As Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips prepare to kick off another round of livestreamed evening sales this week, much about these productions is different from years’ past.

But one thing hasn’t changed: work by women is still severely underrepresented.

So far this year, works by men have made up about 90 percent of the lots offered, about 90 percent of the works sold, and about 90 percent of the money generated by the Big Three houses’ New York and London evening auctions. Men outnumbered women 85 to 15 on the list of 100 top-selling artists at auction in the first half of 2020.

There is a similarly distressing bias toward male artists in museum collections, in part because decision-makers tend to be disproportionately male.

But a deeper investigation also reveals that the motivations of many female collectors, and their approach to creating value, may be different from those of many men.

Barbara Lee, the founder and president of the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, describes her collecting as “an extension of my social activism—I prioritize being a champion for artists who confront the status quo and provide powerful commentary on how they experience the world. There is still a dramatic disparity in the way works by men and women are valued, priced, and collected.”

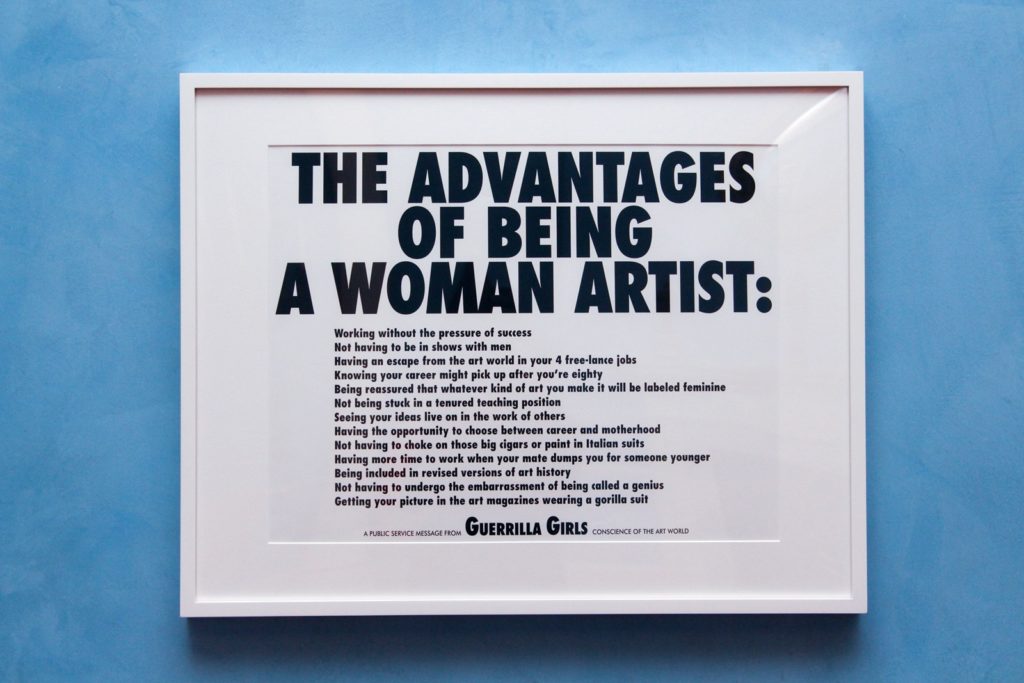

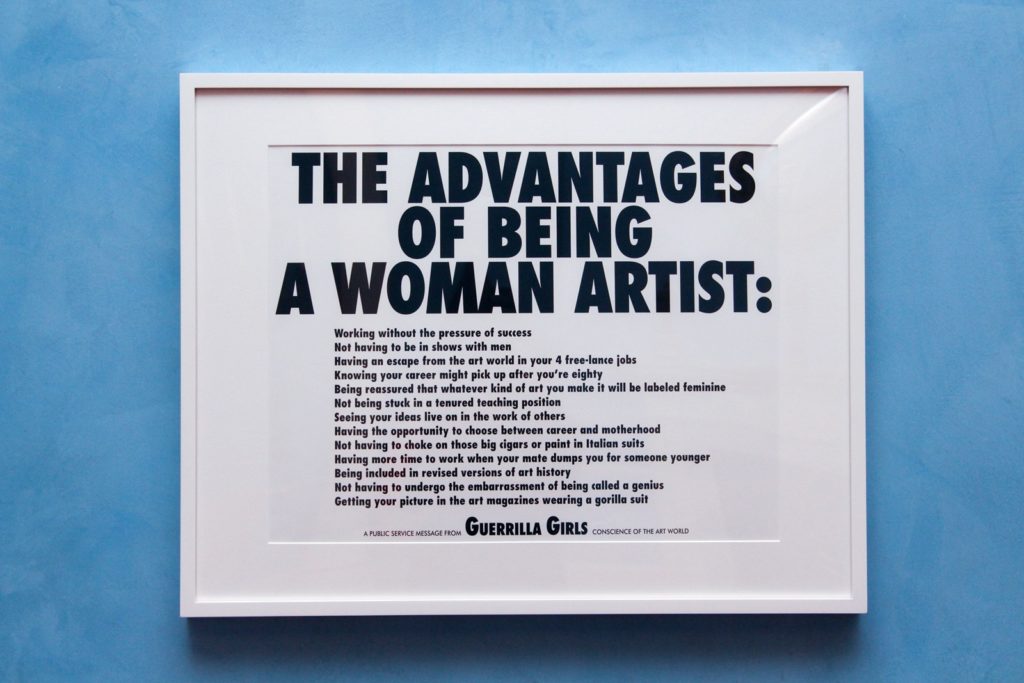

Guerilla Girls, The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1988). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

Good News and Bad News

Recent statistics are not all bad. Auction results show some progress on gender equity at the top of the market.

According to the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics, women artists’ percent share of total sales from 2019 to 2020 (year to date) increased from six percent to 10 percent by value, and from eight percent to 11 percent by volume of lots sold, at the New York and London evening sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips. Both figures qualify as the highest achieved during the preceding decade.

Of course, these numbers only show one slice of the industry. But the auction market is the part of the art business that is most male dominated, most visible to the general public, and historically most resistant to change.

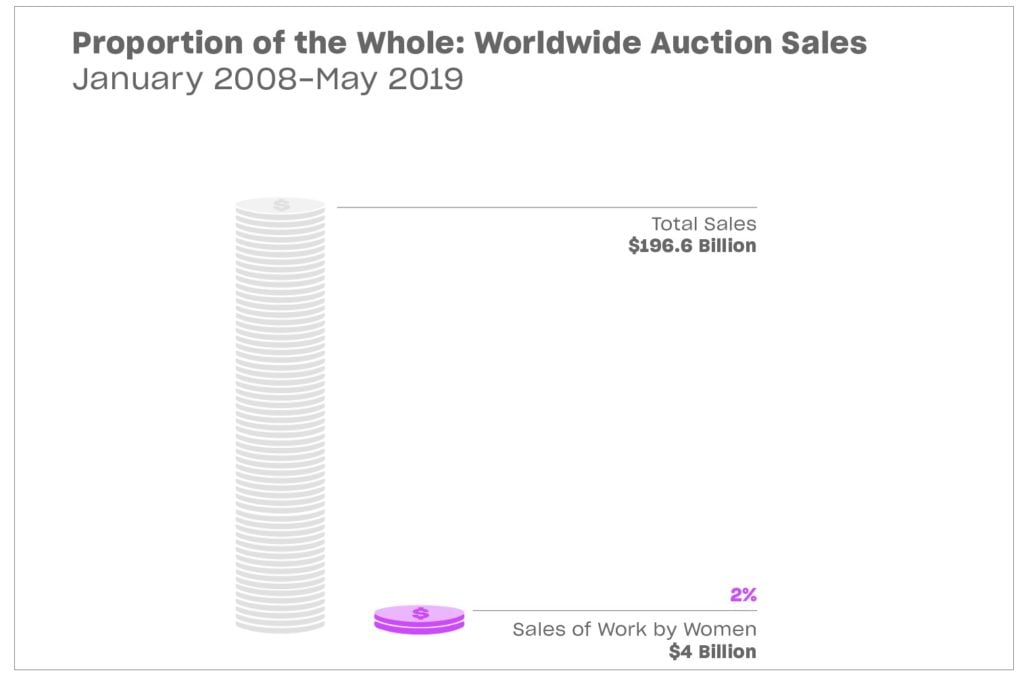

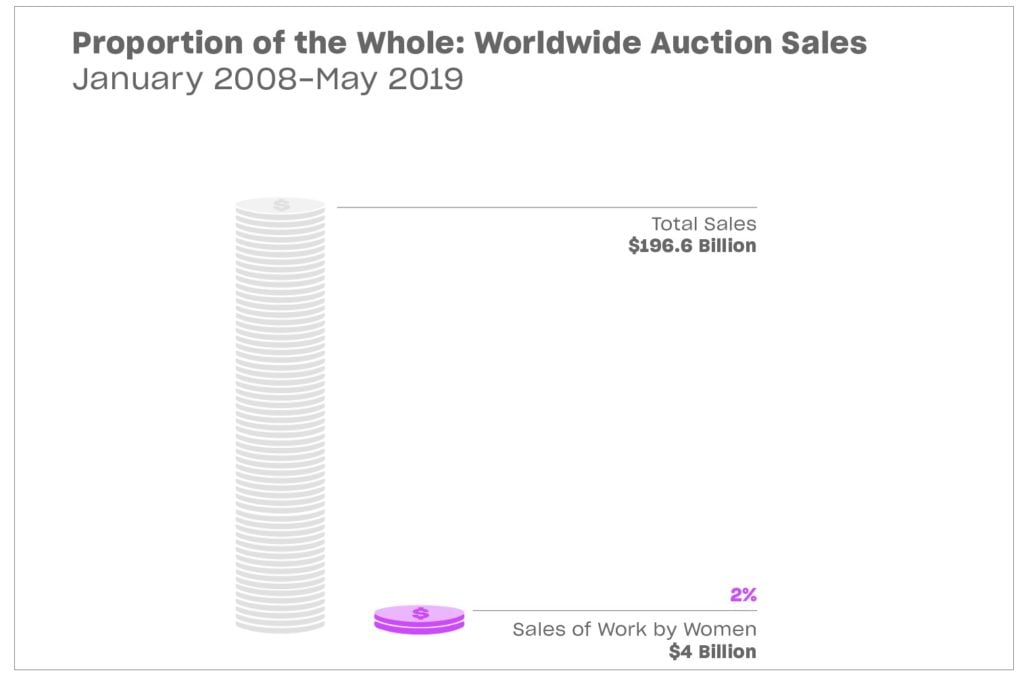

Courtesy of artnet News and In Other Words at Art Agency, Partners.

Some of the roots of this phenomenon originate beyond the art trade. There have been eerie parallels between recent hiring trends in the American executive ranks and recent buying trends in marquee evening sales.

According to Equilar, an analytics firm that examines corporate-leadership data, twice as many women were appointed CEO at the 500 largest US corporations by revenue in 2019 as in the prior year. Yet this improvement merely lifted the share of said companies featuring female CEOs to a paltry six percent.

The disparity lessens only modestly if we parse the apex of the net worth pyramid by gender. In 2020, only 56 women appeared on Forbes’s list of the 400 wealthiest Americans, comprising just 14 percent of the rankings—a nearly identical split between genders as the one seen on the list of 100 top-selling artists at auction in 2020’s first half.

Gender bias also continues to warp the more earthbound regions of the labor market. After analyzing the median earnings of full- and part-time US workers, the Pew Research Center found that women earned about 85 cents for every dollar earned by a man in 2018.

A staged photo of a boardroom in the 1930s. There’s a woman in the corner, over there on the left. Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images.

As in the art market, the gap opens even wider once race enters the picture. Women who identify as Black, Indigenous, or Hispanic/Latinx earned between 54 cents and 62 cents for every dollar earned by a white man in 2018, according to the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

What’s more, the overall gender pay gap “remained relatively stable over the past 15 years or so,” Pew reports. And data from the US Department of Labor this fall showed mothers of school-aged children have been pushed out of work at a disproportionately high rate during this year’s crisis, losing one-third more jobs than fathers and regaining employment more slowly—a development that could wreak long-term havoc on the road to gender parity in the labor force.

Women in the art world are facing the same headwinds. When you start the competition from behind and keep getting dragged back, it’s hard to catch up.

The Social Dilemma

While the private nature of the art trade makes it impossible for anyone outside the auction houses to quantify gender in the pool of bidders, anecdotal inquiries suggest this demographic tilts toward men.

Of nearly a dozen advisors polled by Artnet News in mid-October, seven said their auction clients skewed heavily male, while only one reported there was no gender imbalance. (Two advisors said their clients did not buy at auction enough to say.)

New York-based advisor Liz Parks notes that while she favors acquiring from galleries and works with more women than men, three-quarters of her collectors who do buy at auction are male—and 85 percent of the artists they bought at auction were male, too.

Why the disproportion? While it’s dangerous to propose innate psychological differences between the sexes, many of those interviewed suggested it may in part be driven by a combination of nature and nurture.

“The auction market has a huge dick-swinging component similar to investment banking wherein your desire to take on huge risk is continually stoked, along with your ego, and at least socially rewarded,” one art advisor says. “A lot of these men don’t know how to express value otherwise.”

Phillips Hong Kong saleroom. Image courtesy of Phillips.

While advisors suggested some male collectors derive satisfaction from staking claim to works that other people (particularly other men) perceive as valuable, female collectors interviewed by Artnet News articulated a different motivation: creating value where it did not exist before.

New York and Palm Beach-based collector Beth Rudin deWoody says she buys at auction only occasionally, because usually she “can find work early on, before it goes on the secondary market.” When she does buy at auction, it is because she has found “things that I want to get that other people aren’t interested in.”

Lee recalls visiting Louise Bourgeois’s studio for the first time in the mid-1990s and coming face to face with work spanning her entire career.

“These sculptures had been just sitting in her studio, and she was already established as an important artist,” Lee recalls. “Right there, I bought work from almost every decade of her output. Happily, her prices have skyrocketed since then, and it is a reminder that art by women is a wise investment.”

The Nurture Element

Women also tend not to be rewarded for risk-taking in the same way that men are. For example, a 2012 paper in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science found that, when stress levels rose, women took fewer risks than men—a phenomenon accompanied by significant differences in neurological activity.

Although there was nothing to suggest this split stemmed from inherent genetic differences between the sexes rather than learned behaviors, it could nonetheless contribute to a male-dominated pool of blue-chip auction bidders.

Gabriel Orozco’s Tracing Money, on view at Kurimanzutto’s booth at the Material Art Fair.

Nor have women—particularly younger women—been encouraged to take a front seat when it comes to their finances. A study published in June by the Swiss banking group UBS found that even the most educated and high-achieving millennial women were not as involved as their husbands in long-term financial decision-making.

In fact, millennial women—part of a generation thought to have pushed for open-mindedness about gender roles—exhibited less financial independence than Boomer women did. Among millennial women living with male partners, 54 percent said they deferred to their partners for long-term financial planning rather than sharing that responsibility or taking the lead themselves, compared with 39 percent of Boomer women, according to the study, which surveyed 1,320 women with at least $250,000 in investable assets.

The primary reason those women gave was a belief that their husbands knew more. These kinds of dynamics can also find their way into collecting patterns.

“Even if they are collecting as a couple, men still make a majority of the decisions when it comes to purchasing art, especially at higher price points,” Barbara Lee observes.

The Riddle in the Results

Still, breaking down auction sales by the two traditional sexes can be like trying to excavate fossils with a rusty shovel instead of fine brushes and tweezers.

Sara Friedlander, the deputy chairman of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s, estimates that 90 percent of her clients are either individual women or couples in which the woman drives the decision-making—even if she isn’t the one raising the paddle.

“It begs the question of how you define a collector: is it who’s writing the check?” Friedlander asks. “Is it the eye? Is it the passion or the pennies?”

Either way, she contends that the landscape of postwar and contemporary collecting has been shaped at least as much by female buyers and dealers as their male counterparts. Surely a canon without the influence of Peggy Guggenheim, Martha Jackson, and Ileana Sonnabend, among others, would look vastly different than any accepted today.

Ileanna Sonnabend at her gallery in Paris in 1965. Image courtesy of the Sonnabend Collection Foundation. ©SOCAN (2019).

Friedlander also cautions against comparing artists across eras and auction standing. For instance, women artists from the 1950s “have had decades of gender inequality [impacting] their market results,” whereas their contemporary counterparts have benefited from at least somewhat more enlightened thinking about gender. This means, for instance, that a living female star like Cecily Brown will perform better among her peers of all genders than a long-undervalued predecessor like Grace Hartigan.

Availability plays a powerful role in shaping auction results for blue-chip women artists, too. It’s difficult to convince collectors to part with premier lots of any kind. It’s herculean labor to do so in the uncertainty of lockdown. Factor in a consensus that the market’s appetite for works by great women artists is only growing, and the aficionados who currently own them have little incentive (short of experiencing financial distress of their own) to sell now, leading to fewer top-tier auction performances by women.

Shifting the Narrative

Meanwhile, some female collectors are opting out of the market conversation entirely and choosing to build value within institutions, where they feel their investment can have a more enduring impact.

Estrellita Brodsky, for example, has not only bought art by figures outside the Western canon for her own influential collection, but also funded curatorial positions in Latin American art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Tate, and the Museum of Modern Art as well as underwritten scholarships for students specializing in the field.

“Studying movements in greater depth, as opposed to merely auction records, allows you to have a better understanding of the value of certain works,” Brodsky, who considers herself an art historian first and a collector second, tells Artnet News.

“Most of my advocacy and philanthropic work stems from an interest in finding this interconnectedness, in emphasizing these stories and connections that remain overlooked by the dominant narrative, which is often dictated by a very New York and Eurocentric art market.”

Carlos Amorales, Why Fear the Future? on view at the Museum of Modern Art exhibition “New Perspectives in Latin American Art, 1930–2006,” curated by Estrellita Brodsky, in November 2007. (EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images)

While collectors like Brodsky are concerned with creating value outside the auction room, auction houses also have more pressing priorities than multiplying the number of women clients.

“When we think about cultivating collectors, we think about people who are passionate, people who are not afraid of taking certain risks in terms of the artists they’re buying and the financials [involved], and people who pay on time,” Friedlander relays.

All this means that, while the gender dynamics within the auction market are changing, they may depend most on the pace of change in the broader economy and the gallery-to-auction resale cycle. But no matter how long it takes for a major shift to materialize, the market as a whole is more aware than ever that one longstanding disparity should already be history.

“Who pulled out their stone tablet and wrote that male artists are better than female artists?” asks Parks. “Time to put away your chisel and step out of the Dark Ages.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.