It’s been striking to me to see how there are two camps of people in the lead up to the big, twin shows of Jasper Johns at the Whitney and the Philadelphia museums. There were people who were really excited and there were people who were very aggressively not excited.

For the record, I guess I leaned a little bit more towards the “not excited” camp. Johns is historically monumental but if I was honest I’d have to say that emotionally, I don’t connect. In my mind’s eye, the work looks fussy and drab, at once alien to my world and too familiar to get excited about seeing again.

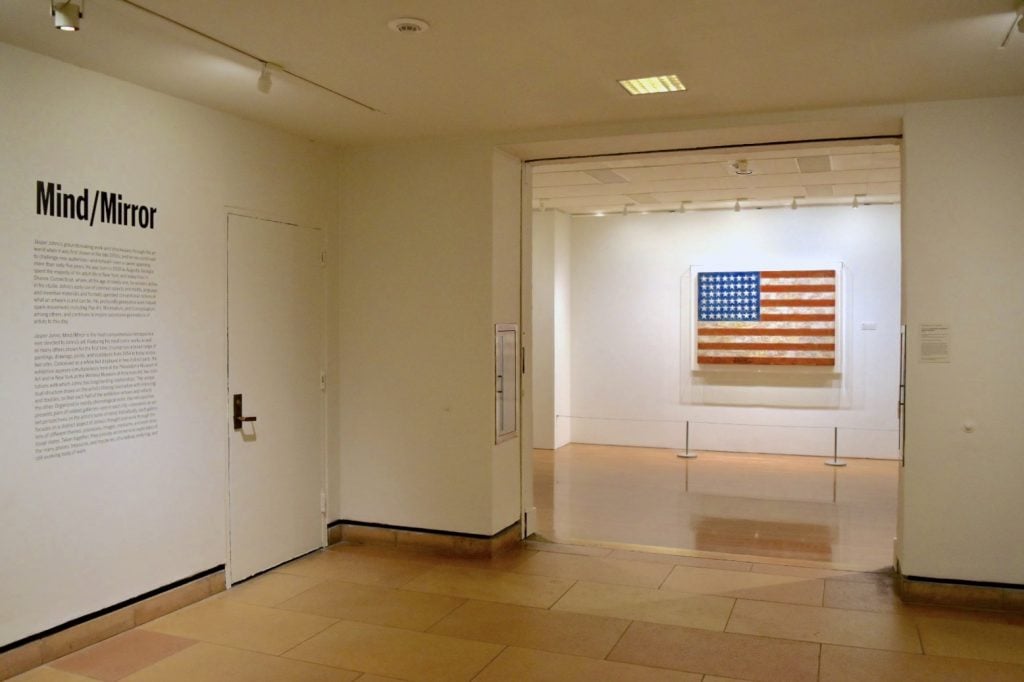

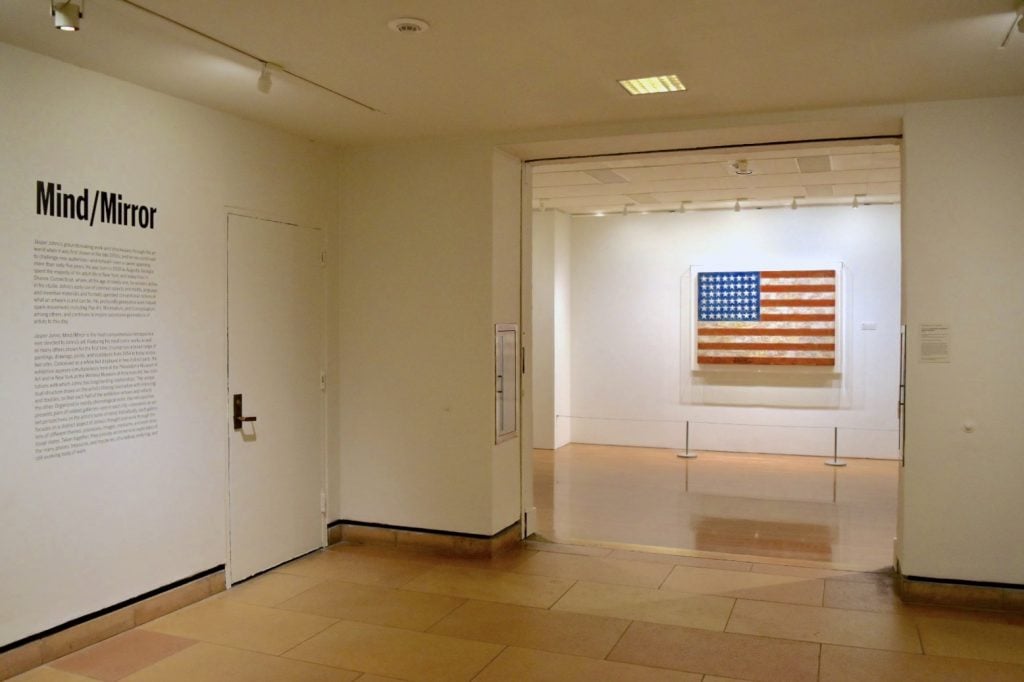

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” as the two interlinked museum shows are titled, does achieve something in that it makes me see this artist anew, up to a point. I still think that there is too much Johns here. Both shows would be twice as good trimmed by a third.

The two curators, Scott Rothkopf and Carlos Basualdo, are working very hard to make this vast spectacle land, and you can feel it. The accumulation of hundreds of works, often variations on a theme, is like listening to a greatest hits album and then listening to the remix album and an album of demos and alternative takes all in one sitting—and then doing it again the next day at another venue, if you are the kind of person who’s going to see both shows.

Installation view of the “Savarine Monotypes” gallery in “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Whitney Museum. Photo by Ben Davis.

But some of this effort is well spent, as with the PMA’s display of art from Johns’s personal collection from Japanese artists with whom he collaborated, mixed with his own works of the era. This gives a wonderful sense of creative dialogue and unexpected historical cross-pollination.

Installation view of a display of ephemera related to Jasper Johns’s time in Japan at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

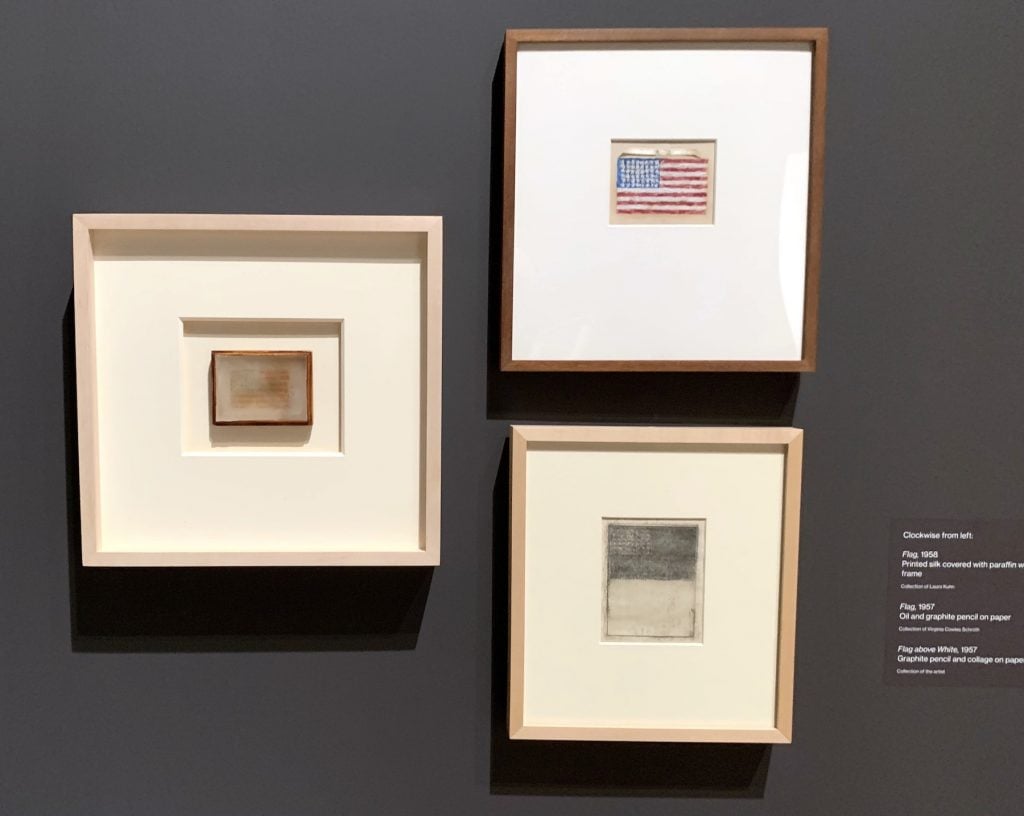

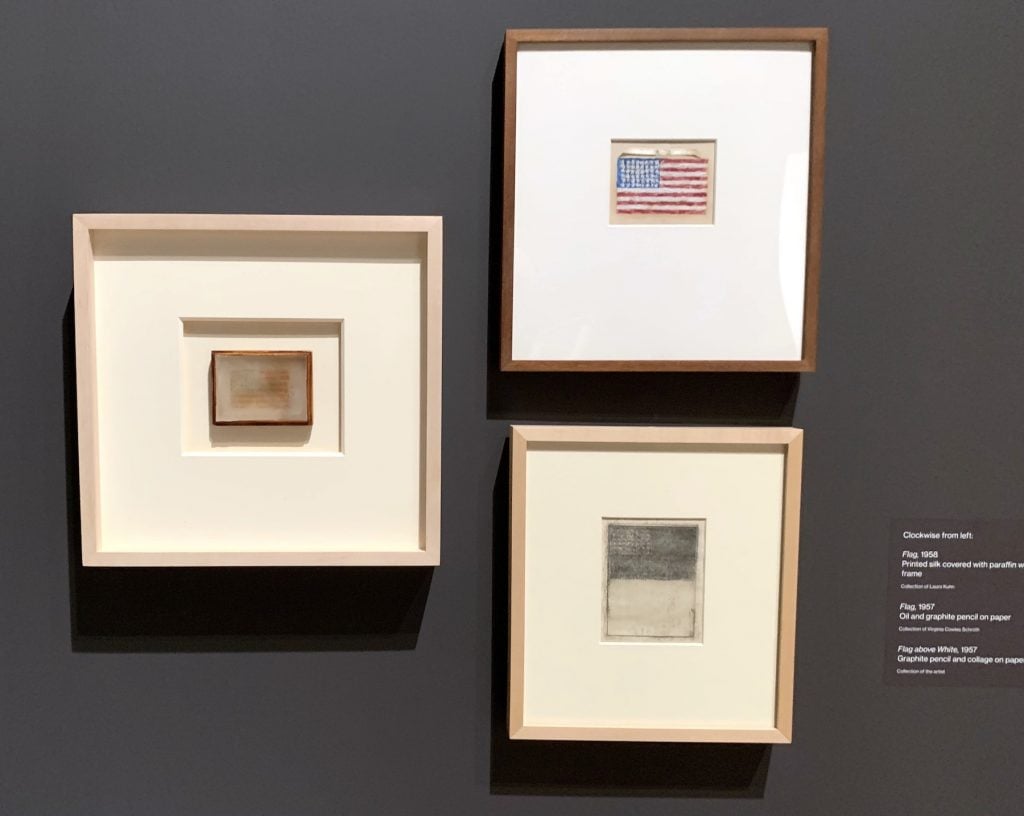

Or the gallery, at the Whitney, that assembles just very small Johns works, restoring a sense of animating intimacy to his familiar maps and targets and numbers.

Jasper Johns, Flag (1958), Flag (1957), and Flag Above White (1957) in the “Small” gallery at the Whitney. Photo by Ben Davis.

Anti-Narrative Painting

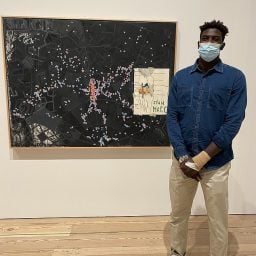

Curator Scott Rothkopf was frank about the challenge of surveying Johns now talking to Deborah Solomon in the New York Times, confirming my sense of a divided audience: “Older people may admire him and take for granted that he is among the greatest living artists, but I don’t think that’s necessarily true for younger viewers at the Whitney.”

The entrance to “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

A Jasper Johns exhibition is a hard sell in the contemporary environment for a particular reason. It’s not just that he is a White Male Artist Who Takes Up Space, being given a lot of space. Contemporary audiences are trained to read art through the lens of biographical narrative, particularly via a personal narrative of struggle. And Johns’s entire way of working completely goes against any sort of confession.

Rothkopf, who expressed the need to reframe the work for present sensibilities, puts a slightly greater emphasis on the personal, including on Johns’s experience as a gay man in a pre-Stonewall era. Put there is only so far you can go in this direction.

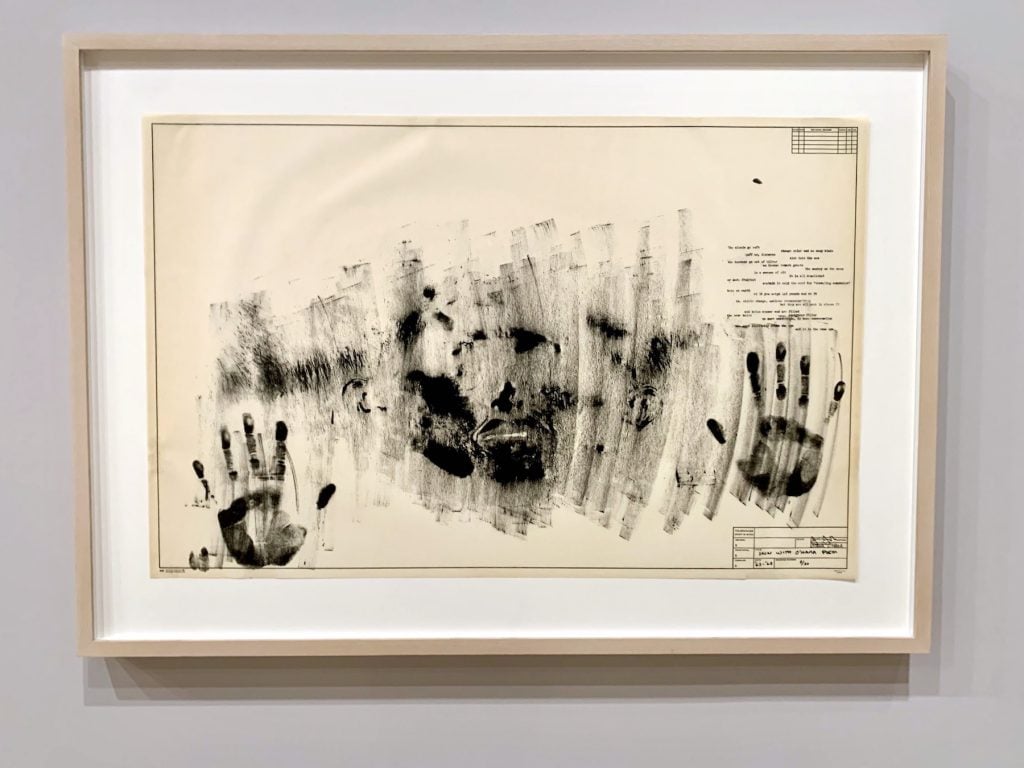

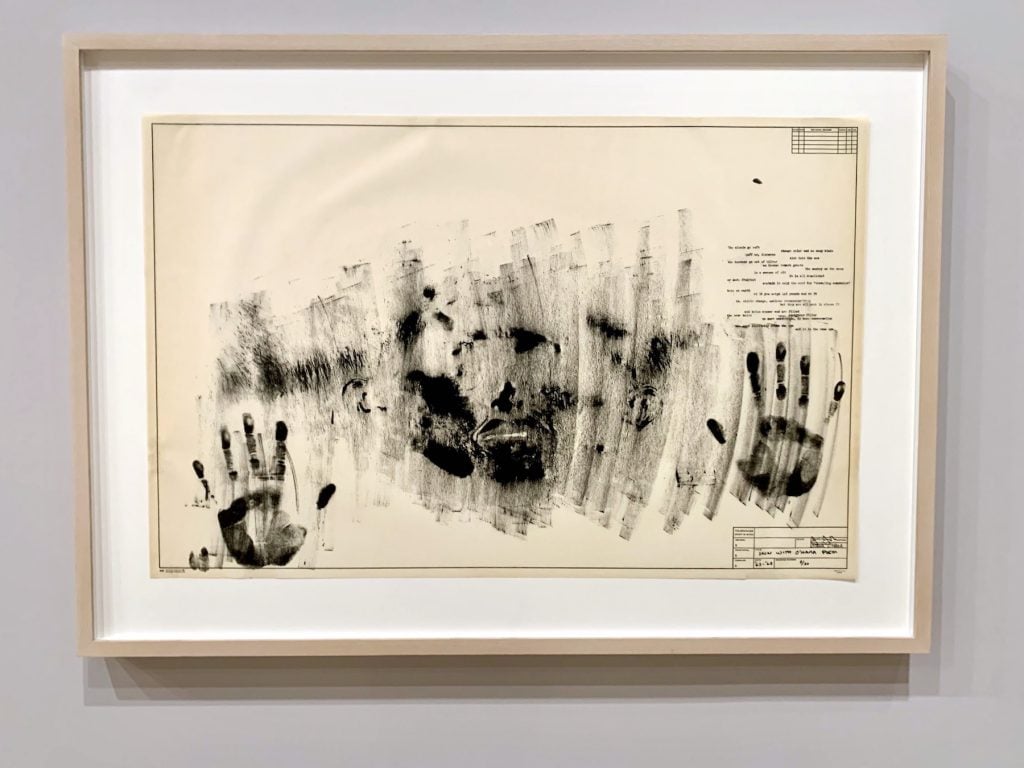

Jasper Johns, Skin with O’Hara Poem (1956). Photo by Ben Davis.

Jasper Johns’s famous romantic relationship with Robert Rauschenberg is alluded to and used to frame a number of early-‘60s works, made after their breakup. His affinity for the poet Frank O’Hara is stressed, with O’Hara described as a “curator and poet who wrote stirringly about everyday life and queer desire.”

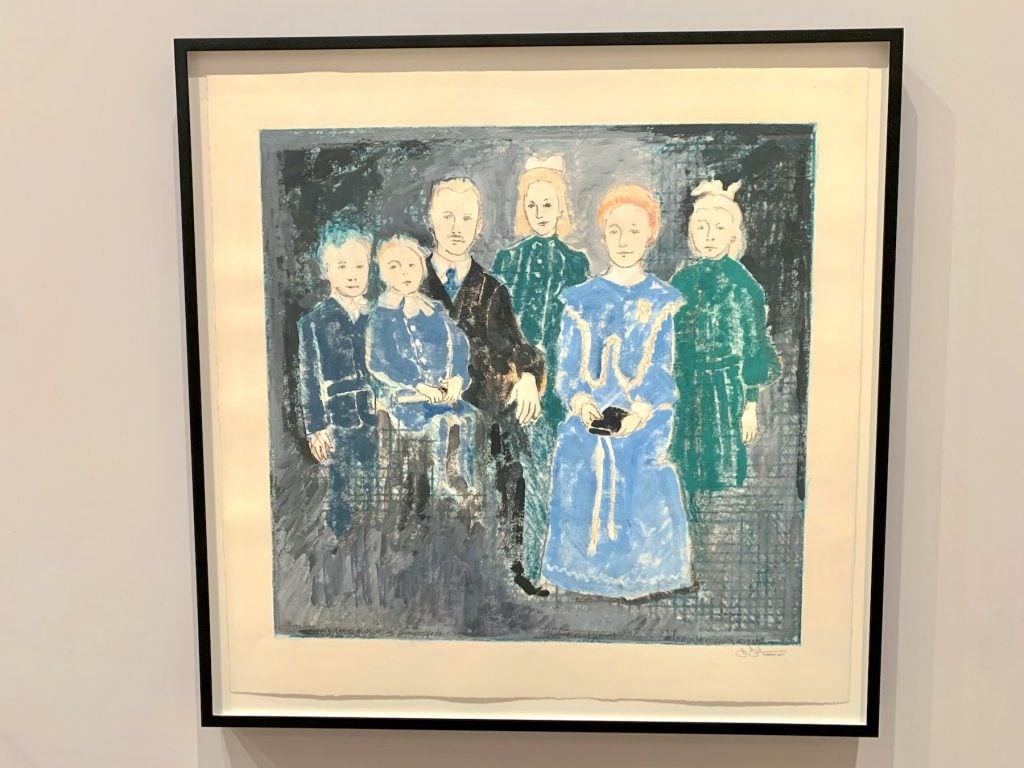

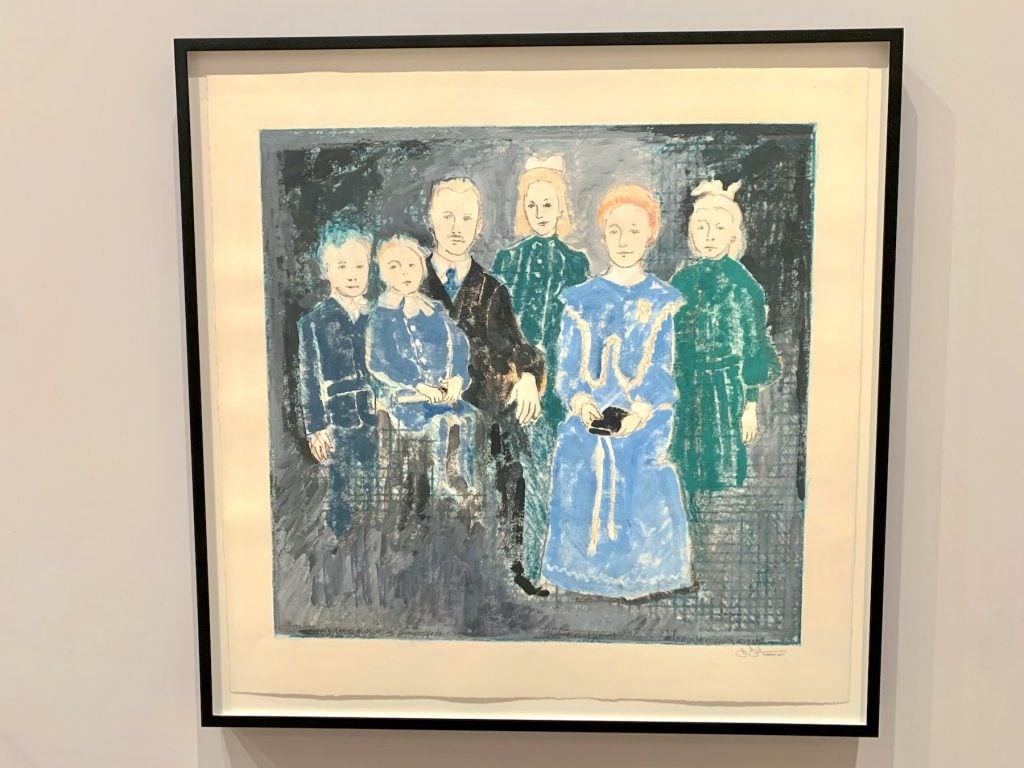

At his most autobiographical—say, in a ghostly, uncharacteristic 2011 image of a family photo—Jasper Johns is still speaking in whispers, not frank declarations.

Jasper Johns, Untitled (2011) in “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Whitney Museum. Photo by Ben Davis.

You may have heard the critical readings finding allusions to gay identity in Johns’s gnomic motifs: targets, bodily fragments, a paired spoon and fork, pairs of balls embedded in the canvas. But this subtextual queerness has a very unique combination of bluntness and indirection that, as Jonathan Katz suggests, takes you back to the days when being gay was signaled in very subtle sartorial and gestural hints. It does not really connect with the present out-and-proud language of desire and identity at all.

Abstract, But Expressionless

As is well known, Johns, along with Rauschenberg, the composer John Cage, and the choreographer Merce Cunningham, occupy a very specific historical inflection point in U.S. art. Riffing off of one another in their different creative niches, they created a cool, media-savvy, head-trip art that set the table for both Pop and Conceptualism in its turn away from the brands of abstract art that dominated the U.S. art scene, post-WWII, towards incorporating a variety of non-art materials.

Entry to “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

In Johns’s case, this came via experiments imaging things “already seen,” subjects so familiar that presenting them as art had a kind of attention-grabbing, counter-intuitive charge: paintings of maps and flags, sculptures of flashlights and lightbulbs.

But what strikes me in seeing so much Johns deposited here is not what he shares with Pop but what he shares with the earlier, antediluvian high art mythology—what makes him seem today like the product of an earlier era in the way that, say, Warhol or even Rauschenberg do not.

Despite its public acclaim as a harbinger of the rise of postwar U.S. art, Abstract Expressionism remained a priestly and self-contained art. “A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer,” Mark Rothko once said. “It dies by the same token. It is, therefore, a risky and unfeeling act to send it out into the world.” Johns seems to share this way of thinking of art as a rarified, difficult discipline, running counter to Pop ingratiation.

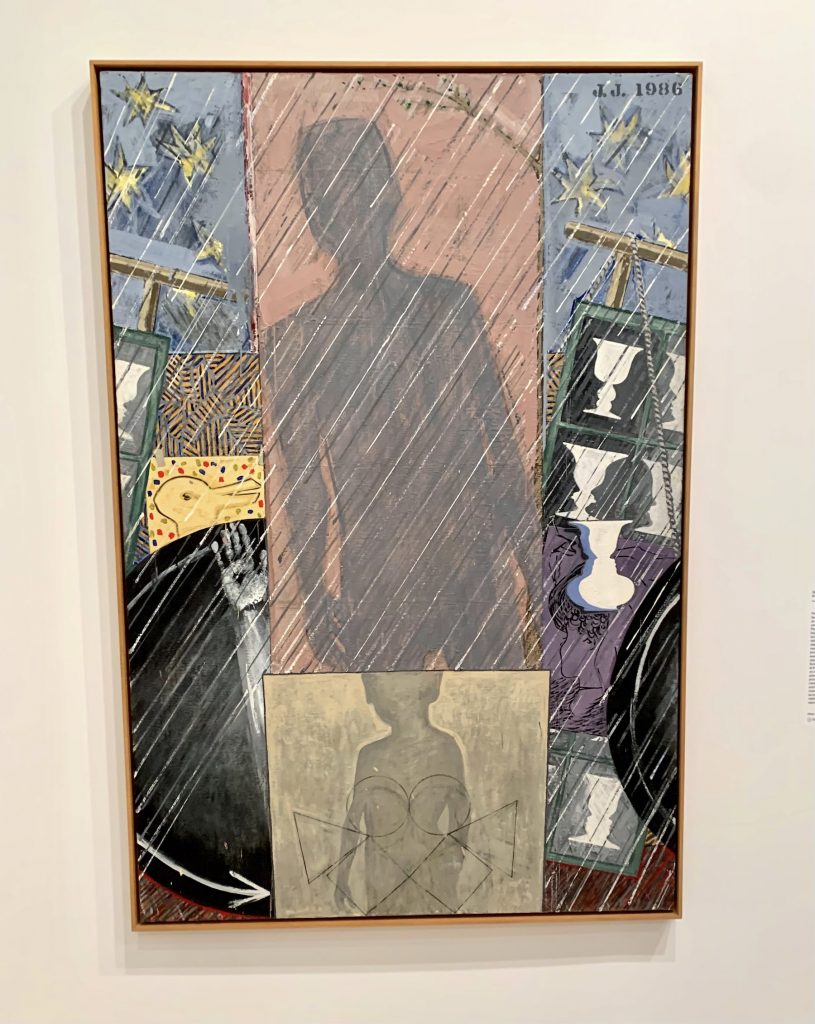

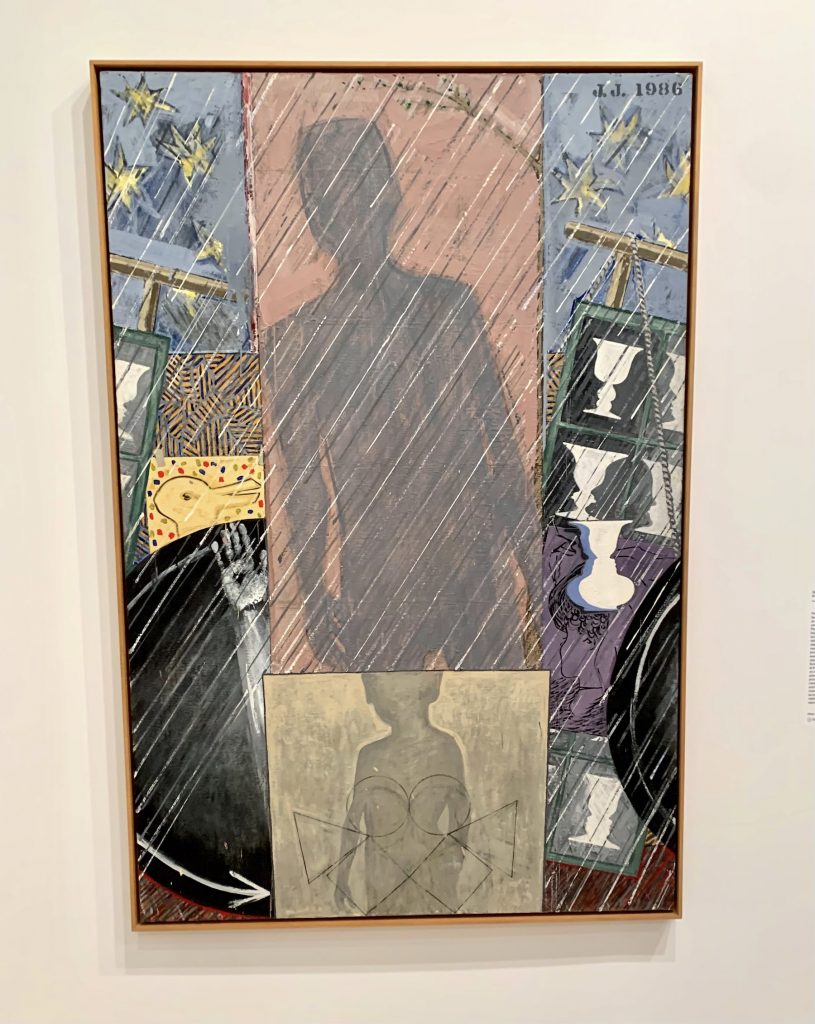

Jasper Johns, Spring (1986), from “The Seasons,” at the Whitney. Photo by Ben Davis.

Works like those in Johns’s mid-’80s series “The Seasons” (whose canvasses are divided evenly between the two institutions) seem to imply a viewer who learns to love the library of Johns’s private motifs the way someone might learn Sanskrit to read a mystical poem. Johns has for decades now made art that is defiantly, robustly hermetic, its public face the abstract surface of a thought that refuses to give up its final meaning.

Market Manipulation

In a counterintuitive way, this Olympian quality also connects to the transition point Jasper Johns represents for the history of the U.S. art industry.

Jasper Johns, Untitled (Leo Castelli) (1984) in the “Dreams” gallery. Photo by Ben Davis.

Johns was one of the first real art stars in the contemporary sense. The AbEx artists didn’t get famous, generally, until they were in their forties or later. Johns got famous young, and drew wondering headlines as the first artist to sell out a show of contemporary work, in 1958 at Leo Castelli gallery.

Castelli’s face recurs in various Johns paintings here, but the role that Johns’s early, miraculous gallery success plays in shaping his art going forward is best symbolized by Painted Bronze (1960), his deadpan, one-to-one bronze sculptures of two cans of Ballantine beer, a version of which features in both parts of “Mind/Mirror.” The idea for the artwork came from a line the painter Willem de Kooning said about Castelli: “you could give that son of a bitch two beer cans and he could sell them.”

Installation view of the “Doubles and Reflections” gallery at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

One can is a solid chunk of metal; the other, actually empty. This lends them a proto-Conceptual puzzle quality that was generative for many artists in their wake. But the context of that de Kooning quote suggests that Painted Bronze might also be read as being about the indifferent hunger of the ‘60s art market. Full or empty, real or simulation, deep meaning or marketing—the market flattens these nuances once it gets a hold of you, as it had then gotten hold of Jasper Johns.

Through sheer force of installational flair, “Mind/Mirror” improves my opinion of Johns’s post-‘60s works, which look good here, surveyed in rhyming series. Nevertheless, the common wisdom that a change came over Johns’s work in the middle of the 1960s, in the wake of his big success, and that his most ground-breaking work was before that, stands for me.

In the earlier period, his work is more concentrated, more provocative, and concerned with those “already seen” public symbols that remain his signatures. The flags and maps and the numbers draw you in with their familiarity only to repel you with the odd coloring and textures. Later, his work becomes much less sparing, and tends more to resemble drifting constellations of puzzle-like personal motifs.

Installation view of the “Flags and Maps” gallery in “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Whitney. Photo by Ben Davis

On some level, it is as if Johns’s vast and historic success launched him into the air, depositing him there with all his symbols, slowly spinning and bumping into one another and never returning to earth. And yet, contradictorily, it is this early and enduring commercial success that meant that his work was able to preserve, as if in amber, the older, high-minded sense of art—even as the lessons contemporary artists took from it went in exactly the other direction in the Warholian ‘60s.

Introvert-ism

And that brings me to a possible contemporary resonance of this Jasper Johns extravaganza.

I have a theory that the most generative creative energy emerges from the meeting of introverts and extraverts. You need the latter to stay up to date and to introduce new ideas and figure out ways to communicate that resonate with wider layers of people; but you need the former to let ideas steep and develop, to pause long enough to figure out the kinds of as-yet-unknown dimensions of meaning that make particular scenes, or particular bodies of work, feel special and individual.

Prints from the Philadelphia Museum of Art on display in in-gallery storage as part of “Rolywholyover,” waiting to be selected and reconfigured. Photo by Ben Davis.

Johns feels like a quintessential introvert artist here. And yet, notably, his most famous ‘50s-‘60s golden period remains a testament to the meeting of the two energies. New ideas were seeping in through the scene all around him, from Rauschenberg, with whom he freely traded ideas; from Cage, whose philosophy of randomness the PMA celebrates with a (slightly gratuitous-feeling) experimental display where selections of Johns prints are rehung regularly according to a randomizing procedure; from Marcel Duchamp, an elder whom Johns and his clique revered, and whose ideas they were among the first to popularize. (Duchamp’s The Green Box, from Johns’s personal collection, is featured at the Whitney.)

Installation view of the “According to What” gallery in “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” at the Whitney, with a display of Marcel Duchamp’s The Green Box from the artist’s personal collection at left. Photo by Ben Davis.

In Johns’s later work, the sense of new ideas from the present drops away. His new motifs are much more idiosyncratic, often deliberately near-illegible fragments borrowed from art that have some mysterious, personal charge for him—really the opposite of things the broad public has “already seen.” It is almost like an experiment in how much one can draw out of a self-contained, semi-autonomous, and introverted artistic world.

When the Whitney, a few years ago, did their big Warhol show trying to recuperate the Pop art god’s late, hacky celebrity portraiture from the ’80s, they billed him as a prophet of the Instagram age. The later Jasper Johns has exactly the opposite character, and the opposite relationship to the contemporary media sphere. No one’s going to call it art for the Instagram age—not these dun-colored compositions which never settle down into a definitive form.

Installation view of Jasper Johns, The Bath (1988) and Montez Singing (1989). Photo by Ben Davis.

But then, for this very reason, I find that Jasper Johns’s murky introversion weirdly plays like a splash of contrasting color against the present hyper-pop moment. That’s how I’d make the case for him now.

Johns’s post-‘60s output may feel as if he has lost the animating balance of inward and outward energies, becoming a little aloof. But in the present, at a time that pushes culture so much towards extroversion and self-promotion, with constant incentives to resculpt one’s inner life around what plays well on the big stage, Johns’s tenacious inwardness feels like a reminder of a missing ingredient in the creative formula—from the other side.

Sex Among the Ruins

In the end, Jasper Johns is a serious artist, which means he doesn’t just paint for himself. The point of all that deep, silent deliberation is that against its background, every so often, something new can emerge that actually startles.

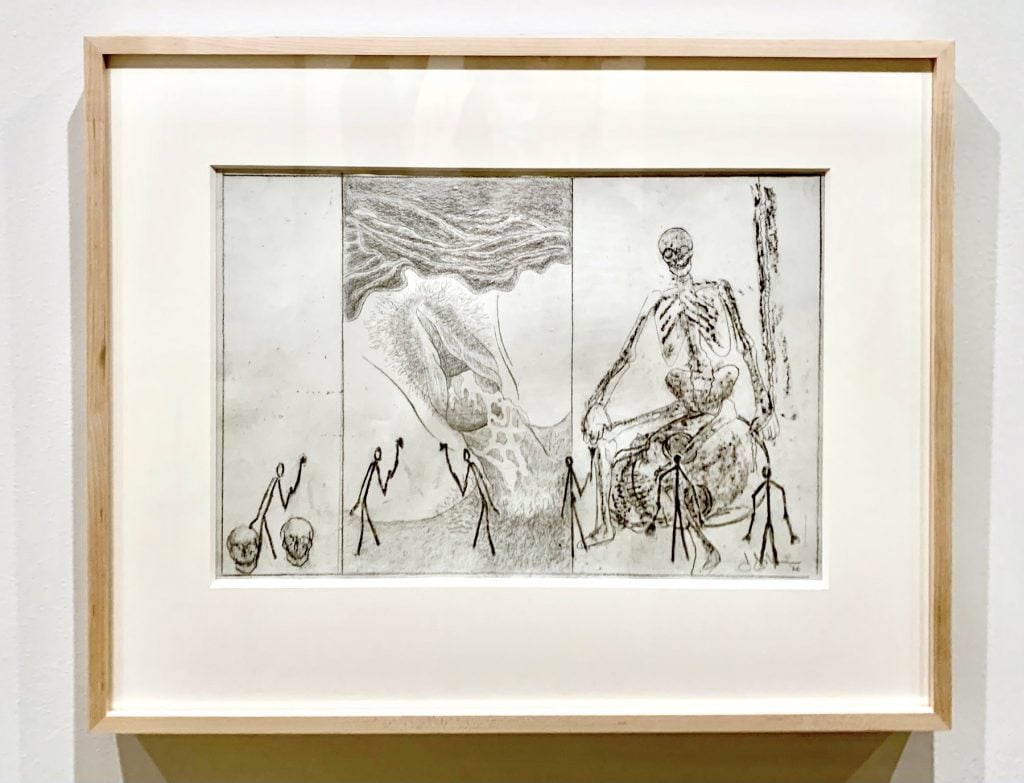

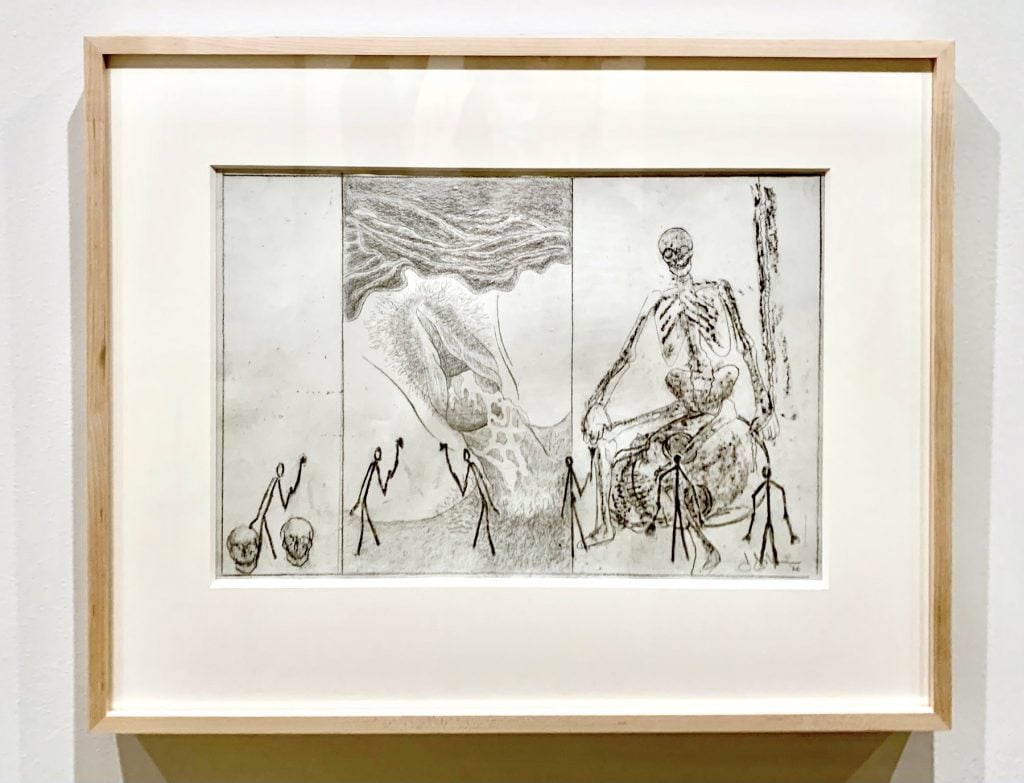

Finishing up the circuit of galleries in Philadelphia, I thought that I had Johns all figured out. The final galleries are infested with skeletons, suggesting thoughts of death—both actual death and the exhaustion of meaning. And then I came upon a small work from 2020, just last year.

It’s called 6 Artists at Work. It features skulls, and skeletons, and six small stick figures with paint brushes that have recurred in Johns’s work for years.

And at the center, looming over it all, there’s a fully pornographic image of a penis entering a vagina.

Jasper Johns, 6 Artists at Work (2020). Photo by Ben Davis.

Floored, I (bashfully) wrote Carlos Basualdo about it. He replied that it related to John’s longtime interest in Japanese erotic prints and possibly his “Tantra” series (though these are mostly abstract patterns), and that the new image also appears in drawings related to Slice, a large recent painting incorporating an astronomical map at the Whitney. (A just-opened drawing show dedicated to the “Slice” drawings at Matthew Marks, concurrent with “Mind/Mirror,” features the new pornographic motif, referring to it as being drawn from a “19th century Japanese Shunga print.”)

“The close up brings an entirely new dimension to the skeleton drawings and paintings,” Basualdo volunteered. “I was very keen on showing the work in the context of the last gallery because I believe it changes the tone of that final section of the show.” He’s right!

I don’t know exactly what to do with this image. My mind latches onto all kinds of interpretations, all of which feel over-thought in relation to the literally orgasmic imagery (It’s about creation! It’s about origins! It’s about deflecting reductive readings of his art based on sexuality! It’s about saying he doesn’t give a fuck—or that he does!).

There’s a kind of delight in seeing this 91-year-old artist introduce something that is such a swerve and yet so absolutely in keeping with his life-long capacity to confound. Into this career summation, without losing his characteristic auratic reserve, he’s snuck an image that is almost the definition of a provocation.

Mainly, the unexpected arrival just renders me speechless—which may actually be what Jasper Johns wanted from his interpreters all along.

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Philadelphia Museum of Art through February 13, 2022.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.