We Poles are optimistic fatalists.

My gallery, Postmasters, opened in New York on a murky Saturday night on December 13, 1984—the anniversary of the post-Solidarity imposition of martial law in Poland, no less. In the gallery’s 35 years, my partner Tamás Banovich and I have weathered many storms and upheavals. We moved four times as gentrification pushed us back and forth across the city (from the East Village to Soho to Chelsea and, in 2013, to Tribeca). We survived the savings and loans crisis of the late ‘80s; 9/11; the Great Recession; Hurricane Sandy; and various smaller setbacks along the way. The global pandemic and subsequent economic collapse are, by far, the toughest challenges we’ve faced.

But I have hope for galleries like ours. In fact, I see a path forward from our current, painfully deficient online existence to one in which IRL galleries—and, specifically, small-to-midsize galleries—become vital again.

There will be a revolution. Art fairs will be dead for a long, long time, maybe forever. Gallery culture will be redefined. Survival will be based on innovation, adaptation, flexibility… and smallness. At the moment, oversized, shiny vessels control the spotlight. They have the resources and the PR apparatus. But in the end, it is little sailing boats that can best navigate choppy waters.

Wolfgang Staehle, Art Is Lost in This Town (1989). Photo courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

Let me explain.

The art ecosystem as we know it has not been a healthy, diverse place for a long time. Even before COVID-19, we had a bloated, predatorial, and over-industrialized art complex, rife with speculative collecting, surreal pricing, and risk-averse dealers with ears bigger than their eyes and brains trained to prize profit above all.

As the collector Alain Servais has tracked with his Twitter hashtag #GroworGo since 2012, there has been a systematic erosion of the lower levels of the art ecosystem, with many of the most vital, progressive galleries unable to stay in the race. This dynamic of destructive consolidation has been seen in other fields, too, but perhaps no more than in the contemporary art market.

The current virus may well be the equivalent of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Because sometimes, the system has to be destroyed in order to be liberated—and to make room for evolution.

The Opposite of “Size Matters”

The health and vitality of art is exclusively dependent on the bottom of the food chain. It relies first and foremost on the artists, who reflect on the world and the time we live in, and secondarily, on institutions, organizations, and galleries that have the passion and foresight to support them.

Tamás and I came to the US by choice as adults, and became Americans. But we never developed that acutely American “entrepreneurial gene,” instead searching for challenging and relevant art that the market has not yet swallowed whole. We look for new forms of creative expression that do not yet have the benefit—or the burden—of years, decades, or centuries of history behind them. We never wanted to anticipate where the market was headed. Rather, we aspired to challenge the market and, perhaps, to teach it. We like selling things and have, over the years, sold some rather impossible art, like websites by Rafaël Rozendaal and art literally stolen from others by Eva and Franco Mattes.

The author in a mask. Photo courtesy of Magda Sawon.

It has been a hard road that has been made possible by having a lean but muscular operation. We are a big small gallery or small big gallery (I forget which). Our core team is three people in New York and one in Rome. And I believe this type of efficient model is best equipped to emerge post-pandemic.

Here is the opposite side of the “size matters” argument:

Tamás used to sail competitively when growing up in Hungary. He sailed Finn dinghy, the smallest Olympic-class boat with a huge sail-to-hull ratio. One-man boats, Finns are beautiful: refined, deceptively simple, and extremely sensitive to wind and waves. Both sailor and boat must constantly adjust to changing conditions on the water. They are unforgiving and capsize easily, but can also recover fast. When compared to, say, cruise ships, the gas-guzzling floating entertainment centers with an obscene crew-to-passenger ratio, guess which vessel can maneuver and adapt better?

Back to the galleries.

Only the Small Survive

Better people have written beautifully about the need for art to be seen in real spaces to deliver a full spectrum of contemplative experience. But not all of these spaces will recover equally.

Galleries—which are by definition local, low-density environments—will be allowed to open their doors first. And people starving for non-virtual encounters will come. As theaters and other performing-art spaces have to reconsider their very structures to serve audiences safely, galleries will be able to reopen without too much change. (This is already happening in Shanghai, Berlin, and Vienna.)

Museums will follow. The logistics of re-opening them are far more complex, but manageable (as excellently laid out by András Szántó).

By requiring restrictions on travel and crowds, this pandemic has devastated the event industry. No sports games, no concerts, no Oktoberfest, and… no art fairs. As a result of the one-stop-shopping vacuum, collectors will inevitably visit galleries more. Of course, in an economy where most galleries have generated almost half their revenue from art fairs, there will be attrition as a vast segment of buy-to-sell collectors disappears.

Installation view of “saved by the web” (May/June 2017) at Postmasters, a three person show of Eva and Franco Mattes, Hasan Elahi and Lin Ke. Image courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

But I prefer to bet on the curiosity, vision, and connoisseurship of the collectors who stay in the game, and the new ones that will come along. The new paradigm—which will force people to engage intimately with art in a gallery setting—will favor them and the galleries that serve them. Artnet News columnist Tim Schneider has posed the theory that true collectors will return in force because they simply can’t help it. To keep the naval metaphors going, I am on board with this. True collectors are junkies in search of cultural value rather than a liquid asset. They will always look for new voices, not just the branded and easily consumable ones.

Perhaps, in the “new normal,” collectors will become more connected to their local scenes. Perhaps a shared experience of the world collapsing violently around us will favor content, which is good news for art that requires attention and the galleries that support it.

Even before we return to our physical galleries, the online migration of the past few months has shone a light on net and screen-based art (the only art, by the way, that is actually meant to be viewed online) and the (small and midsize) galleries like ours that have supported it. An incredible trove of historic and new material is out there, ready to take the spotlight, and ready to be collected—no shipping involved. We have championed media art (beginning with now historic “Can You Digit?” show in 1996) and used online platforms for documentation, dissemination, and sales for many years, which puts us at an advantage among galleries that have focused only on brick and mortar until now.

What’s Next

Just like in the world at large, the virus has exposed the gaps in wealth, connections, and access that already existed in the art market. We need more radical initiatives to save our industry, and to save art. Except for the newly announced and promising Platform LA and David Zwirner’s generous gestures (hosting selected young galleries online and, before the pandemic, hosting the displaced Volta), there is minimal cross-pollination in the gallery ecosystem. Top just takes from the bottom. Gives nothing.

Collaboration takes place among peers only, with small galleries banding together to share resources (Condo, NADA) and mega-galleries banding together to optimize business (see: Pagavella’s management of the Marron Collection).

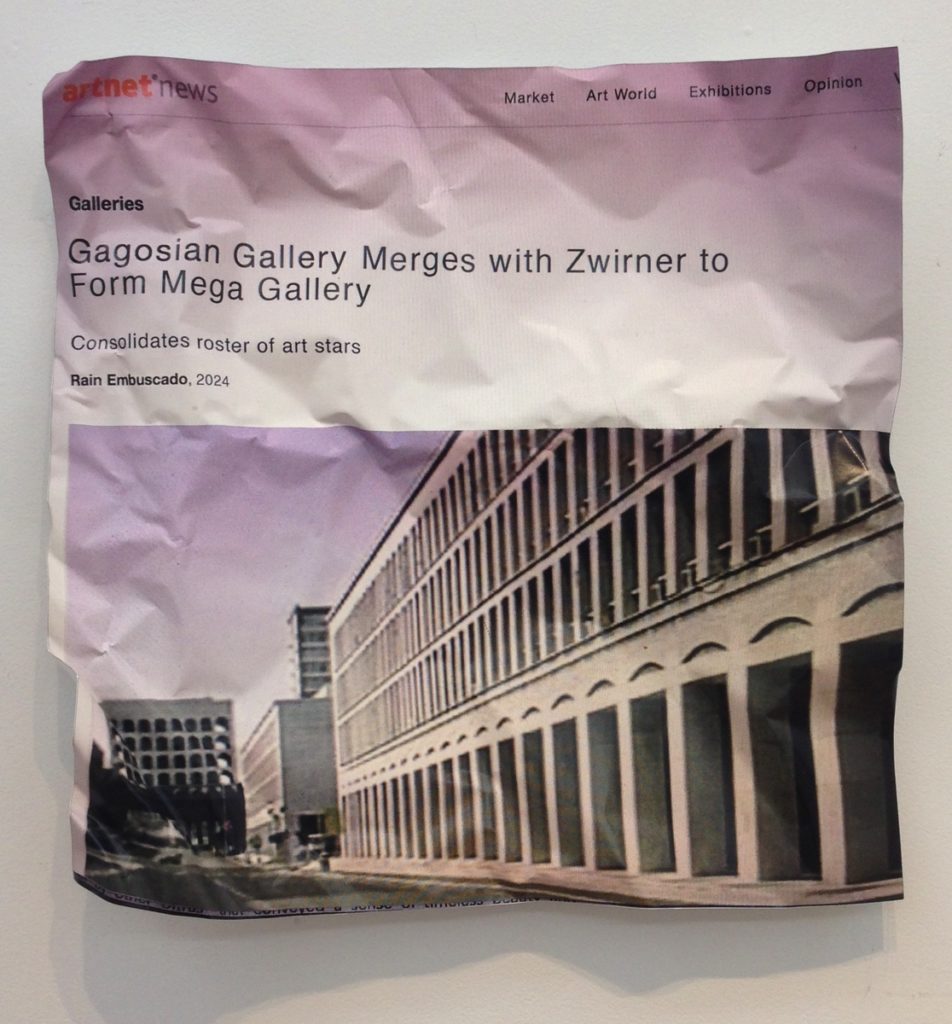

William Powhida’s Didactics (Gagosian and Zwirner) (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

But revolutions and change never come from the top. What we need is new, progressive ideas for both galleries and artists working separately and together rather than trying to plug the hole in a sinking ship. William Powhida, an artist we represent, recently came up with “Store-to-Own,” a novel way to distribute his work and get it out of storage. He offered select artworks to people to live with for free; they could purchase it at an increasing discount over the years or sell it and share the profit. It proved very successful. This kind of initiative offers no direct benefit to galleries—but it opens up a system that is in dire need of reinvention.

In the famous words of the infamous Donald Rumsfeld, “You go to the war with the army you have.” The post-Covid art world will be physically local and virtually global as the regional scenes (a domain of smaller galleries) gain relevance while “long-distance” art business continues and grows online.

Art is needed, and art will rise. To paraphrase Dylan: “Come gather Finn dinghies wherever you roam…”

All this may be naive and delusional. Along with many others, I may not be here in a few months, bankrupted and unable to continue. But this is the time. You know the David vs Goliath story. And you know how it ends. Take care, everybody.

Magda Sawon is the co-founder of Postmasters Gallery.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.