The Gray Market

What the End of the iPod Reveals About the Art Industry’s Stodgy Market Model (and Other Insights)

Our columnist cycles through the iPod's history for lessons on why music and art have taken different routes in a digital era.

Our columnist cycles through the iPod's history for lessons on why music and art have taken different routes in a digital era.

Tim Schneider

This week, a reminder that technology is rarely, if ever, enough on its own…

This May, three weeks of high-level art-market events in New York have reinforced the trade’s strong, continuing default toward actual, physical objects—which will surprise no one familiar with the industry. Yet it stands against a milestone in another market that went the opposite way: last week, Apple announced that it had sunset the iPod, the product that rallied fans, artists, and record labels to music’s digital revolution two decades ago—and proved just how many factors have to align to bring about a paradigm shift in an art form’s distribution and consumption.

Nothing better captures the iPod’s influence than the fact that it was originally intended as a Trojan horse. Multiple digital music players were already available on the market from other makers by the late 1990s; they just hadn’t done much to capture the public’s imagination, let alone its expendable income. Then a second-run Apple executive thought a better digital music player could turn the tide in a larger campaign, as tech writer Tripp Mickle explained:

Steve Jobs, who returned to Apple in 1997 after being pushed out more than a decade earlier, viewed the emerging category as an opportunity for giving Apple’s legacy computer business modern appeal… Mr. Jobs thought tapping into people’s love of music would help persuade them to switch to Macintoshes from Microsoft-powered personal computers, which had a more than 90 percent market share.

By this standard, the initial return on Jobs’s gambit was mediocre. In the year following the product’s 2001 debut, consumers bought fewer than 400,000 of the original iPod model, which held about 1,000 songs and had about the same dimensions as a deck of playing cards, per Macworld.

Sales didn’t hit escape velocity until Apple’s 2004–05 fiscal year, when the company moved 22.5 million iPods. Annual sales then stayed north of that figure for eight consecutive years. They peaked at around 55 million units in 2007–08, eventually landing at about three million last year, per Silicon Valley venture-capital firm Loup Ventures. (Apple stopped publicly reporting iPod sales in 2015.)

In sum, the iPod product line is being retired after selling around 450 million total devices in 20 years. Its legacy in reshaping both Apple and the music industry is secure (for better or worse). But the iPod needed outside help to make its seismic impact, which makes it a useful model for grasping why digital files have been far less able to displace physical objects in the art trade.

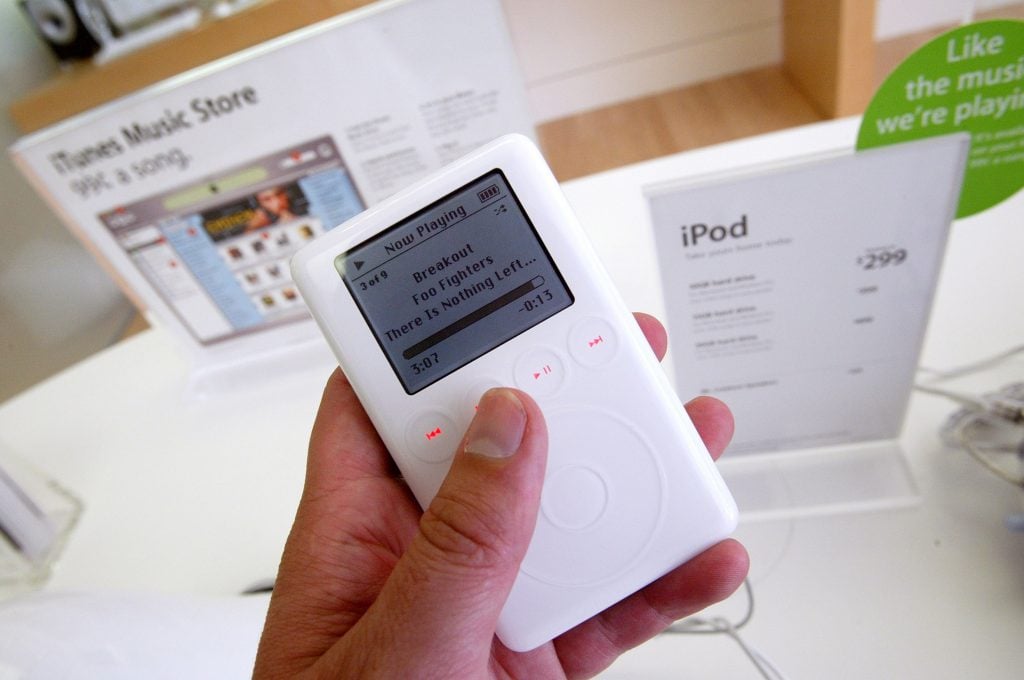

A 2003 model of the iPod, the game-changing product line that Apple retired in 2022. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

To me, the most important aspect of the iPod’s success was the state of competition in the music industry in the mid-aughts. Neither the iPod nor Apple had the power to push the culture into a digital-first age on their own. Instead, they needed the buy-in of music’s most powerful old guard distributors: the record labels. And the record labels only cooperated because they were already facing an even deadlier threat from elsewhere.

In 1999, a 19-year-old American hacker named Shawn Fanning launched Napster, a free program enabling unlimited peer-to-peer file-sharing among music lovers all over the world. The software’s value proposition hinged on the network effect; the more people joined, the more music they could share, and the more robust Napster’s library would become. Within a few months of its release, Napster offered access to practically any song or album users could think of, at no cost—which of course meant no royalties or licensing fees for labels or artists.

Once the scale of the problem became clear, the labels and their allies tried to nuke online piracy by suing Napster and even individual users of the software, alleging injuries ranging from copyright infringement to racketeering. But music journalist Steve Knopper, author of Appetite for Self-Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age, described the strategy as “a costly error. None of these defenses worked, and record executives spent four or five crucial years losing serious business to Napster before Steve Jobs came along with the iTunes Store.”

The story has a few more layers than Knopper’s quote indicates. A judicial order took Napster offline in July 2001, and the combination of legal fees, millions of dollars in damages, and an unsuccessful pivot to paid subscriptions pushed the company into bankruptcy the following summer. (It was eventually liquidated, and its name and business were acquired in 2016 by boutique music-streaming service Rhapsody.)

However, less than five years of Napster served as both proof of concept and proof of the overwhelming demand for free, unlimited music sharing. Several new peer-to-peer services emerged to meet that demand, including Limewire, Kazaa, and Grokster. In the process, online piracy mutated into the record labels’ grinning hydra: they spent millions of dollars to lop the head off the snake, but each time, two more grew back in its place. Jobs even ratcheted up the pressure himself with a star-studded ad campaign highlighting how indispensable the new Macs’ CD drives would be to any music lover interested in becoming a home D.J., understanding that their playlists would almost undoubtedly be built off of file sharing.

This dilemma all but forced the labels to embrace Apple, the iPod, and its companion marketplace, the iTunes music store. At its April 2003 launch, the iTunes store offered around 200,000 songs from artists signed to what were then the Big Five U.S. record labels. (Consolidation in the industry has reduced them to the Big Three today.) Crucially, every song was priced at just 99 cents, a major concession that the labels only accepted as the lesser of two evils. “We folded because we had no leverage,” said Albhy Galuten, then an exec at Universal Music Group. “The easiest way to fight piracy was with convenience.”

Yet even convenience wasn’t enough on its own. The alliance only started to staunch the labels’ bleeding after Apple continued iterating on the iPod. In 2004, the company introduced the iPod Mini, a smaller device with as much storage space as the $399 genesis model—only with a $249 price tag. The ensuing fiscal year saw iPod sales hit hyperspeed, taking recorded music into a new epoch defined by digital sales and consumption.

The exact nature of digital sales and consumption have changed since then, with subscription-based and/or ad-supported streaming replacing discrete purchasing and ownership as fans’ default model. But the rise of Spotify, YouTube, and Apple Music (the streaming successor to the now-defunct iTunes store) have only strengthened the transition away from analog recordings that the iPod initiated.

Yoko Ono, Apple. (1966) Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Even this capsule history of the iPod clarifies that music fans didn’t decide to go digital at scale because of convenience, new technology, or even both in concert. The paradigm only shifted after all of the following fell into place:

None of the above has a clean equivalent in the art industry. Technology giants have produced devices meant to expand the audience for art-as-software, but they’ve barely made a murmur. Since most of the world’s visual artworks are physical objects, it’s impossible for tech-wielding thieves to steal them en masse and offer them at no cost to anyone who might want them. Born-digital artworks make up only a small fraction of total visual artistic output, and they exist completely outside the practices of many, if not most, of the industry’s most bankable stars. Their analog works don’t port over to digital distribution as seamlessly as a musician’s songs, which remain essentially the same whether played through grooved vinyl on a turntable or an audio file on a smartphone.

It’s also important to distinguish here between art consumption and art sales. More interactions with visual art now take place on the internet and social media than away from the keyboard, and this has been true for several years. But very few of those online interactions demand paying a fee (or even tolerating ads in the midst of the experience). The same can’t be said for streamed or downloaded music, almost all of which comes at the price of a user’s cash or attention.

Still, it would be too much to say that these differences make art sales immune to meaningful change at the hands of technology and other external forces. To take the obvious example, NFTs have incited more structural soul searching than any innovation in the industry since Instagram launched more than a decade ago. Their profit potential and functionality have resurrected important re-evaluations of the value of middlemen, the viability of artist resale royalties, the expansion of the traditional art audience, and more.

At the same time, qualitative and quantitative evidence still suggests that NFTs are only a tiny niche within the already-niche art market, and there is no telling how much appeal they will hold after the current crypto crash resolves. Based on deep-seated animus against tech itself, as well as the “us versus the world” attitude of crypto’s early adopters, I’m less convinced that we’re headed toward a neat, complete integration of NFTs and the art establishment; it’s more likely that NFTs will sustain a largely parallel market for digital collectibles, with only selective crossover to power players in the art establishment. Think of it more as an extension of the artist-branded goods space than as a fundamental revision to the sale of art.

If so, that would be a starkly different outcome than the digital revolution that the iPod fomented in the music industry. Seeing the device’s 21-year life end without a similar innovation emerging in the art market makes it all the more unlikely to me that one ever will, especially now that we know how much outside assistance was necessary to alter the course of music history.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: not every art form wants to dance to the same tune.