“You won’t hear too many extended sets about art history in a comedy show,” Hannah Gadsby says about three-quarters of the way through her now-viral Netflix stand-up special Nanette.

In the preceding 45 minutes, the art history student-turned-comedian has hit on high-culture topics including Vincent van Gogh’s mental illness (“He wasn’t born ahead of his time—he just couldn’t network”), the historical depiction of women (“Art history taught me that, historically, women didn’t have time to think thoughts—too busy napping naked alone in the forest”), and Picasso’s misogyny (“Aren’t we grateful that we live in a post-Cubism world? Isn’t that the first thing we write in our gratitude journals?”).

The Tasmanian comedian’s hour-long special has been widely praised, in large part because it actually becomes quite un-funny about halfway through. That’s when Gadsby sets out to explain why she is quitting comedy: Because punchlines are incapable of providing an honest, full accounting of an individual’s story.

Gadsby is interested in deconstructing the narratives that make our heroes—including artists and comedians—into hollow archetypes, from the starving, depressed creative to the tortured, virile genius. It feels refreshing, and necessary. And it’s a lesson that many museums, which have struggled to figure out how to contend with #metoo-era revelations about male artists’ bad behavior, would do well to take to heart.

Gadsby’s language is quite a bit more colorful than that of traditional art historians. To describe the depiction of women in the Renaissance, she quips: “If you go into the galleries, you’ll see that if a woman isn’t sporting a corset and/or a hymen, she just loses all structure.”

Nevertheless, her unexpected art criticism has managed to hit on a zeitgeist that the art world at large hasn’t quite yet figured out how to address or articulate. We’re still not sure what to do with our heroes once they are proven to be less than palatable.

Dismantling Van Gogh

Gadsby’s take on Van Gogh offers a good warm up. She recounts an exchange with a fan who suggested she should not take antidepressants because, as an artist, she shouldn’t elect to dull her emotions. “He said, ‘If Vincent van Gogh had taken medication, we wouldn’t have had the Sunflowers,’” she recalls.

Gadsby then proceeds to dismantle his claim, noting that Van Gogh painted several portraits of psychiatrists who were treating him. In Portrait of Dr. Gachet, the doctor is holding a foxglove, the plant from which the medication Van Gogh took for epilepsy derives.

Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890). Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

“And that derivative of the foxglove plant, if you overdose a bit, you know what happens?” she asks, winding herself up, almost spitting out each word. “You can experience the color yellow a little too intensely. So perhaps we have the Sunflowers precisely because Van Gogh medicated.”

In the second half of her set, Gadsby revisits jokes and stories she told in the first half—but instead of telling them just for laughs, she considers them a bit more holistically. “You learn from the part of the story you focus on,” she says. “Take Vincent. The way we tell his story, it’s no good. We reduce him to a tale of rags to riches.”

Of course, that’s not really how it worked. By the time Van Gogh was celebrated by the art establishment, he was dead. Here’s how Gadsby puts it:

People believe that Van Gogh was just this misunderstood genius, born ahead of his time. What a load of shit. Nobody is born ahead of their time! It’s impossible. Maybe premie babies, but they catch up. Artists don’t invent zeitgeists, they respond to it….

[Van Gogh] was not ahead of his time. He was a post-Impressionist painter painting at the peak of post-Impressionism.

He had unstable energy, people crossed the street to avoid him. That’s why he didn’t sell any more than one painting in his lifetime.

This romanticizing of mental illness is ridiculous. It is not a ticket to genius. It’s a ticket to nowhere.

The mentally unstable creative is not the only heroic archetype Gadsby is out to deconstruct. In fact, it merely serves as a warm up to her most bracing art-historical analysis.

Picasso on the Chopping Block

In January, at the height of the #metoo movement, Jock Reynolds, the director of the Yale University Art Gallery, articulated a question that many museum directors were asking themselves at the time: How far should this re-evaluation of the work of abusive men go?

“At some point you have to ask yourself, is the art going to stand alone as something that needs to be seen?” Reynolds told the New York Times. “Pablo Picasso was one of the worst offenders of the 20th century in terms of his history with women. Are we going to take his work out of the galleries?”

In the context of that Times article, this question was almost rhetorical. Modernism is built on the back of Picasso. You can’t put that particular cat back in the frame.

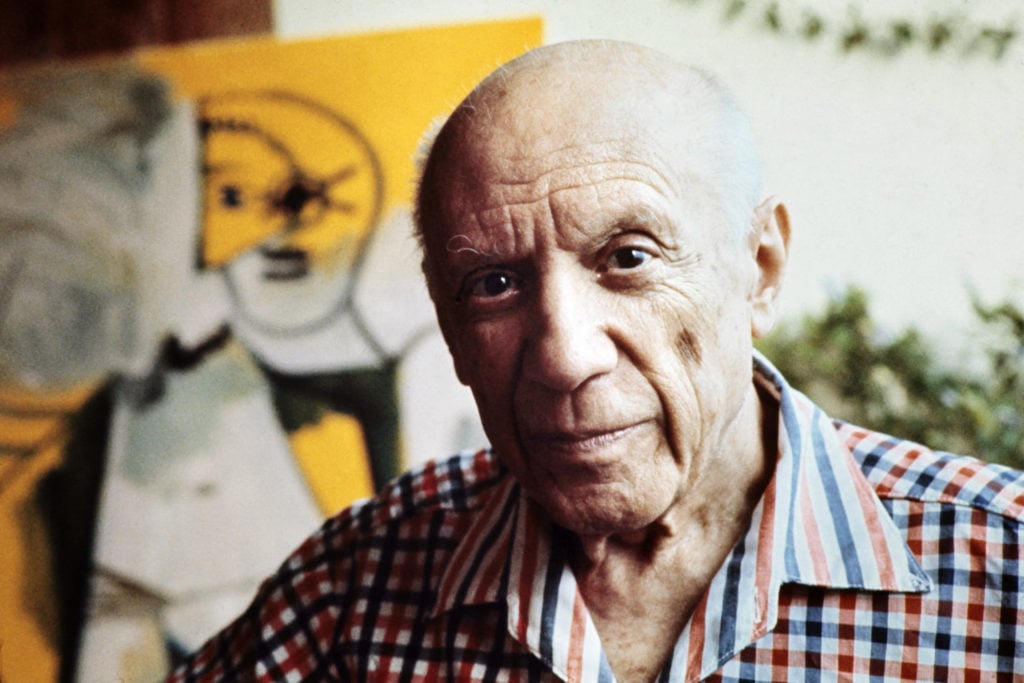

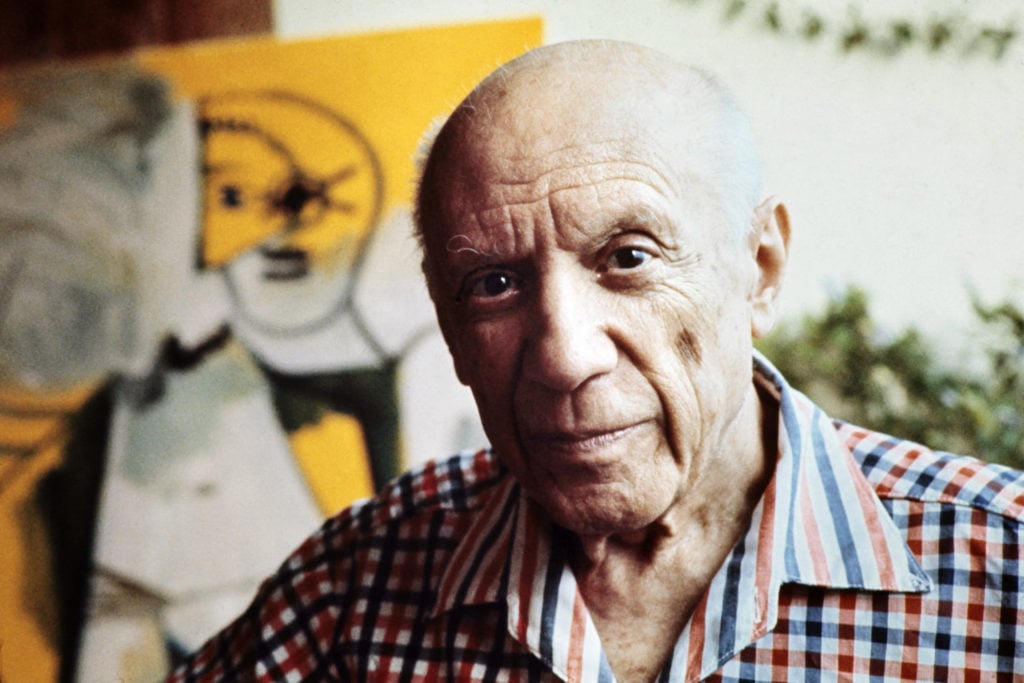

Pablo Picasso in Mougins, France in October 1971. (RALPH GATTI/AFP/Getty Images)

But this is exactly what Gadsby is asking us to do: radically re-assess the most famous artist of the 20th century by contemporary moral standards. For me, this moment in the special marks a crescendo of feeling and a shift in tone—a moment when Gadsby wants to drive home her point much more than she wants to make you laugh, and comedy turns the corner into biting critique. Here is a slightly shortened version:

I hate Picasso. and you can’t make me like him. I know I should be more generous about him too, because he suffered a mental illness. But nobody knows that, because it doesn’t fit with his mythology. Picasso is sold to us as this passionate, tormented, genius, man-ball-sack. But Picasso suffered the mental illness…of misogyny.

Don’t believe me? He said, “Each time I leave a woman, I should burn her. Destroy the woman, you destroy the past she represents.” Cool guy. The greatest artist of the 20th century. Picasso fucked an underage girl. That’s it for me, not interested.

But Cubism! He made it! Marie-Thérèse Walter, she was 17 when they met: underage. Picasso, he was 42, at the height of his career. Does it matter? It actually does matter. But as Picasso said, “It was perfect—I was in my prime, she was in her prime.” I probably read that when I was 17. Do you know how grim that was?

(A brief fact check is in order: According to John Richardson’s famed biography of Picasso, the artist was actually 45, not 42, when he met Marie-Thérèse. I also could not independently confirm the exact language of the Picasso quote. Gadsby is right, however, about Marie-Thérèse being 17.)

Cubism is important. Picasso freed us from the slavery of having to reproduce three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface. Picasso said, “You can have all the perspectives at once—from above, from below. All the perspectives at once!” What a hero. But tell me, are any of those perspectives a woman’s? Well, then, I’m not interested.

“Separate the man from the art. You gotta learn to separate the man from the art. The art is important, not the artist.” OK, let’s give it a go. How about you take Picasso’s name off his little paintings there and see how much his doodles are worth at auction? Nobody owns a circular lego nude. They own a Picasso.

A Closer Look

Is Gadsby right about Picasso? It’s worth noting that the incident she cites is not even the most disturbing anecdote available about Picasso’s treatment of women.

Indeed, he once extinguished his cigarette on the cheek of Francoise Gilot, according to her own account. And as Catherine Wagley recounts in a recent article for Good magazine, Picasso once took Caroline Blackwood, the first wife of Lucian Freud, onto his roof and lunged at her. Blackwood describes the encounter, and her own terror, in the kind of lurid detail that one can now no longer help but associate with the many exposes on Harvey Weinstein.

“All I felt was fear,” [Blackwood] recalled years later. “I kept saying, ‘Go down the stairs, go down.’ He said, ‘No, no, we are together above the roofs of Paris.’ It was so absurd, and to me, Picasso was just as old as the hills, an old letch, genius or no…. And to think how many people he had up there.”

As Jock Reynolds noted, these revelations are not new—they’re widely known elements of Picasso’s character. We just think about them differently now that we live in a society where they might be discussed in a Netflix special. Notably, stories about Bill Cosby’s abuse were also widely known, but rarely acknowledged until a pointed comedy set ignited a reckoning.

Pablo Picasso and his wife Jacqueline Roque at their home in Vallauris on October 22, 1961. (ANDRE VILLERS/AFP/Getty Images)

In the case of Picasso, if these anecdotes were told, they were often told in service of the romantic narrative of an obsessive, passionate, difficult artist whose tumultuous relationships with women were the necessary match to light his creative fire.

Even Marie-Thérèse seemed to view the dynamic this way. In a 1974 interview, one year after Picasso’s death and three years before she herself died by suicide, she would say: “That’s the way it is with him. He violates the woman first, then afterwards we work.”

Picasso expert John Richardson—whose four-volume biography is widely considered the gold standard of artist biographies—has done much to promote this narrative. “That whole business of the submissiveness of his women made for great art,” he said in a 2010 interview. He described several of Picasso’s partners’ willingness to sacrifice themselves on the altar of his art as “noble and wonderful.”

Gadsby, it is safe to say, would not agree. Toward the end of her set, she revisits Picasso.

I want my story heard because, ironically, I believe Picasso was right. I believe we could create a better world if we learned to see the world from all different perspectives—as many perspectives as we possibly could. Because diversity is strength. Difference is a teacher. Fear difference, you learn nothing.

Picasso’s mistake was his arrogance. He assumed he could represent all of the perspectives. And our mistake was to invalidate the perspective of a 17-year-old girl because we believed her potential would never equal his.

Hindsight is a gift. Stop wasting my time.

A 17-year-old girl is never in her prime. Ever. I am in my prime. Would you test your strength out on me?

A Netflix comedy special is not going to compel museums to throw out their Picassos. Nor should they! You can’t tell the story of 20th-century art without him. But Gadsby’s set does contain a challenge that museums and art historians would do well to take to heart: As she says, hindsight is a gift.

Hannah Gadsby. Still from Nanette on Netflix.

In other words, it’s not intellectually dishonest or unjust to reconsider artists in the context of contemporary moral standards. In fact, it’s more honest.

Although glossing over, whitewashing, or shoe-horning stories of Picasso’s abuse into a comfortable narrative about passionate genius may be useful to maintain his market value and his bankability as a tourist attraction, it also does everyone a disservice. It fuels the idea that artists are supposed to be moral exemplars and heroes—and then, when we are confronted with evidence that they are not, we don’t know what to do. The house of cards comes crashing down.

What happens when the story of Picasso isn’t entirely inspiring anymore? This is a question museums and mythmakers likely do not want to answer. A lot of art-world infrastructure depends on the notion that he, and other artists like him, are untouchable icons. It is unlikely, for example, that the Museum of Modern Art would have drawn as many crowds to its Picasso sculpture exhibition if he were presented not just as a man with “a lifelong commitment to constant reinvention,” but also as an abusive, terrible person.

I do not think, as Gadsby suggests, that we can do away with Picasso. We can’t change the fact that predators, liars, abusers—and even murderers, in the case of Caravaggio—are also some of our most influential artists.

But I do think we can understand Picasso’s contributions better if we can hold these two seemingly incompatible truths in our minds at once. It’s not as uplifting as a straightforward tale about a visionary creative whose flaws were only in service to its genius. But it is more honest—and it might even help us understand the evolution of our own culture, and how we got to where we are today, a lot better.

As Gadsby says in her special, “Artists are not these incredible mythical creatures that exist outside of the world. Artists have always been very much a part of the world and firmly attached to power.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.