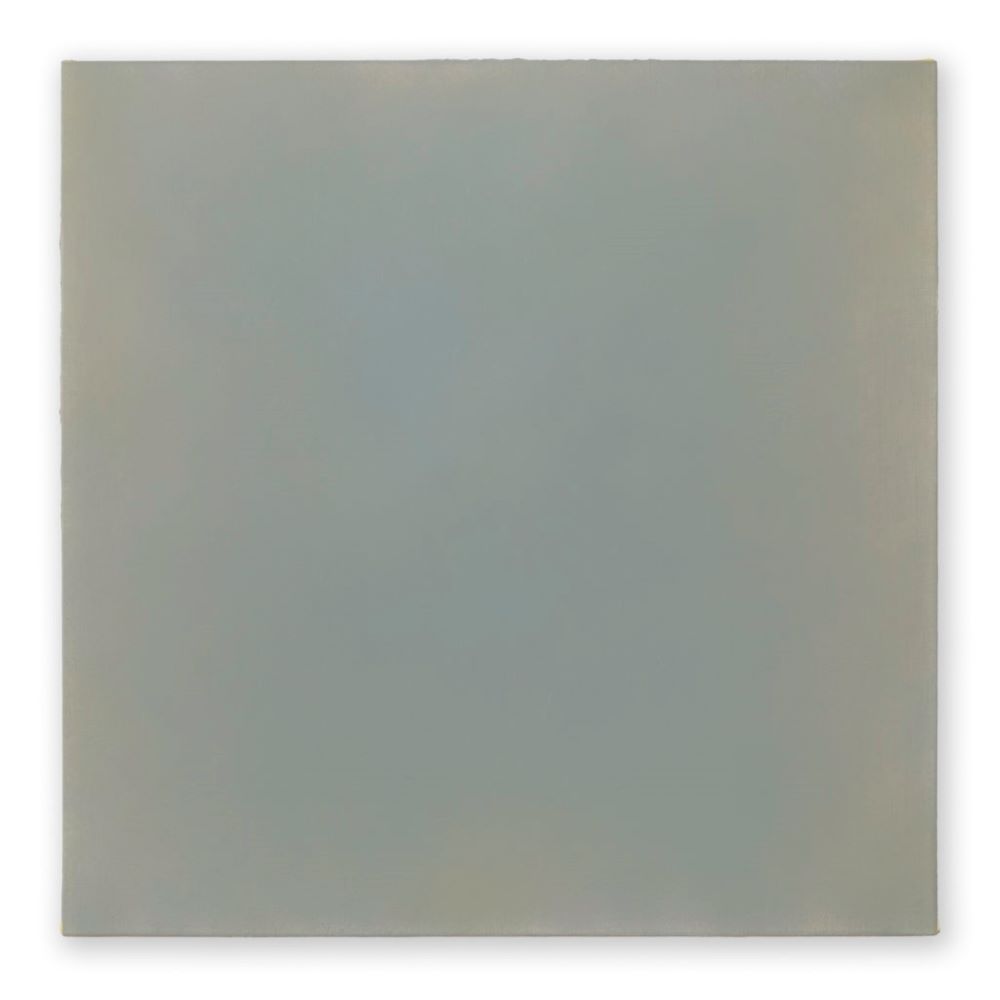

Anne Appleby, Last Light August (2019). Image courtesy of the artist and Franklin Parrasch gallery, New York and Los Angeles.

Parrasch told Artnet News that Appleby doesn’t particularly identify as First Nation despite her experience. “Her work has always been contextualized among minimalists,” he says.

Appleby’s auction record stands at $7,500 for a work sold at Bonhams Los Angeles. Parrasch said paintings at his gallery show last fall were priced at $20,000. Prices for the more recent figurative works—her “Mountain Paintings” series—that will be included in the presentation at Independent are priced between $45,000 and $55,000.

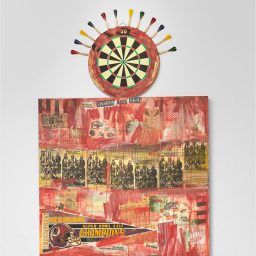

Cannupa Hanska Luger, Life is Breathtaking, Time Devours Things (2017). Image courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery.

Meanwhile, Garth Greenan Gallery will present ceramics and installations by Cannupa Hanska Luger, who is of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian descent. He has had exhibitions at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, and the Princeton University Art Museum. Luger mashes up Native American imagery with Hollywood cliches of Native culture.

“It’s obviously a really exciting thing,” said Barbara Brotherton, a curator of Native American art at the Seattle Art Museum, of the recent exposure. The museum has a long track record of showing Native American art ranging from historical to contemporary periods. “We’re just in this modern moment where it’s gaining cachet from venues like art fairs, contemporary galleries, and biennials.”

“What is contemporary Native American art, and where does it belong?” she asks. “In some ways we’re still having those discussions.”

She also notes the somewhat scattershot historical pattern of shows that depend on not-always-useful categories like geography. “There’s such great diversity among native communities and artists,” she says, “it’s really hard to determine if there is a collective voice,” she says.

“The biggest change is the tacit acknowledgment among scholars and curators of American art that Native artists are part of that larger story, just as African American artists started to become more visible during the multi-cultural 1980s,” says Penney. The Whitney recently brought out its painting by Ojibwe artist George Morrison—which it bought and put away in the 1950s—and it mounted a small installation of work by Mohawk artist Alan Michaelson. A retrospective exhibition for Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith is in the works at the museum. Meanwhile, Kent Monkman, an artist of Cree descent, recently completed a major commission for the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Nonetheless, Penney says, “these are rare, very recent developments.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.