Collectors always say that buying art is central to their lives in some way or another. Marguerite Hoffman makes that idea visceral.

The Oklahoma-born investor, art historian, and philanthropist bought her first work of art at the age of 35, while living in Dallas and working at the Gerald Peters Gallery. At the time, she had no heat—but she needed the painting. When she married the late National Lampoon cofounder Robert Hoffman in 1994, her budget got larger (and larger still after Robert and his father sold their Coca-Cola bottling company for nine figures). While the price points rose, the priorities stayed the same: art took precedence over most other expenditures.

The couple made headlines in 2006 when they announced plans to bequeath their contemporary collection to the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), where Marguerite had worked as director of marketing and public relations and later joined the board. The couple teamed up with friends and fellow collectors Deedie Rose and Cindy and Howard Rachofsky to pledge their holdings jointly. The haul was worth an estimated $300 million and stands to make the DMA a destination for contemporary art for generations to come.

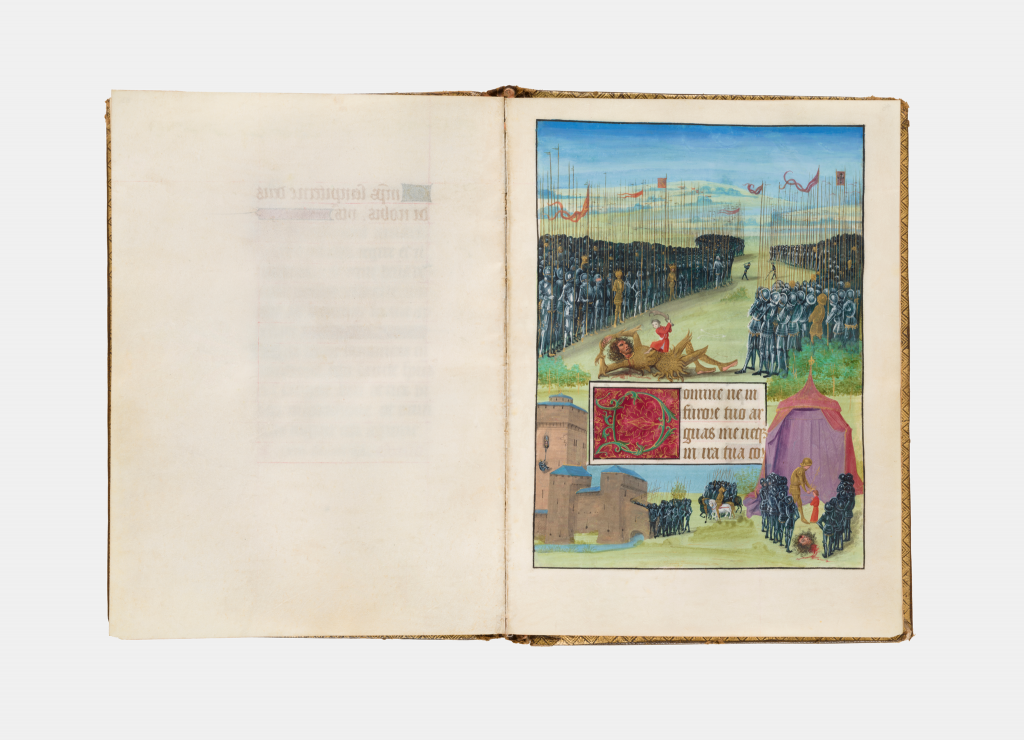

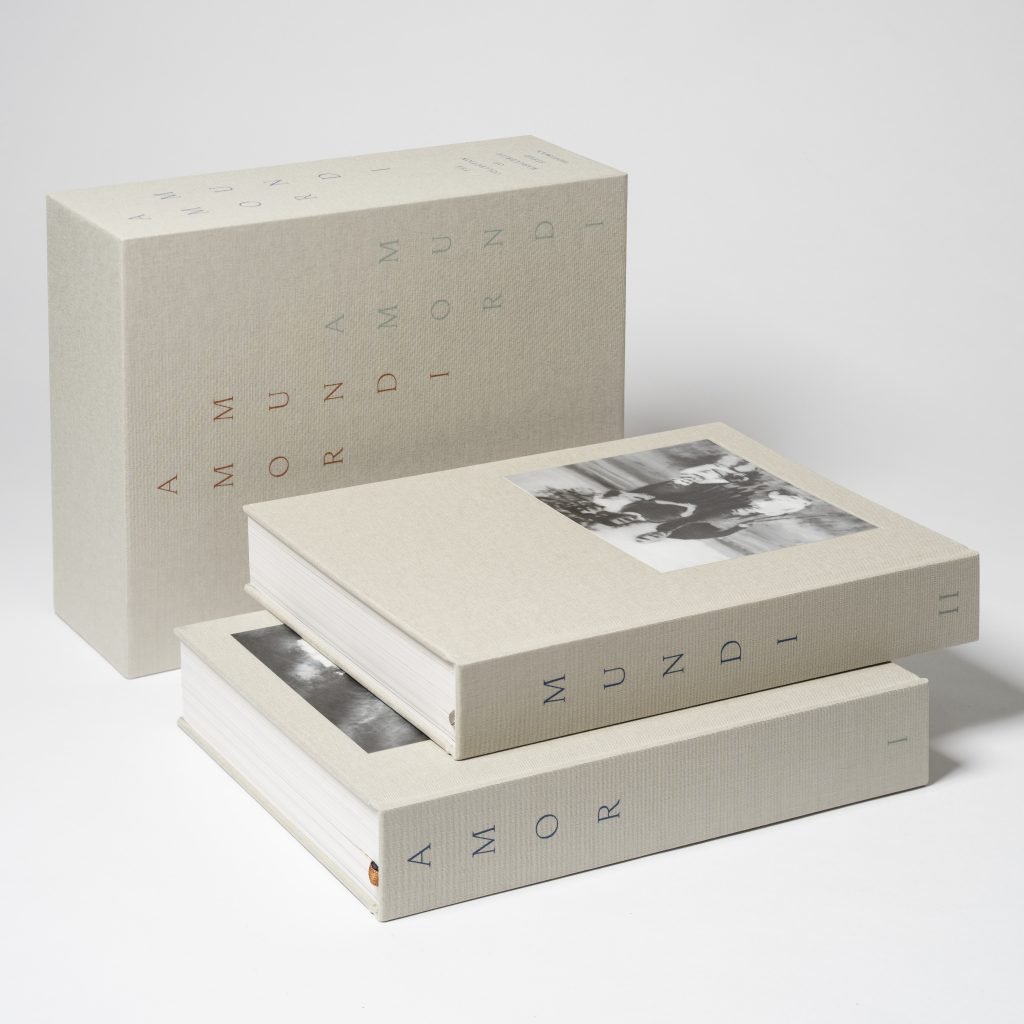

The year of the joint gift, everything changed for Hoffman when Robert died of leukemia. A pastime that defined their relationship became a solo pursuit. The process of collecting offered her a pathway through grief and an avenue for reinvention. This evolution is chronicled in a new two-volume publication dedicated to her collection, Amor Mundi, published by Ridinghouse in February.

Today, Hoffman’s holdings number some 900 works, from treasures she bought with Robert—like Philip Guston’s Studio Landscape (1975) and Jasper Johns’s Water Freezes (1961)—to those she acquired on her own, including examples by Maria Lassnig, Steve McQueen, and Renate Bertlmann, as well as illuminated manuscripts and antiquities.

On a recent sunny afternoon, I spoke with Hoffman over Zoom about the drive to possess, the sometimes-icky contemporary art world, and her favorite art experience of all time.

Amor Mundi: The Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman. Courtesy of Ridinghouse. Photo: Lewis Ronald.

I’m going to start at the beginning. Do you remember the first time you encountered a work of art as a young person that made an impression on you?

My deepest memories are of the Rembrandt self-portraits at the National Gallery [in Washington, D.C.]. There’s that whole room that takes him through the sweep of being very young, then very successful, and then he falls off the success ladder and ends up impoverished. That made a real impression on me. His intention to really capture himself in all those different moments and moods—I thought that was pretty courageous. And just the way he can paint. I would love right now just to stand with you in front of those pictures and look at the eyes and hands. There’s a person in there, and they’ve been through a lot.

Did you grow up with art?

No. Without disparaging my elders, it was just not part of our vocabulary. I grew up with a stag head on the wall and some prints—you know, maps of the world. So I was kind of tabula rasa, you know? They didn’t have to erase horrible visual memories of paintings of the seaside.

What did your parents do?

My mom was just a housewife and my father was an attorney. I was the first woman in our family to go to a four-year college.

After you graduated college, you took a trip to Europe and came back to get your Master’s in art history. When did you start collecting for yourself?

When I moved to Dallas in 1984, that’s when I started. I had no money. But even when it was bad, I would rather have one nice thing. I inherited my mom’s Steinway piano and so I always had a vase of flowers on that. I had no heat. I had a card table that I ate on. But I bought a painting.

You had a Steinway piano and no heat?

Yep.

That’s a very collector mentality—you aren’t necessarily thinking about the experience in the moment, but you have a longer, somewhat impractical view.

It was a really romantic kind of notion. I didn’t think of it like being in a garret in Paris or anything. But I was very clear about where I wanted resources to go. That may be the thread.

What’s the story of how you bought your first painting?

I went by the Eugene Binder Gallery in Dallas in the mid-’80s. He was the first real gallerist I knew. He had a gallery in Dallas and Cologne, and that was very forward for Dallas at that time. He was doing a show of a painter named Richard Shaffer. The painting was so beautiful, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. He had it right in his front gallery window. It was $5,000 and I thought it might as well be $5 million. But I needed that picture. I got up out of bed one night and I drove my car—the ugliest car on the planet, an Oldsmobile I inherited from my grandfather—and parked in front of the gallery and put my headlights on that painting. I thought, this painting will help me get—I don’t know. There was a lot of pain in my life. My mom was an alcoholic. I had just gotten a divorce from my first husband, an Episcopalian priest who turned out to be not such a nice guy. I moved to Dallas with him for this job he took and I thought, I never want to be back in this part of the country. And I thought, I need this painting to go with my piano and my flowers.

I went in to see Eugene Binder the next day and said, “I don’t have any money but I need this painting. I’ll pay you”—I don’t know what it was, $50 a month. And he looked at me and he said, “Why would I do that?” And I said, “Because I bet you have needed a painting before.” And he goes, “O.K.” It’s the only transaction I ever did with him, and that got me started.

Dana Schutz, Mountain Group (2018). © Dana Schutz. Photo: Jeff McLane.

What was it about that experience that hit you so hard?

Once you feel that—this sounds terrible, but that possession, that sense of ownership, that feeling that something has come into your life, perhaps for a reason, to confront you in some way you don’t even know how to articulate. It’s kind of unconscious. And so, you’re not even aware why you’re drawn to it. I’ve learned to pay attention to that sense. I think that’s the truest impulse. If I can stay true to that, I do O.K. It’s when I drift off of that, I’m not as sharp. But that’s it. That started the whole thing. I actually worked in a gallery and I collected some of the artists that we showed and I still collect those artists. But again, I got a discount, I could pay it off. It was always about the tradeoff between resources.

How did that change when you met Robert?

That continued when I met and married Robert because we had limited resources for a long time. Do you want a sofa or do you want a painting? These were real things for us. We thought we wanted a new house at one point because these three girls were growing up in this home and there wasn’t enough room for art and they felt like it was too precious. And then we saw a Twombly painting and could only do one thing.

There wasn’t even discussion about it. It was just—of course you’re going to buy the Twombly, that breathtaking thing that came out of whatever he was exploring in Rome in 1957. Everything else has to catch up if there’s room. To this day, there are few creature comforts that would supersede [art]. I don’t know why that is so powerful. I really don’t.

I think that in the way that some people are born artists, other people are born collectors. But it’s interesting to me that while you and Robert both had this drive to collect, you expressed it in really different ways. He was the planner and the guy who wrote down the list and carried it in his back pocket, and you were the one who moved on instinct. How did that push-pull play out in your time collecting together?

Well, it was an exact mirror of the rest of our life together. Robert had been married before and I’d been married before. We came together as adults. I think he didn’t realize, well, I’m marrying this feisty woman and she has a lot of opinions and ideas. I don’t think he realized that I was willing to go to the mat for those.

I’ll tell you just one funny story that summarizes it all. Robert had sold his company and he has some discretionary income and we go on a little bit of a buying spree. And at the same time, we’re building that gallery that’s in the backyard. When we finally opened it, there was so much potential. We’d been cramming everything in the house. Now we can do something incredible. And all I could think about was, my God, all the space we have for these things to breathe. All Robert could think about was, I want to see everything that’s been in storage forever. And it’s the first and only real fight we’d ever had about art. I thought, I’m not going to back down. He’s going to make this look ugly. I mean, he’s going to ruin it.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled III (1997). Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

So what did you do?

We ended up going to a therapist and we said, “We’re stuck.” And the therapist said, “Let’s make some ground rules.” First, Robert would give up the idea that art preparators charge by the hour and he would allow this exercise to take as long as it took. And second, when somebody said, “Let’s try it over there,” we would not be negative to the other person. And those two small things—let’s take time and let the art tell us where it wanted to be—resulted in a very different installation. It was a very quiet installation. But we were both, I think, deeply satisfied.

How were your philosophies different?

Robert had these rules: He only wanted to look at art by people who had worked for decades. He didn’t want to look at emerging artists. I don’t think he’d given himself permission yet to really become a collector because he was terrified about making the wrong choice. He was terrified about spending a lot of money making that choice. And because I wasn’t making the money, I was just like, “No, let’s go for it. In the worst case, we can go broke and we’ll sell it.” I think just giving him permission to lean into his desires, whereas maybe in another relationship that he might have had before—I have to be very careful here—it might not have been that elastic. So that was a beautiful thing.

It makes sense that the dynamics of a relationship play out in the dynamics of collecting.

We talked a lot about trying to live a congruent life, a life where what we said matched our actions. I don’t know another man who wanted to have that conversation at the level that we had it. We would take a yearly state-of-the-union walk for several hours and assess—where can we make more impact? Where can we have more fun? Where can we be better parents? I guess neither one of us wanted to settle very much. We wanted to push each other and ourselves. We had a lot of fun doing it, too.

I’m interested in how you found your voice as a solo collector after he died. It’s often easier to be the impulsive one when you have a counter weight. When that goes away, how do you trust yourself?

In retrospect, I can see the path. But when I was right in the middle of it, I felt exposed. We’d just made this big announcement [pledging our collection to the Dallas Museum of Art alongside two other major collections], and then Robert died. At the opening of the exhibition [of our collections] called “Fast Forward,” I wore black. I remember it perfectly. Here was this huge celebration of what could be in the future, and I was just barely making it to the podium. There was that sense of, is it just going to be this now, encased in amber, and I’m just the little widow? That idea made me really angry. I thought, I’m not doing that.

Making one determination really helped me move forward, which was: I will always try to honor what Robert and I did together and give him full credit for everything that he should get full credit for. In the book, if the credit line says, Collection of Marguerite and Robert Hoffman, that’s something we did together. If it’s just me, I leave off the credit line.

I had to figure out a lot of other stuff, too. It was a challenging time financially. It was a challenging time with a blended family that I didn’t know if I’d ever see again. The stepdaughters I’d raised. I mean, it was crazy. I would go to work in the morning at a vending-machine company that we had and then go to a board meeting. Robert made me promise on his death bed to stay chair of the Dallas Museum of Art.

I have a lot of grit that I had to learn growing up and I claimed that. I would go do whatever I had to do and then I’d get in my closet every night and cry. But only in my closet. It was kind of the same way with the art world. You had to give yourself permission to go back into the arena knowing it was going to be different, knowing people were going to be staring at you. And, you know, so much of this is about money. It’s about, well who had the money? Did she get it? I just thought, I’m not going to let this old-guy network beat me down and dismiss me because I know what I brought to the collection.

Cy Twombly, Gaeta Set IX (Gaeta Set 9), (1986) .©Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo:Jeff McLane.

The first year after Robert died, I was like, O.K., this is going to be the worst year of my life so let’s cram everything that’s going to be uber painful into this year and not let it dribble out. I went to Miami [Basel]. I went to Gagosian, which I never did business with really, and they had this suite of Cy Twombly paintings on paper. And I said, “I’ll take those.” I just wanted to have it done.

Then I had that epiphany when I went to TEFAF in Maastricht—there’s a world outside contemporary. I mean, the contemporary art world is scary, you know? I don’t know if you find it that way.

Oh, yeah.

And some of it’s distasteful. Boy, I’m really telling you stuff. But when I was on the debate team in high school, if you were against a team that was two guys, they always wanted to make the woman either a bitch or make her cry. And I thought of that all the time at first, being in the art world. I thought, O.K., you just can’t let them get to you. But I would get sweaty and it was hard. Especially going alone without any kind of advisor, which I really didn’t want to do. That is a good model for other people, but for me, I thought, well, advisors get to do the fun part.

I kept thinking, if I can just stay present long enough, there will be a light someday and everything won’t be so dark and I’ll feel better. And then look, I’ll have some nice things, too.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about that, because from what I know about your collecting at the time, there are these two parallel roads. You’re describing going back into the center ring of the contemporary art world. But at the same time, you’re exploring things that you never did with Robert, like collecting medieval manuscripts. I think that was also around the time you commissioned that project from Ragnar Kjartansson. Can you tell us about that?

I met Ragnar for the first time during the Venice Biennale, when he was doing the Icelandic Pavilion, this durational thing where he paints his friend every day in a Speedo bathing suit. His whole family is there cooking. It felt like such a cocoon, such a safe place of warmth and hospitality and creativity. And I just wanted to hang around him. So I would bike there almost every day. I think he probably thought I was some loon.

I remained good friends with Roland Augustine and Lawrence [Luhring], who represented him. We got together when I was in New York. And we were talking one night and I said, “You know what the dreariest part of my life is? Opening the mail. I hate opening the mail. It’s either a bill or somebody’s asking for money. Nobody’s writing you a love letter anymore. Nobody’s telling you anything new about themselves or asking how you are.” And Ragnar really needed some money. I had seen that he’d already done some of these watercolor postcards for Lawrence and Roland. I said, “I want one.” The commission was really interesting. I said, “What if I commissioned you to send me postcards—you can send me one, or you can send me 365, it’s up to you.”

Did you decide on the price before or after you decided how many?

Before. I started running home to see what the mail was. He was so open and shared with me so many things in those postcards—little phrases and heartbreaking or hysterical images. He told me about his divorce, when his baby was born, when he fell in love again. I thought, I don’t really even know you. And yet, it was such an intimate correspondence—it’s still my favorite art experience of all time. I cried when it was over.

So he did one every day?

Almost—I think there are 300 and something. I’d tell the gallery these are the most precious things. I think he knows it. And I’ve gone on to collect almost every one of his media pieces even though I can’t show them.

![Ragnar Kjartansson, Correspondence (2010-11), [detail]. Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2022/06/IMG_5309-1024x797.jpg)

Ragnar Kjartansson, Correspondence (2010–11), [detail]. Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

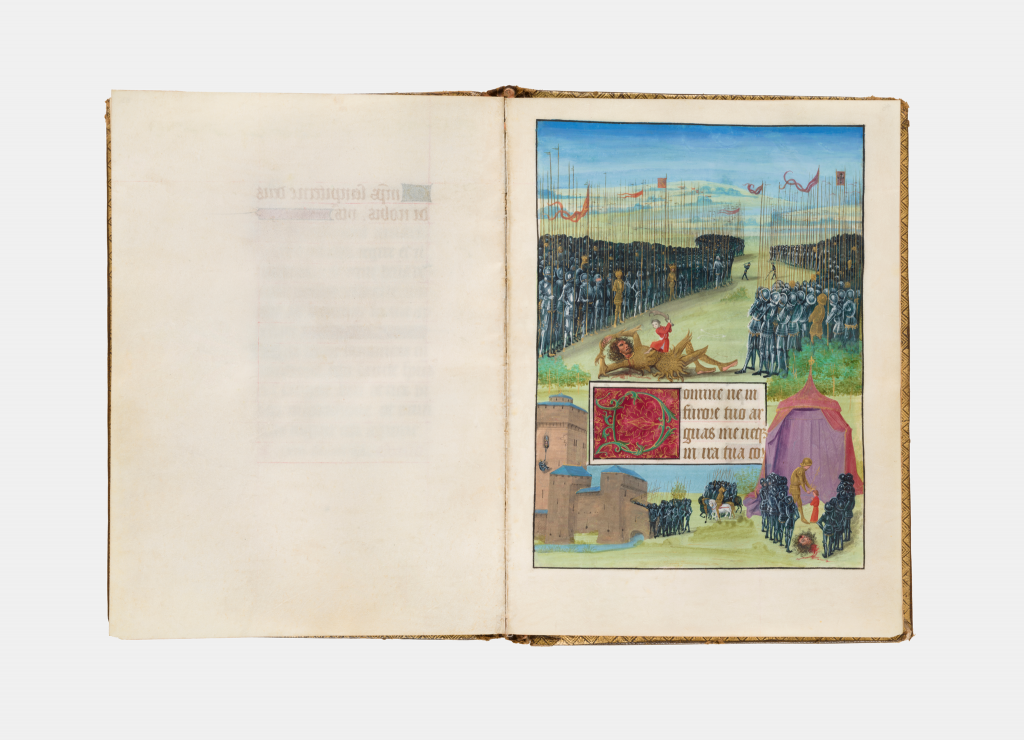

Yes. I go to Maastricht and I see this stand that has just hundreds of Books of Hours and other illuminated works. And I go in there and nobody talks to me. Finally, this nice woman comes over to say, “Would you like to hold one?” That’s when the dam burst. This was the key: I’d been in there two hours and hadn’t asked the price of anything. They were testing me. Because they said that Americans are so crass. That they always just want to find out the price and they don’t even want to look.

And so, that first hurdle, I was dumb enough to jump over, not consciously. I think because of all these things we’ve talked about that had been the French braid of my life, I was ready for that experience.

What drew you to them?

I could never imagine the privilege of flipping through one. And I never would have imagined how diverse they could be with the same rubrics and pretty limited iconography available. I also love the team thing: you had the person who made the parchment, the person who ruled the papers, the scribe, the master illuminator, and the studio doing the borders. Patrons were also very important at that moment because they could afford to commission these books. So you have to journey through history, European history as well as art history.

How large is the collection of manuscripts now?

I think it’s 23 books. But here’s where it gets really juicy. It’s been maybe five years since I’ve been back to see [manuscript dealer] Heribert Tenschert because it takes me so long to pay them out. My last acquisition from him was the prayer book of Catherine of Aragon. So, at that time, I’m watching The White Princess [a miniseries on Catherine’s life]. You’re seeing this fictionalized account of this historic woman’s life. And then I’m holding her f’ing prayer book. It was from a tough moment in her life between two marriages and I could still cry about it. I don’t know if she believed in God. I have no idea what her spiritual life was like. But they still needed something. Something to guide them.

Maybe art is a way of helping me interpret life’s meaning and helping me to ask the right questions. But it also will help me let go of life. You know, life and death are really big things for me. And it creeps people out and they don’t want to talk about it.

Book of Hours, Master of the Burgundian Prelates, Burgundy, (ca. 1480/90). Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

In a way, that leads me to the Dallas arrangement. Nobody wants to talk about death. No one wants to plan. It’s hard to even get people to write a will. And not only are you saying, “I’m not going to leave this thing I’ve spent all my resources on to my kids, I’m not going to sell it, I’m going to donate it.” But you are recognizing your own mortality in a way that I think a lot of people aren’t comfortable with.

It bothered some older collectors. I know it did. We asked someone else to join us and she said, “Why would I do that? You’re so young, Marguerite, please rethink this. Your life can change so much.” Little did I know. But the way we wrote the agreement, just the technical aspects of it, made it doable: [We were pledging] whatever’s in our contemporary collection [after both of us have died]. And with our gift—I don’t know if this is true for the other two—they can sell it all if they want to.

I was going to ask if there were any limitations on what the museum can do.

It was really important to me, having worked at the museum and watched the museum tie itself in a pretzel knot to satisfy vainglorious collectors, not to buy into any of that. You can’t control it. It’s all illusory. We put so much of our balance sheet—you know, 80 percent or more—into art when there are all these other worthy causes that I hope I gave generously to. But I could have done so much more had I not been buying art. So it’s the only way I can even begin to balance that ledger.

I’ve called myself in the past a hedonistic do-gooder. We started out at the beginning talking about this wanting—this demon kind of desire to have these things, to live with them, to get their secrets. And the only way I can align myself with that process is knowing that they’re going to go out into the world and we don’t own them. They have lives of their own. I know that sounds kooky, but that’s the way I see it. And other people will make judgments and I’m glad I won’t be here because I would probably disagree with them. But they can.

I can’t imagine having anybody giving them a better gift, unless they gave them the dollar equivalent with no strings attached. And I don’t know any gift that’s ever been made like that.

I had wondered whether your attitude changed once you committed to doing this, because you are no longer buying just for you. I imagined you’d be thinking about what holes in the DMA collection need filling. But if you’re saying, “O.K., they can do what they want,” then you’re sort of released from that pressure.

I still think about, what does the museum need? I’ll buy a picture and I’ll get it home and I’ll think, “I can’t even get that in the gallery space, it’s so large. What were you thinking? Oh, I was thinking of the back wall in that gallery at the DMA.” There are things in the collection that I’ve grown to really love that I bought because I knew they filled a hole. Deedie [Rose, one of the collectors in the joint pledge] has all this Latin American art. I know she’s not buying this Lygia Clark, so I’m not competing. And, by the way, it relates to the [Ellsworth] Kelly from 1952 in that they were both in Paris. These connections maybe aren’t apparent to other people but to curators, they’ll go, “Oh, oh, isn’t that interesting.” So it’s a little private pleasure that I have.

Lygia Clark, Composição (Composition) (1953). Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

Do you coordinate with the other donors in the pledge?

We used to more than we do now. We bought the [Gerhard] Richter [Stadtbild Mü (1968)] together with the museum. Everybody either put in cash or lesser Richters to get that piece. Howard [Rachofsky] has since given his part to the museum. I retain my third—not because I don’t want to be generous, but because I want one-third of the time to be able to live with it. So we used to talk more about things like that. With [former DMA director] Jack Lane at one point, we even did a giant spreadsheet.

Oh, really?

It’s gone on a long time now, so the intensity of the conversation is different. It’s more diffuse, and that’s O.K. I’m not going to feel restricted by any arbitrary rules or obligations. I’m going to buy what resonates with me at this moment in my life.

Part of the exercise of Amor Mundi was really looking at the collection—to say, what the heck have I been doing? Private collectors don’t look at their collections very often. And what I realized was that it was very European male painting-centric in some ways. That stemmed from those painters Robert loved and I still love. Since Robert’s died, I’ve added a Jasper Johns, Twombly, Brice Marden, and Peter Doig. They’re male and they’re white and I’m sorry about that. But I’ve also taken a very hard look at the whole landscape. And, you know, it was easiest to start with women because I’m a woman. And I’ve certainly had a lot of doors closed to me, and in Texas it’s really, really hard. And so, I never thought I wasn’t buying women.

Mark Bradford, A Truly Rich Man is One Whose Children Run Into His Arms Even When His Hands are Empty (2008). Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.

I do a project with Charlotte Burns looking at collecting patterns in museums and it’s often the case that we think we are doing better than we are. It also happens with journalism. We try to make sure that we’re commissioning a certain proportion of writers of color and I always thought we were until I started keeping track and then I realized what I think is not what we’re doing. In our study, we found that 1.25 percent of the DMA’s acquisitions between 2008 and 2018 were of works by African American artists, and 16 percent between 2009 and 2019 were of works by women. Your mind can play tricks on you if you’re not really rigorous about holding yourself accountable.

What does it mean to be an engaged citizen these days? What does it mean to look for equitable goals? I’m working on projects where the language has changed, the players have changed, the sensitivities are real and appropriate, and I am on the outside and learning. And my three daughters have not always been the most patient teachers, but I am so grateful to them for calling me out on every microaggression.

I need to get busier. I need to be more focused. I’m never going to apologize for all those wonderful artists that are in the collection. But who else was out there that I didn’t know about? That’s been a real journey and a real eye-opener. My goal is to acquire artists who are making art from a genuine place that makes sense in this collection at this time. And to do it with integrity and not trying to make yourself seem like something you’re not is harder than it looks. Everybody wants a gold star now for being on the right side of all these issues. A lot of collections are changing, as they should.

But the question for me became: What is my responsibility as a private collector? I always thought, it’s private, it’s mine. But the collection is destined for a public space. And it should, perhaps, look like the public that might want access to it. And it maybe should look like the world in which it was created.

So, work a little harder, Marguerite, to understand what’s out there and available. That’s been a gift to myself. And I think that’s what—if I can be so bold—moves people about the collection. It doesn’t feel cookie-cutter. It feels like it’s got some really weird stuff in there.

Those are my goals. Whether I meet them or not, I can’t say. But those are the goalposts, and I’m very aware of them.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

![Ragnar Kjartansson, Correspondence (2010-11), [detail]. Courtesy of Marguerite Steed Hoffman.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2022/06/IMG_5309-1024x797.jpg)