Opinion

After Scooping the World on ‘Salvator Mundi,’ Kenny Schachter Has More to Reveal About the Leonardo—and Art Basel’s Biggest Deals, Too

How can Kenny top his last column? Read on and find out.

How can Kenny top his last column? Read on and find out.

Perhaps you may have read (or heard) that I outed the whereabouts of Leonardo da Vinci’s Savator Mundi in my last column. It was the scoop heard around the world, from Australia to Zimbabwe, picked up by pretty much every major global news outlet as if it were something that actually mattered. Hope the Serene, the yacht where Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman is presently enjoying his latest acquisition, doesn’t become an Iranian target, like the Saudi oil tankers recently hit in the Gulf of Oman. Art Basel global director Marc Spiegler called me the art world’s Sherlock Holmes. I’ve been called (a lot) worse.

I was approached by a Middle Eastern man in front of the entrance to the fair in Switzerland last week who asked me, “Are you Kenny Schachter?” After I responded affirmatively, he said, “I’m from Saudi Arabia”—at which point the prominent collector I was previously chattering to recoiled in fear, literally jumping back three steps in one go. Thankfully, he only wanted to say he liked my writing.

My latest scoop is just as juicy: the guarantor of the Leonardo was billionaire Taiwanese investor Pierre Chen (born Chen Tai-ming), who in 1977 founded Yageo, a New Taipei City-based manufacturer of parts found in mobiles, automobiles, and desktops. Chen is the auction houses’ go-to-guarantor for big-ticket items, by far the world’s most successful player in that arena, and the canniest. He’s famous for not even bothering to see the art he places such gargantuan bets on in person—jpegs suffice. He’s that good, and that sure of himself. His touch is as platinum as the key component used in the hard drives and circuit boards he sells.

Meanwhile, one of his twin daughters, Jasmine, is a talented specialist at Sotheby’s (and an Olympic-level horse jumper) who curated an exhibition of George Condo and Picasso in Hong Kong. Her hire was a clever personnel move by the soon-to-be-private auction company, where her dad also guaranteed the SFMOMA-deaccessioned Rothko for $50 million in Sotheby’s last New York sale. (I’d gather Jasmine held shares in Sotheby’s at the time of privatization, so good for her.)

Though the 52-week high of Yageo shares is 1,310 New Taiwan dollars, it last closed at NT$261, near its low on the year of NT$247. So, it’s an especially fortuitous thing that his Leonardo guarantee, at $130 million, netted him a whopping payday of $135 million in pure profit, all with no money down! Which, as I previously reported, has been paid in full. So I asked Jasmine to pick up the tab for a dinner in Basel—I’m still waiting.

While I am at it, the underbidder of the Leonardo is said to be Liu Yiqian, the Chinese owner of the Long Museum. Before the auction, the painting had been offered to gallerist/art investor Adam Lindemann by the son of a restaurateur—never a reassuring sign—first for $50 million and then for a reduced rate of $47 million before finally being sold by Sotheby’s private-treaty division to freeport owner Yves Bouvier for $80 million. Immediately after, Bouvier flipped the painting to Russian Dmitry Rybolovlev for $127 million, not a bad return for a day’s (or two) work. With a hammer price of $400 million for Salvator Mundi, Rybolovlev might consider abandoning his flurry of lawsuits against Sotheby’s and Bouvier and return to his previous pastime of idle oligarch-ing.

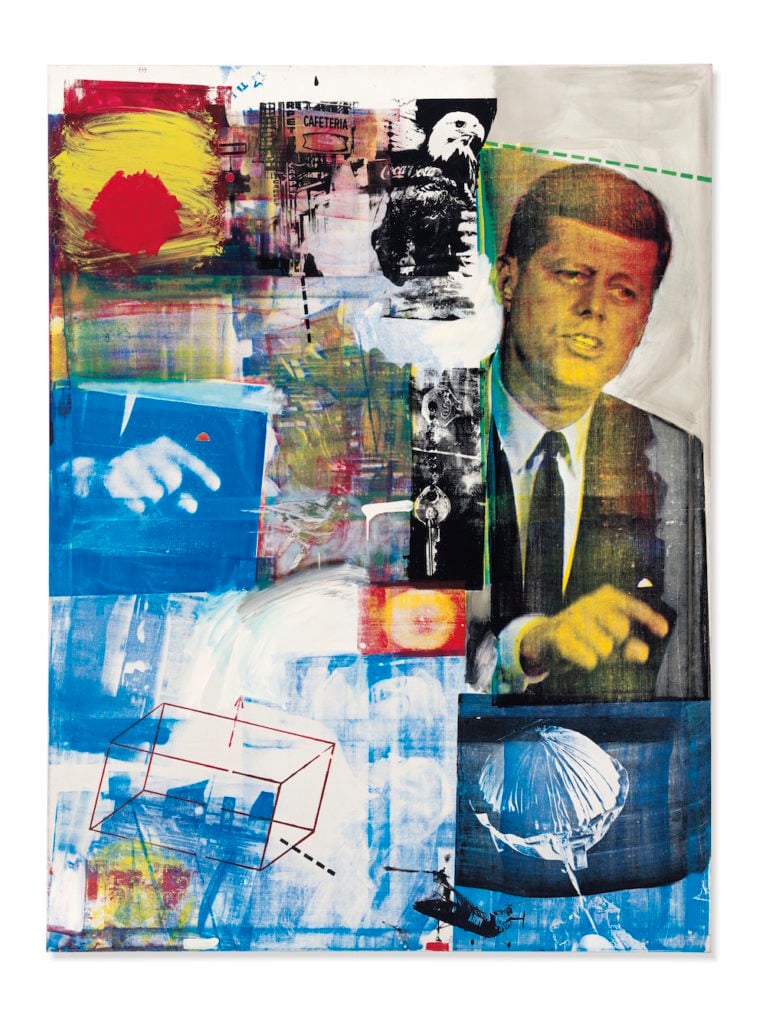

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II (1964). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

I’m as exhausted as you are at this point, but not done slinging dish on May’s auction results: billionaire Chicagoan Ken Griffin, founder of the Citadel hedge fund, was the buyer of Robert Rauschenberg’s Buffalo II (1964) for $89 million at Christie’s—not, as previously reported by others, Crystal Bridges’s owner Alice Walton. (A Citadel representative denied Griffin purchased the piece.) And gallerist Per Skarstedt snagged Christopher Wool’s Fool for nearly $15 million on a fat Sotheby’s credit line.

That’s not all: Idan Ofer, son of Israeli shipping magnate Sammy, was the underbidder on Koons’s bunny, while his brother Eyal picked up a Sigmar Polke owned by Nicolas Berggruen from David Zwirner at the Basel fair for about $8 million, though it was widely reported to have sold for $10 million. Okay, done… on the auction front.

Now, onto the forced march that is Art Basel, which held its 50th edition this year, slowly catching up to me in age. The fair is waiting to celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, one of the little deceptions of vanity that come with the accumulation of so many years. (Call me a 50th-anniversary truther, like Ted Loos.) No matter how desperately I wanted to skip—and I did—FOMO kicked in and off I went.

Anyway, I’d be remiss to miss the fair for the wealth of information wafting through its halls, let alone the multiple museums’ worth of art offerings. As one prominent New York dealer put it: “I anticipate a shit show with Brexit and Venice—and, of course, the prices keep going up.” After attending most of the Swiss iterations for the past 30 years, I can attest that ever escalating prices are the only difference I can discern over the preceding decades, with much else remaining exactly the same as it ever was. And I beg to differ with the naysayers, the art was as fabulous and wide-ranging as ever.

Subsisting on a diet of chips and chocolate (there’s no time for anything more substantial), I mustered the strength to fight the ruthless queue-cutters to get into the fair and taxi-line-dodgers to get out. According to the indefatigable doyenne of art dealers, Rhona Hoffman, pre-selling at the Basel fairs used to be prohibited—at 85 years young, she should know—but now it’s near impossible to find any sought-after primary works not snapped up before the gates open.

The human condition of art evolution. Illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Word in the aisles was that there were fewer prominent American and Chinese VIPs than last year, yet there were still plenty enough to fill the coffers of dealers—though success, as usual, took the shape of a bell curve. The reduced Chinese turnout, no doubt due to continued capital-outflow restrictions and the trade war, smarts especially due to their high-spending tendencies. (For instance, they account for the highest spending by tourists in the United States, forking over 50 percent more than other international visitors.

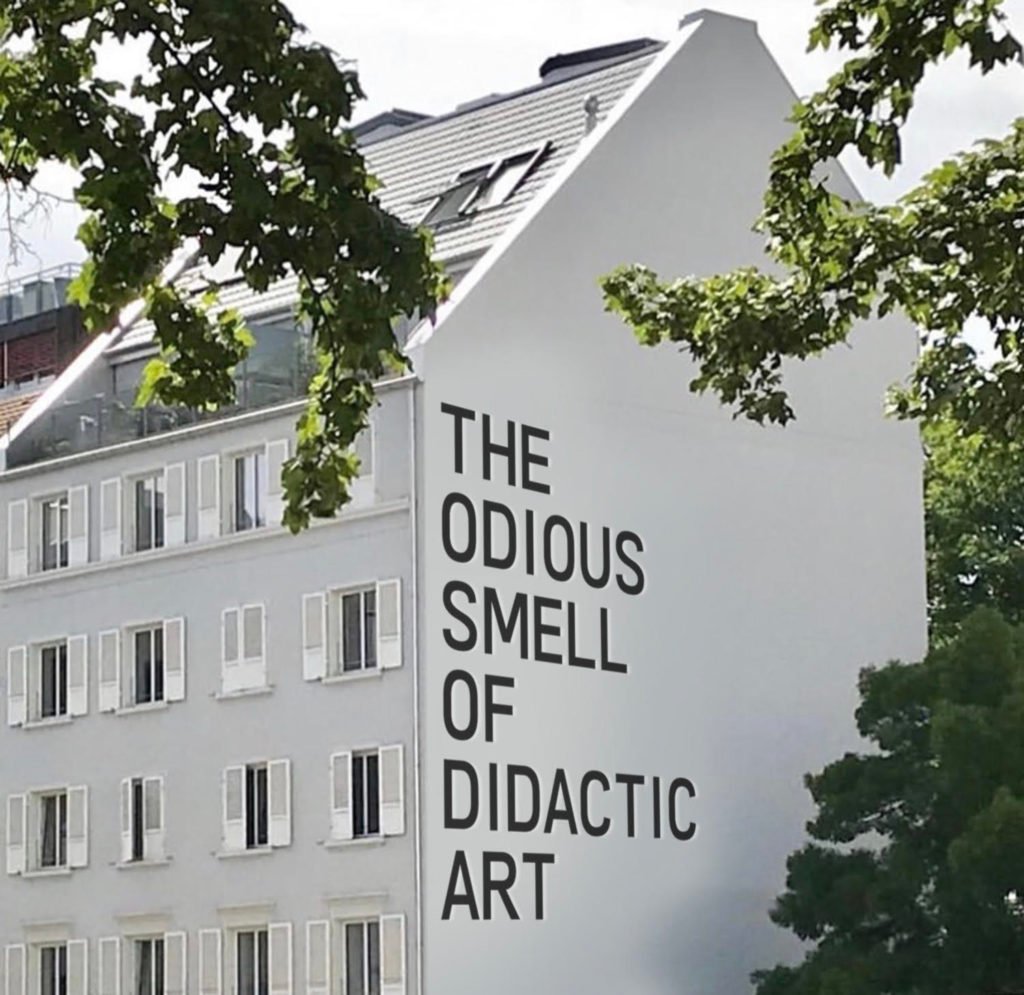

Gallerists hate when I reveal their prices—but there should be a constitutional, unassailable right to know, no? Though I kind of swore to many I wouldn’t, I can’t help myself. I steal (information) from the rich (art dealers) to serve up to you, dear readers, free of charge. I can only roll my eyes at the public text work by didactic market darling Rirkrit Tiravanija affixed to the side of a local Basel building that read: “The Odious Smell of Truth.” But I trade in truths that to me smell more like Chanel No. 5—but perhaps less so to others, like my friends at David Zwirner, Barbara Gladstone, Lévy Gorvy, and others.

My take on Rirkrit Tiravanija’s The Odious Smell of Truth. To me the truth smells delicious! Image collage courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Let’s begin with Zwirner. His Gerhard Richter crowd scene, widely reported to be sold for $20 million during the fair was, in actuality, presold at $16 million, I’m told. The seller was reputed to be an Italian collector, Massimo Valsecchi, who used to own a gallery, the proceeds of which probably went to the upkeep of his palazzo in Sicily where he exhibits his other Richters, Warhols, and Old Masters. (A Zwirner representative denied the work was sold for less than $20 million, but confirmed that it was consigned by Francesca and Massimo Valsecchi, specifically in order to “raise funds for the establishment of their public foundation and museum project, the Palazzo Butera.”)

The buyer of the Richter? All signs point to a Chinese collector who resides in the United States and who seen posing with Zwirner in front of the painting, both sporting Cheshire-cat grins. The gallery also had a set of Bruce Nauman hands for $1.75 million—much cheaper than Lévy Gorvy’s similar set for $2.7 million, both unsold last time I checked.

According to an auction-house friend, Zwirner’s Donald Judd stack on sale for $12.5 million previously sold for about $9 million two Basels back. In the Unlimited section of gargantuan works, the gallery exhibited the full set of 55 Félix González-Torres’s micro-sized cardboard puzzles, seen together for the first time, that was overwhelming—too much of a good thing, making it impossible to focus on any one work. I solved the riddle of how much the collection cost: $12 million in toto, unsold at the time of this writing. (González-Torres’s pair of mirrors in the booth, incidentally, was priced at $3.6 million). One prominent advisor pulled me aside in the Zwirner stand and said, sternly, and in no uncertain terms: “Don’t write about my clients!” I felt like I was on the set of The Sopranos.

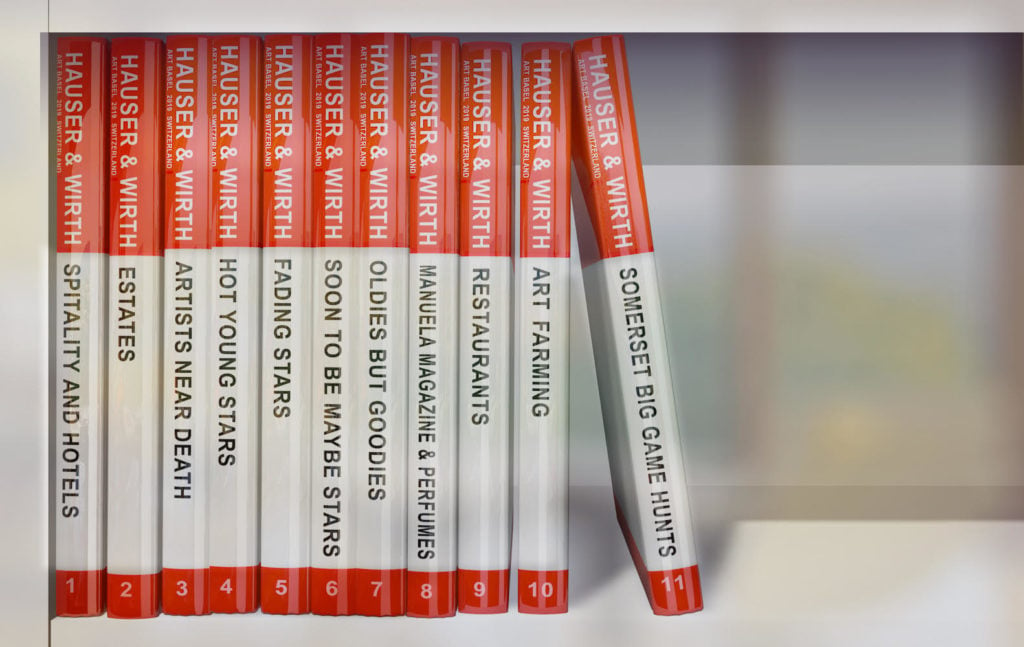

Gagosian Gallery(s)—there’s now, count ’em, 17 in all—sent out a 120-page PDF hawking its wares prior to the fair, but that paled in comparison next to the two-volume bound set of catalogues on offer from Hauser & Wirth. Outdoing Larry G on another front, the Swiss gallery conglomerate paid about $35 million to steal away John Chamberlain’s estate, and another $35 million (upfront) to coax David Hammons to play in the H&W sandpit in Los Angeles. It ain’t cheap to compete with the biggies in today’s art business.

The Hauser & Wirth behemoth marches on— where will it end? Image collage courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The new version of “fresh-to-market” is “renewed-resale,” like the Peter Doig that Geneva jewelry heavy Abdallah Chatila just bought at auction for $20 million, only to re-emerge on sale at the fair for $25 million. Then there is Thierry Gillier, the founder of trendy clothing label Zadig and Voltaire who flogs more of his “art collection” than his jeans—on this occasion a Christopher Wool that was back on the market at $6.5 million after being purchased second-hand from Simon Lee Gallery. Another Wool, previously auctioned at Phillips for $2.2 million, was last week on consignment from Jacques Seguin (the heart valve inventor, not Patrick the Prouvé market inventor) for $6 million. Both paintings went unsold.

Something you don’t hear much about are the art-fair reneges, which are far from uncommon. In this regard, there were at least a few pieces noted as sold during the commotion of Basel that were thereafter cancelled. (No doubt serious cases of buyer’s remorse set in.) When you say “I do” at a fair, unlike a wedding, there’s no binding contract. Not to overgeneralize, but the Chinese in particular are known for it, just after assiduously bargaining down the price and then haggling some more.

Koons’s giant shiny, blingy heart hung heavy at Gagosian, unsold at $14.5 million. Larry G’s Warhol dollar sign was available for $9 million, versus Christophe Van de Weghe’s similarly scaled work undercutting him at $8.9 million—though both failed to find a buyer. Joe Bradley’s latest modernist abstraction painting at Gagosian was sold for an astonishingly high $1.1 million, and a Mark Grotjahn for $5.5 million. Yes, though some (very) big ticket items remained unaccounted for, Larry G still managed to sell loads, as he always does. There is an undeniable, infectious energy in this booth, and a dynamic charisma to its mega-dealer, who will be sorely missed whenever he ultimately bows out—if that ever happens.

On that note, I’m told Gagosian has previously been in talks about selling the whole kit and caboodle to a non-art-associated private-equity firm in a deal that would presumably encompass the 24th Street gallery he owns outright and, I’d imagine, at least a chunk of his storied collection that is valued, more or less, at $1 billion. Why not? He’s got no heirs and I can’t imagine anyone in the business at present with anywhere near the wherewithal to match the legendary man himself—no matter how much he has attempted to plan for succession of late.

If I had anywhere near the dough, I’d buy his art stock and real estate, sell the building for condos (not the cartoon-on-canvas variety), auction some of the paintings to pay acquisition costs, and shut the galleries the next day. Which will happen anyway. A vulture fund for a vulture dealer, just watch.

When a museum such as Basel’s Beyeler shows an artist, it changes weather conditions—and so it was with its Rudolf Stingel show, which caused it to rain Stingels at the fair. The primary-market works seemed to sell quickly (i.e., before festivities kicked off), like the one for €2.2 million at Massimo De Carlo. Lévy Gorvy sold another for $1.8 million, which they marketed by stating the fabric used in the making of the work was Swiss-made (ugh), and Paula Cooper sold a realistic work for $2 million as well.

An installation view of “Rudolf Stingel” at Fondation Beyeler. Copyright Rudolf Stingel. Photo: Stefan Altenburger. Courtesy Foundation Beyeler and Gagosian.

At the Beyeler dinner for Stingel, the artist recounted a story of how he began his career as a dealer, selling fake Modiglianis at age 20; when he offered one to a Venice gallerist, the dealer replied that he knew where the original (real) painting was, saying: “Why don’t you go home and make art instead.” There you have it.

Los Angles’s Blum and Poe Gallery sold out before the completion of the first day, including paintings by Nara, Henry Taylor, Robert Colescott, up-and-coming Japanese star Tomoo Gokita, and four new Grotjahns that were hoovered up for near $1 million apiece before the onset. Flouting child-labor laws, the gallery has consistently employed Lux Blum—Tim’s son, with a name that could only emanate from LA—since he was 14 years old, with this being his fifth time manning the booth. I asked Lux for his take on the proceedings, to which he replied: “The funniest moment was when a young girl and her mother were taking photos way too close to our Nara, so my father asked them to move, and when she responded in German he told her—in the only German he knew—“Auf Wiedersehen! Die Welt ist schön!” Translation: “Goodbye! The world is beautiful!” I love Tim and Jeff, and not just because I will have a small project of my work in their Tokyo branch in spring 2020.

Last bit of breaking news! I solved the mystery of Steve Cohen’s missing caviar. When he had a tub sent to his room by a birthday well-wisher, it never made it, instead being mis-delivered to another Cohen staying at the same Trois Rois hotel. Frank Cohen (known as the Saatchi of the North of England, whose two kids work with Gagosian), taking advantage of the mix-up, proceeded to dig in. People incessantly bemoan art fairs, even me on occasion, but in truth I’m endlessly amused, entertained, and enriched by the onslaught. Now, however, I’m happy for a break—enjoy your summer.